| SUMERIAN RELIGION

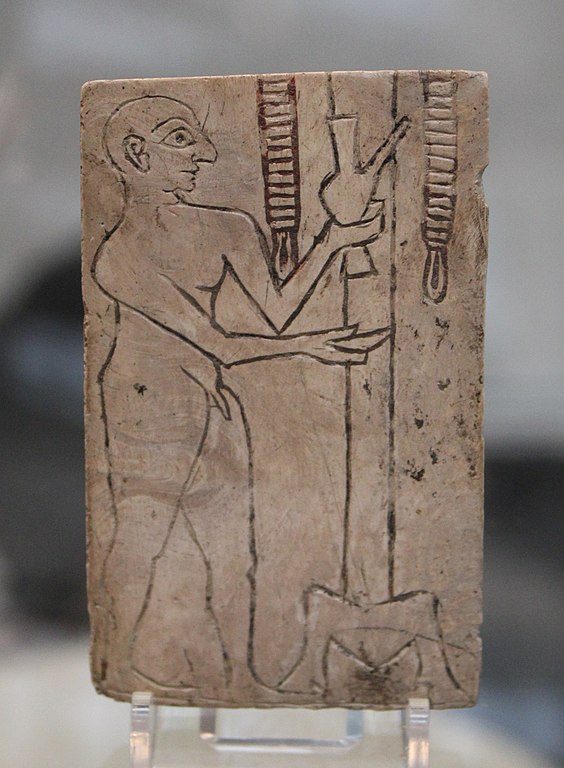

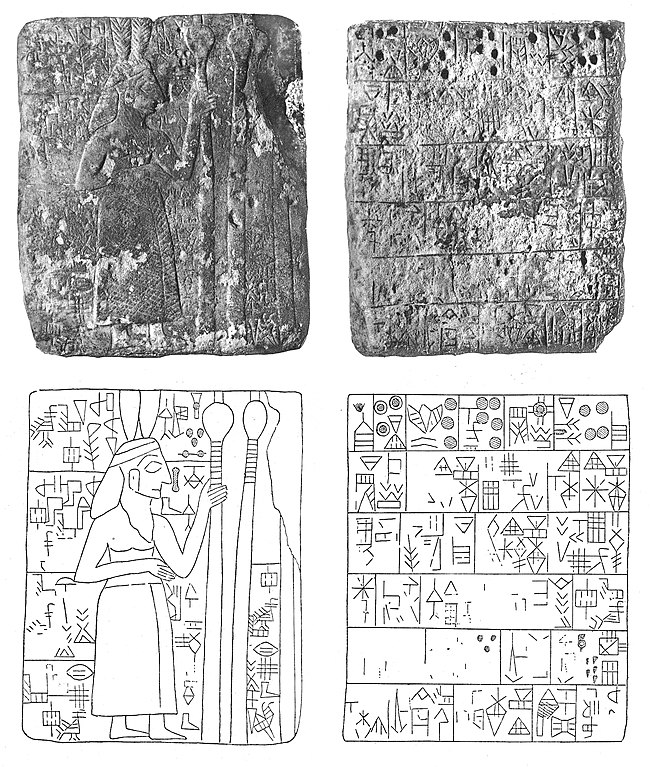

Wall plaque showing libations by devotees and a naked priest, to a seated god and a temple. Ur, 2500 BCE Sumerian religion was the religion practiced and adhered to by the people of Sumer, the first literate civilization of ancient Mesopotamia. The Sumerians regarded their divinities as responsible for all matters pertaining to the natural and social orders.

Before the beginning of kingship in Sumer, the city-states were effectively ruled by theocratic priests and religious officials. Later, this role was supplanted by kings, but priests continued to exert great influence on Sumerian society. In early times, Sumerian temples were simple, one-room structures, sometimes built on elevated platforms. Towards the end of Sumerian civilization, these temples developed into ziggurats—tall, pyramidal structures with sanctuaries at the tops.

The Sumerians believed that the universe had come into being through a series of cosmic births. First, Nammu, the primeval waters, gave birth to Ki (the earth) and An (the sky), who mated together and produced a son named Enlil. Enlil separated heaven from earth and claimed the earth as his domain. Humans were believed to have been created by Enki, the son of Nammu and An. Heaven was reserved exclusively for deities and, upon their deaths, all mortals' spirits, regardless of their behavior while alive, were believed to go to Kur, a cold, dark cavern deep beneath the earth, which was ruled by the goddess Ereshkigal and where the only food available was dry dust. In later times, Ereshkigal was believed to rule alongside her husband Nergal, the god of death.

The major deities in the Sumerian pantheon included An, the god of the heavens, Enlil, the god of wind and storm, Enki, the god of water and human culture, Ninhursag, the goddess of fertility and the earth, Utu, the god of the sun and justice, and his father Nanna, the god of the moon. During the Akkadian Period and afterward, Inanna, the goddess of sex, beauty, and warfare, was widely venerated across Sumer and appeared in many myths, including the famous story of her descent into the Underworld.

Sumerian religion heavily influenced the religious beliefs of later Mesopotamian peoples; elements of it are retained in the mythologies and religions of the Hurrians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and other Middle Eastern culture groups. Scholars of comparative mythology have noticed many parallels between the stories of the ancient Sumerians and those recorded later in the early parts of the Hebrew Bible.

Worship

:

Evolution

of the word "Temple" (Sumerian: "É")

in cuneiform, from a 2500 BCE relief in Ur, to Assyrian cuneiform

circa 600 BCE.

Architecture :

In the Sumerian city-states, temple complexes originally were small, elevated one-room structures. In the early dynastic period, temples developed raised terraces and multiple rooms. Toward the end of the Sumerian civilization, ziggurats became the preferred temple structure for Mesopotamian religious centers. Temples served as cultural, religious, and political headquarters until approximately 2500 BC, with the rise of military kings known as Lu-gals (“man” + “big”) after which time the political and military leadership was often housed in separate "palace" complexes.

Priesthood :

Statuette of a Sumerian worshipper from the Early Dynastic Period, ca. 2800-2300 BC Until the advent of the lugals, Sumerian city states were under a virtually theocratic government controlled by various En or Ensí, who served as the high priests of the cults of the city gods. (Their female equivalents were known as Nin.) Priests were responsible for continuing the cultural and religious traditions of their city-state, and were viewed as mediators between humans and the cosmic and terrestrial forces. The priesthood resided full-time in temple complexes, and administered matters of state including the large irrigation processes necessary for the civilization's survival.

Ceremony

:

Cosmology

:

Creation

story :

Carved figure with feathers. The king-priest, wearing a net skirt

and a hat with leaves or feathers, stands before the door of a temple,

symbolized by two great maces. The inscription mentions the god

Ningirsu. Early Dynastic Period, circa 2700 BCE.

Heaven

:

Afterlife :

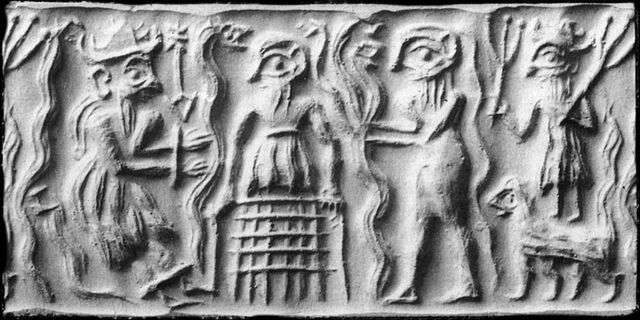

Ancient Sumerian cylinder seal impression showing the god Dumuzid being tortured in the Underworld by galla demons

Devotional scene, with Temple The Sumerian afterlife was a dark, dreary cavern located deep below the ground, where inhabitants were believed to continue "a shadowy version of life on earth". This bleak domain was known as Kur, and was believed to be ruled by the goddess Ereshkigal. All souls went to the same afterlife, and a person's actions during life had no effect on how the person would be treated in the world to come.

The souls in Kur were believed to eat nothing but dry dust and family members of the deceased would ritually pour libations into the dead person's grave through a clay pipe, thereby allowing the dead to drink. Nonetheless, there are assumptions according to which treasures in wealthy graves had been intended as offerings for Utu and the Anunnaki, so that the deceased would receive special favors in the underworld. During the Third Dynasty of Ur, it was believed that a person's treatment in the afterlife depended on how he or she was buried; those that had been given sumptuous burials would be treated well, but those who had been given poor burials would fare poorly, and were believed to haunt the living.

The entrance to Kur was believed to be located in the Zagros mountains in the far east. It had seven gates, through which a soul needed to pass. The god Neti was the gatekeeper. Ereshkigal's sukkal, or messenger, was the god Namtar. Galla were a class of demons that were believed to reside in the underworld; their primary purpose appears to have been to drag unfortunate mortals back to Kur. They are frequently referenced in magical texts, and some texts describe them as being seven in number. Several extant poems describe the galla dragging the god Dumuzid into the underworld. The later Mesopotamians knew this underworld by its East Semitic name: Irkalla. During the Akkadian Period, Ereshkigal's role as the ruler of the underworld was assigned to Nergal, the god of death. The Akkadians attempted to harmonize this dual rulership of the underworld by making Nergal Ereshkigal's husband.

Pantheon

:

The dragon Mušhuššu on a vase of Gudea, circa 2100 BCE It is generally agreed that Sumerian civilization began at some point between c. 4500 and 4000 BC, but the earliest historical records only date to around 2900 BC. The Sumerians originally practiced a polytheistic religion, with anthropomorphic deities representing cosmic and terrestrial forces in their world. The earliest Sumerian literature of the third millennium BC identifies four primary deities: An, Enlil, Ninhursag, and Enki. These early deities were believed to occasionally behave mischievously towards each other, but were generally viewed as being involved in co-operative creative ordering.

During the middle of the third millennium BC, Sumerian society became more urbanized. As a result of this, Sumerian deities began to lose their original associations with nature and became the patrons of various cities. Each Sumerian city-state had its own specific patron deity, who was believed to protect the city and defend its interests. Lists of large numbers of Sumerian deities have been found. Their order of importance and the relationships between the deities has been examined during the study of cuneiform tablets.

During the late 2000s BC, the Sumerians were conquered by the Akkadians. The Akkadians syncretized their own gods with the Sumerian ones, causing Sumerian religion to take on a Semitic coloration. Male deities became dominant and the gods completely lost their original associations with natural phenomena. People began to view the gods as living in a feudal society with class structure. Powerful deities such as Enki and Inanna became seen as receiving their power from the chief god Enlil.

Major deities :

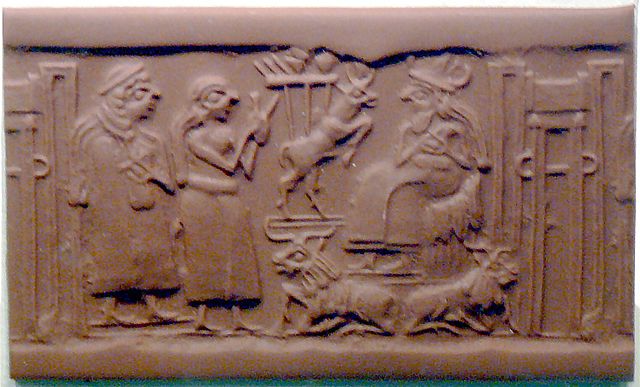

Akkadian cylinder seal from sometime around 2300 BC or thereabouts depicting the deities Inanna, Utu, Enki, and Isimud The majority of Sumerian deities belonged to a classification called the Anunna (“[offspring] of An”), whereas seven deities, including Enlil and Inanna, belonged to a group of “underworld judges" known as the Anunnaki (“[offspring] of An” + Ki). During the Third Dynasty of Ur, the Sumerian pantheon was said to include sixty times sixty (3600) deities.

Enlil was the god of air, wind, and storm. He was also the chief god of the Sumerian pantheon and the patron deity of the city of Nippur. His primary consort was Ninlil, the goddess of the south wind, who was one of the matron deities of Nippur and was believed to reside in the same temple as Enlil. Ninurta was the son of Enlil and Ninlil. He was worshipped as the god of war, agriculture, and one of the Sumerian wind gods. He was the patron deity of Girsu and one of the patron deities of Lagash.

Enki was god of freshwater, male fertility, and knowledge. His most important cult center was the E-abzu temple in the city of Eridu. He was the patron and creator of humanity and the sponsor of human culture. His primary consort was Ninhursag, the Sumerian goddess of the earth. Ninhursag was worshipped in the cities of Kesh and Adab.

Ancient Akkadian cylinder seal depicting Inanna resting her foot on the back of a lion while Ninshubur stands in front of her paying obeisance, c. 2334 - 2154 BC Inanna was the Sumerian goddess of love, sexuality, prostitution, and war. She was the divine personification of the planet Venus, the morning and evening star. Her main cult center was the Eanna temple in Uruk, which had been originally dedicated to An. Deified kings may have re-enacted the marriage of Inanna and Dumuzid with priestesses. Accounts of her parentage vary; in most myths, she is usually presented as the daughter of Nanna and Ningal, :ix-xi, xvi but, in other stories, she is the daughter of Enki or An along with an unknown mother. The Sumerians had more myths about her than any other deity.:xiii, xv Many of the myths involving her revolve around her attempts to usurp control of the other deities' domains.

Utu was god of the sun, whose primary center of worship was the E-babbar temple in Sippar. Utu was principally regarded as a dispenser of justice; he was believed to protect the righteous and punish the wicked. Nanna was god of the moon and of wisdom. He was the father of Utu and one of the patron deities of Ur. He may have also been the father of Inanna and Ereshkigal. Ningal was the wife of Nanna, as well as the mother of Utu, Inanna, and Ereshkigal.

Ereshkigal was the goddess of the Sumerian Underworld, which was known as Kur. She was Inanna's older sister. In later myth, her husband was the god Nergal. The gatekeeper of the underworld was the god Neti.

Nammu was the primeval sea (Engur), who gave birth to An (heaven) and Ki (earth) and the first deities; she eventually became known as the goddess Tiamat. An was the ancient Sumerian god of the heavens. He was the ancestor of all the other major deities and the original patron deity of Uruk.

Legacy

:

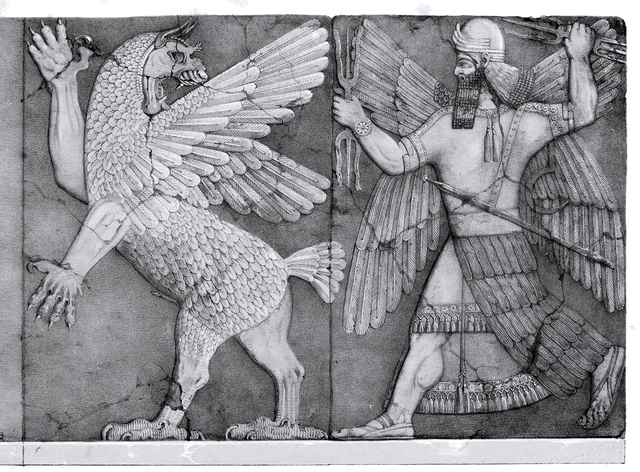

Assyrian

stone relief from the temple of Ninurta at Kalhu, showing the god

with his thunderbolts pursuing Anzû, who has stolen the Tablet

of Destinies from Enlil's sanctuary (Austen Henry Layard Monuments

of Nineveh, 2nd Series, 1853)

Babylonians

:

Hurrians

:

Parallels

:

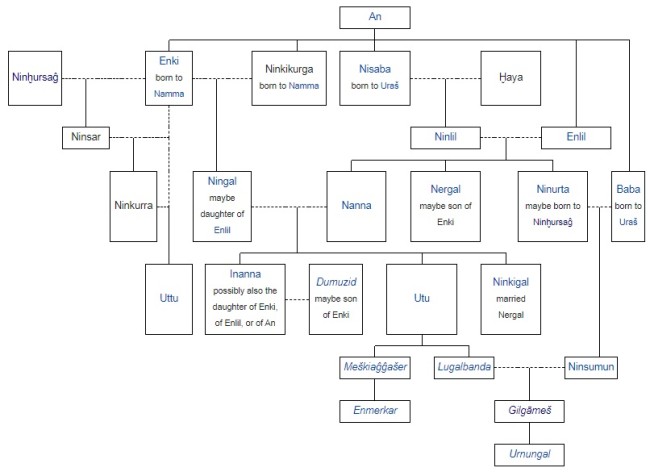

Genealogy of the Sumerian deities :

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg)