| MOHENJO - DARO

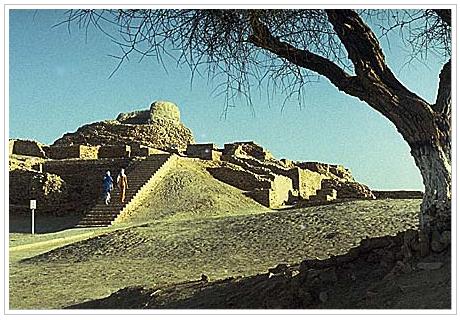

Mohenjo-daro Mohenjo-daro meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men' is an archaeological site in the province of Sindh, Pakistan. Built around 2500 BCE, it was one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation, and one of the world's earliest major cities, contemporaneous with the civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Minoan Crete, and Norte Chico. Mohenjo-daro was abandoned in the 19th century BCE as the Indus Valley Civilization declined, and the site was not rediscovered until the 1920s. Significant excavation has since been conducted at the site of the city, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980. The site is currently threatened by erosion and improper restoration.

Etymology

:

Mohenjo-daro, the modern name for the site, has been variously interpreted as "Mound of the Dead Men" in Sindhi, and as "Mound of Mohan" (where Mohan is Krishna).

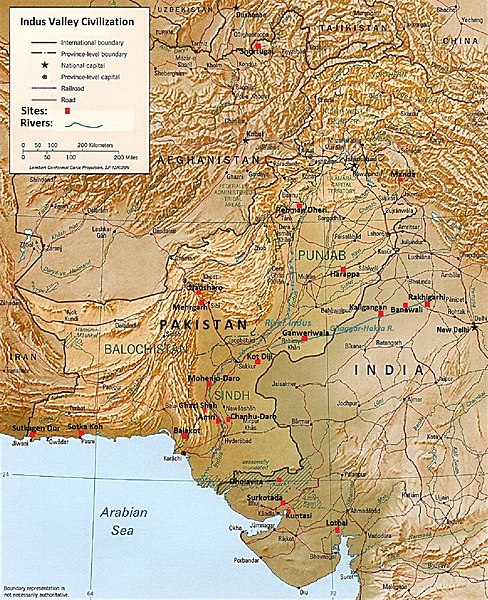

Location :

Map showing the major sites and theorised extent of the Indus Valley Civilisation, including the location of the Mohenjo-daro site Mohenjo-daro is located west of the Indus River in Larkan District, Sindh, Pakistan, in a central position between the Indus River and the Ghaggar-Hakra River. It is situated on a Pleistocene ridge in the middle of the flood plain of the Indus River Valley, around 28 kilometres (17 mi) from the town of Larkana. The ridge was prominent during the time of the Indus Valley Civilization, allowing the city to stand above the surrounding flood, but subsequent flooding has since buried most of the ridge in silt deposits. The Indus still flows east of the site, but the Ghaggar-Hakra riverbed on the western side is now dry.

Historical

context :

Rediscovery and excavation :

The ruins of the city remained undocumented for around 3,700 years until R. D. Banerji, an officer of the Archaeological Survey of India, visited the site in 1919–20 identifying what he thought to be a Buddhist stupa (150–500 CE) known to be there and finding a flint scraper which convinced him of the site's antiquity. This led to large-scale excavations of Mohenjo-daro led by Kashinath Narayan Dikshit in 1924–25, and John Marshall in 1925–26. In the 1930s major excavations were conducted at the site under the leadership of Marshall, D. K. Dikshitar and Ernest Mackay. Further excavations were carried out in 1945 by Mortimer Wheeler and his trainee, Ahmad Hasan Dani. The last major series of excavations were conducted in 1964 and 1965 by George F. Dales. After 1965 excavations were banned due to weathering damage to the exposed structures, and the only projects allowed at the site since have been salvage excavations, surface surveys, and conservation projects. In the 1980s, German and Italian survey groups led by Michael Jansen and Maurizio Tosi used less invasive archeological techniques, such as architectural documentation, surface surveys, and localized probing, to gather further information about Mohenjo-daro. A dry core drilling conducted in 2015 by Pakistan's National Fund for Mohenjo-daro revealed that the site is larger than the unearthed area.

Architecture and urban infrastructure :

Regularity of streets and buildings suggests the influence of ancient urban planning in Mohenjo-daro's construction

View of the site's Great Bath, showing the surrounding urban layout Mohenjo-daro has a planned layout with rectilinear buildings arranged on a grid plan. Most were built of fired and mortared brick; some incorporated sun-dried mud-brick and wooden superstructures. The covered area of Mohenjo-daro is estimated at 300 hectares. The Oxford Handbook of Cities in World History offers a "weak" estimate of a peak population of around 40,000.

The sheer size of the city, and its provision of public buildings and facilities, suggests a high level of social organization. The city is divided into two parts, the so-called Citadel and the Lower City. The Citadel – a mud-brick mound around 12 metres (39 ft) high – is known to have supported public baths, a large residential structure designed to house about 5,000 citizens, and two large assembly halls. The city had a central marketplace, with a large central well. Individual households or groups of households obtained their water from smaller wells. Waste water was channeled to covered drains that lined the major streets. Some houses, presumably those of more prestigious inhabitants, include rooms that appear to have been set aside for bathing, and one building had an underground furnace (known as a hypocaust), possibly for heated bathing. Most houses had inner courtyards, with doors that opened onto side-lanes. Some buildings had two stories.[citation needed]

Major buildings :

The Great Bath In 1950, Sir Mortimer Wheeler identified one large building in Mohenjo-daro as a "Great Granary". Certain wall-divisions in its massive wooden superstructure appeared to be grain storage-bays, complete with air-ducts to dry the grain. According to Wheeler, carts would have brought grain from the countryside and unloaded them directly into the bays. However, Jonathan Mark Kenoyer noted the complete lack of evidence for grain at the "granary", which, he argued, might therefore be better termed a "Great Hall" of uncertain function. Close to the "Great Granary" is a large and elaborate public bath, sometimes called the Great Bath. From a colonnaded courtyard, steps lead down to the brick-built pool, which was waterproofed by a lining of bitumen. The pool measures 12 metres (39 ft) long, 7 metres (23 ft) wide and 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) deep. It may have been used for religious purification. Other large buildings include a "Pillared Hall", thought to be an assembly hall of some kind, and the so-called "College Hall", a complex of buildings comprising 78 rooms, thought to have been a priestly residence.[citation needed]

Fortifications :

Excavation of the city revealed very tall wells (left), which it seems were continually built up as flooding and rebuilding raised the elevation of street level Mohenjo-daro had no series of city walls, but was fortified with guard towers to the west of the main settlement, and defensive fortifications to the south. Considering these fortifications and the structure of other major Indus valley cities like Harappa, it is postulated that Mohenjo-daro was an administrative center. Both Harappa and Mohenjo-daro share relatively the same architectural layout, and were generally not heavily fortified like other Indus Valley sites. It is obvious from the identical city layouts of all Indus sites that there was some kind of political or administrative centrality, but the extent and functioning of an administrative center remains unclear.

Water

supply and wells :

Flooding

and rebuilding :

Notable artefacts :

Boat with direction finding birds to find land. Model of Mohenjo-Daro seal, 2500-1750 BCE Numerous objects found in excavation include seated and standing figures, copper and stone tools, carved seals, balance-scales and weights, gold and jasper jewellery, and children's toys. Many bronze and copper pieces, such as figurines and bowls, have been recovered from the site, showing that the inhabitants of Mohenjo-daro understood how to utilize the lost wax technique. The furnaces found at the site are believed to have been used for copperworks and melting the metals as opposed to smelting. There even seems to be an entire section of the city dedicated to shell-working, located in the northeastern part of the site. Some of the most prominent copperworks recovered from the site are the copper tablets which have examples of the untranslated Indus script and iconography. While the script has not been cracked yet, many of the images on the tablets match another tablet and both hold the same caption in the Indus language, with the example given showing three tablets with the image of a mountain goat and the inscription on the back reading the same letters for the three tablets. Pottery and terracotta sherds have been recovered from the site, with many of the pots having deposits of ash in them, leading archeologists to believe they were either used to hold the ashes of a person or as a way to warm up a home located in the site. These heaters, or braziers, were ways to heat the house while also being able to be utilized in a manner of cooking or straining, while others solely believe they were used for heating. Many important objects from Mohenjo-daro are conserved at the National Museum of India in Delhi and the National Museum of Pakistan in Karachi. In 1939, a representative collection of artefacts excavated at the site was transferred to the British Museum by the Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India.

Mother

Goddess Idol :

Picture of original Goddess

"The Dancing Girl" (replica) A bronze statuette dubbed the "Dancing Girl", 10.5 centimetres (4.1 in) high and about 4,500 years old, was found in 'HR area' of Mohenjo-daro in 1926; it is now in the National Museum, New Delhi. In 1973, British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler described the item as his favorite statuette:

"She's about fifteen years old I should think, not more, but she stands there with bangles all the way up her arm and nothing else on. A girl perfectly, for the moment, perfectly confident of herself and the world. There's nothing like her, I think, in the world."

John Marshall, another archeologist at Mohenjo-daro, described the figure as "a young girl, her hand on her hip in a half-impudent posture, and legs slightly forward as she beats time to the music with her legs and feet." The archaeologist Gregory Possehl said of the statuette, "We may not be certain that she was a dancer, but she was good at what she did and she knew it". The statue led to two important discoveries about the civilization: first, that they knew metal blending, casting and other sophisticated methods of working with ore, and secondly that entertainment, especially dance, was part of the culture.

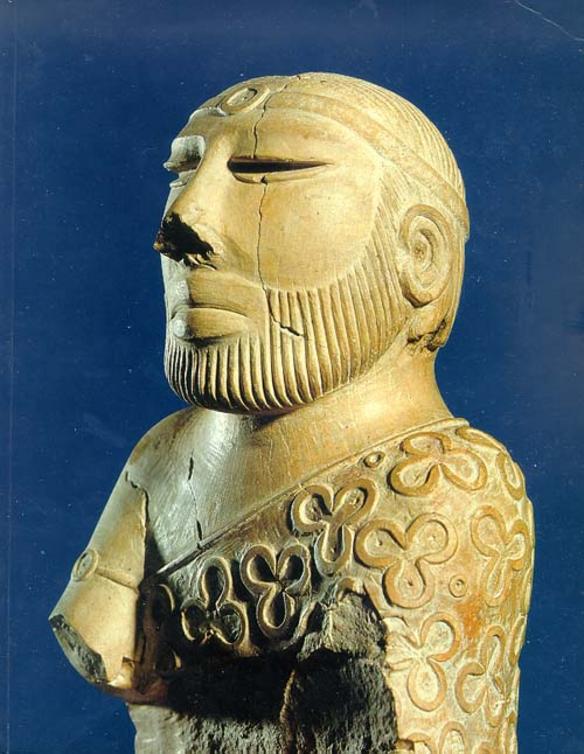

Priest-King :

"The Priest-King", a seated stone sculpture at the National Museum, Karachi In 1927, a seated male soapstone figure was found in a building with unusually ornamental brickwork and a wall-niche. Though there is no evidence that priests or monarchs ruled Mohenjo-daro, archaeologists dubbed this dignified figure a "Priest-King." The sculpture is 17.5 centimetres (6.9 in) tall, and shows a neatly bearded man with pierced earlobes and a fillet around his head, possibly all that is left of a once-elaborate hairstyle or head-dress; his hair is combed back. He wears an armband, and a cloak with drilled trefoil, single circle and double circle motifs, which show traces of red. His eyes might have originally been inlaid.

The Pashupati seal :

Pashupati seal A seal discovered at the site bears the image of a seated, cross-legged and possibly ithyphallic figure surrounded by animals. The figure has been interpreted by some scholars as a yogi, and by others as a three-headed "proto-Shiv" as "Lord of Animals".

Seven-stranded

necklace :

Conservation

and current state :

Preservation work for Mohenjo-daro was suspended in December 1996 after funding from the Pakistani government and international organizations stopped. Site conservation work resumed in April 1997, using funds made available by the UNESCO. The 20-year funding plan provided $10 million to protect the site and standing structures from flooding. In 2011, responsibility for the preservation of the site was transferred to the government of Sindh.

Currently the site is threatened by groundwater salinity and improper restoration. Many walls have already collapsed, while others are crumbling from the ground up. In 2012, Pakistani archaeologists warned that, without improved conservation measures, the site could disappear by 2030.

Surviving structures at Mohenjo-daro 2014

Sindh Festival :

Climate

:

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)