| YAZIDIS Yazidis (also written as Yezidis), are an endogamous and mostly Kurmanji-speaking minority, indigenous to Upper Mesopotamia. The majority of Yazidis remaining in the Middle East today live in Iraqi Kurdistan, primarily in the Nineveh and Dohuk governorates. There is a disagreement on whether Yazidis are a religious sub-group of Kurds or a distinct ethno-religious group, among both scholars and Yazidis themselves. The Yazidi religion is monotheistic and can be traced back to ancient Mesopotamian religions.

In August 2014, the Yazidis became victims of a genocide by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant in its campaign to eradicate non-Islamic influences.

Kurmanji :

Kurmanji (Kurdish: ,Kurmancî, meaning Kurdish), also termed Northern Kurdish, is the northern dialect of the Kurdish languages, spoken predominantly in southeast Turkey, northwest and northeast Iran, northern Iraq, northern Syria and the Caucasus and Khorasan regions. It is the most widely spoken form of Kurdish, and is a native language to some non-Kurdish minorities in Kurdistan as well, including Armenians, Chechens, Circassians, and Bulgarians.

The earliest textual record of Kurmanji Kurdish dates back to approximately the 16th century and many prominent Kurdish poets like Ahmad Khani (1650–1707) wrote in this dialect. Kurmanji Kurdish is also the common and ceremonial dialect of Yazidis. Their sacred book Mishefa Res and all prayers are written and spoken in Kurmanji.

Demographics :

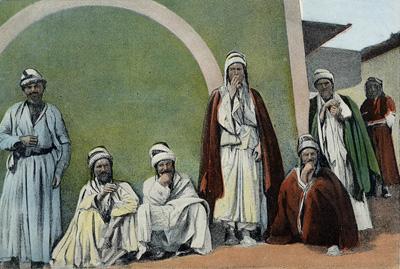

Yazidi leaders and Chaldean clergymen meeting in Mesopotamia, 19th century Historically, the Yazidis lived primarily in communities located in present-day Iraq, Turkey, and Syria and also had significant numbers in Armenia and Georgia. However, events since the end of the 20th century have resulted in considerable demographic shift in these areas as well as mass emigration. As a result, population estimates are unclear in many regions, and estimates of the size of the total population vary.

Iraq :

The majority of the Yazidi population lives in Iraq, where they make up an important minority community. Estimates of the size of these communities vary significantly, between 70,000 and 500,000. They are particularly concentrated in northern Iraq in Nineveh Governorate. The two biggest communities are in Shekhan, northeast of Mosul and in Sinjar, at the Syrian border 80 kilometres (50 mi) west of Mosul. In Shekhan is the shrine of Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir at Lalish. In the early 1900s most of the settled population of the Syrian Desert were Yazidi. During the 20th century, the Shekhan community struggled for dominance with the more conservative Sinjar community. The demographic profile has probably changed considerably since the beginning of the Iraq War in 2003 and the fall of Saddam Hussein's government.

Traditionally, Yazidis in Iraq lived in isolation and had their own villages. However, many of their villages were destroyed by the Saddam regime. The Ba'athists created collective villages and forcibly relocated the Yazidis from their historical villages which would be destroyed.

Yazidi new year celebrations in Lalish, 18 April 2017

Two Yazidi men at the new year celebrations in Lalish, 18 April 2017 According to the Human Rights Watch, Yazidis were under the Arabisation process of Saddam Hussein between 1970 and 2003. In 2009, some Yazidis who had previously lived under the Arabisation process of Saddam Hussein complained about the political tactics of the Kurdistan Region that were intended to make Yazidis identify themselves as Kurds. A report from Human Rights Watch (HRW), in 2009, declares that to incorporate disputed territories in northern Iraq—particularly the Nineveh province—into the Kurdish region, the KDP authorities had used KRG's political and economical resources to make Yazidis identify themselves as Kurds. The HRW report also criticises heavy-handed tactics."

Syria :

Yazidis in Syria live primarily in two communities, one in the Al-Jazira area and the other in the Kurd-Dagh. Population numbers for the Syrian Yazidi community are unclear. In 1963, the community was estimated at about 10,000, according to the national census, but numbers for 1987 were unavailable. There may be between about 12,000 and 15,000 Yazidis in Syria today, though more than half of the community may have emigrated from Syria since the 1980s. Estimates are further complicated by the arrival of as many as 50,000 Yazidi refugees from Iraq during the Iraq War.

Yazidi men Georgia

:

Armenia

:

The Ziarat temple in Aknalich, Armenia There is a Yazidi temple called Ziarat in the village of Aknalich in the region of Armavir. Construction on a new Yazidi temple in Aknalich, called "Quba Mere Diwan," is underway. The temple is slated to become the largest Yazidi temple in the world and is privately funded by Mirza Sloian, a Yazidi businessman based in Moscow who is originally from the Armavir region.

Turkey :

Yazidi men in Mardin, Turkey, late 19th century A sizeable part of the autochthonous Yazidi population of Turkey fled the country for present-day Armenia and Georgia starting from the late 19th century. There are additional communities in Russia and Germany due to recent migration. The Yazidi community of Turkey declined precipitously during the 20th century. Most of them have immigrated to Europe, particularly Germany; those who remain reside primarily in villages in their former heartland of Tur Abdin.

Western

Europe :

North

America :

Origins

:

Yazidi man in traditional clothes One of the important figures of Yazidism is 'Adi ibn Musafir. Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir settled in the valley of Lalis (some 58 kilometres (36 mi) northeast of Mosul) in the Yazidi mountains in the early 12th century and founded the 'Adawiyya Sufi order. He died in 1162, and his tomb at Lalis is a focal point of Yazidi pilgrimage and the principal Yazidi holy site. Yazidism has many influences: Sufi influence and imagery can be seen in the religious vocabulary, especially in the terminology of the Yazidis' esoteric literature, but much of the theology is non-Islamic. Its cosmogony apparently has many points in common with those of ancient Iranian religions blended with elements of pre-Islamic ancient Mesopotamian religious traditions.

Similarities between the Yazidis and the Yaresan are well established; some can be traced back to elements of an ancient faith that was probably dominant among Western Iranians and likened to practices of pre-Zoroastrian Mithraic religion. Mehrdad Izady defines the Yazdanism as an ancient Hurrian religion and states that Mitanni could have introduced some of the Vedic tradition that appears to be manifest in Yazdanism. Further he derived the term from a Zoroastrian concept of Holy beings (Middle Persian: Yazdan), often translated as "angels" or "archangels". While he refers to "Yazdânism" as possibly being the real name of this old religion and the sources of modern designation, 'Yezidi', he has published evidence of this assertion only in his 1992 book, Kurds: A Concise Handbook.

One of the few ancient sources that mention the "Sipâsîâns", considered synonymous with the Yazdanis is the Dabestân-e Madâheb, written between 1645 and 1658.

Early writers attempted to describe Yazidi origins, broadly speaking, in terms of Islam, or Persian, or sometimes even "pagan" religions; however, research published since the 1990s has shown such an approach to be simplistic.

Another theory of Yazidi origins is given by the Persian scholar Al-Shahrastani. According to Al-Shahrastani, the Yazidis are the followers of Yezîd bn Unaisa, who kept friendship with the first Muhakkamah before the Azari?a. The first Muhakkamah is an appellative applied to the Muslim schismatics called Al-Hawarij. Accordingly, it might be inferred that the Yazidis were originally a Harijite sub-sect. Yezid bn Unaisa moreover, is said to have been in sympathy with the Ibadis, a sect founded by 'Abd-Allah Ibn Ibad.

Identity :

Yazidi girls in traditional dress

A 2014 documentary on the Yazidis Yazidi cultural practices are observed in Kurmanji, which is also used by almost all the orally transmitted religious traditions of the Yazidis. However, the Yazidis in Bashiqa and Bahzani speak Arabic as their mother language. Although the Yazidis speak mostly in Kurmanji, their exact origin is a matter of dispute among scholars, even among the community itself as well as among Kurds, whether they are ethnically Kurds or form a distinct ethnic group. Yazidis only intermarry with other Yazidis; those who marry non-Yazidis are expelled from their family and are not allowed to call themselves Yazidis.

Some modern Yazidis identify as a subset of the Kurdish people while others identify as a separate ethno-religious group. In Armenia and Iraq, the Yazidis are recognized as a distinct ethnic group. According to Armenian anthropologist Levon Abrahamian, Yazidis generally believe that Muslim Kurds betrayed Yazidism by converting to Islam, while Yazidis remained faithful to the religion of their ancestors. In the autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Yazidis are considered ethnic Kurds and the autonomous region considers Yazidis to be the "original Kurds". The sole Yazidi parliamentarian in the Iraqi Parliament Vian Dakhil also stated her opposition to any move separating Yazidis from Kurds.

Yazidis are also regarded as ethnic Kurds in Georgia. The Soviet Union registered the Yazidis and the Kurds as two different ethnic groups for the 1926 census, but bulked the two together as one ethnicity in the censuses from 1931 to 1989. Sharaf Khan Bidlisi's Sheref-nameh of 1597, which cites seven of the Kurdish tribes as being at least partly Yazidi, and Kurdish tribal confederations as containing substantial Yazidi sections.

Conversely, during his research trips in 1895, anthropologist Ernest Chantre visited the Yazidis in today's Turkey and reported that Yazidis claimed that Kurds spoke their language and not vice-versa.

Historically, there have been persecutions against Yazidis at the hand of some Kurdish tribes. and this persecution has on numerous occasions threatened the existence of Yazidis as a distinct group. Some Yazidi tribes converted to Islam and embraced the Kurdish identity.

Religion

:

Genetics

:

Western

perceptions :

In Western literature :

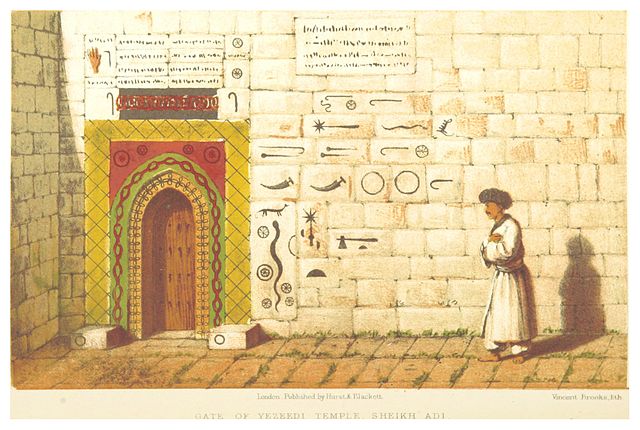

Image from A journey from London to Persepolis, 1865 In William Seabrook's book Adventures in Arabia, the fourth section, starting with Chapter 14, is devoted to the "Yezidees" and is titled "Among the Yezidees". He describes them as "a mysterious sect scattered throughout the Orient, strongest in North Arabia, feared and hated both by Moslem and Christian, because they are worshippers of Satan." In the three chapters of the book, he completely describes the area, including the fact that this territory, including their holiest city of Sheik-Adi, was not part of "Irak".

George Gurdjieff wrote about his encounters with the Yazidis several times in his book Meetings with Remarkable Men, mentioning that they are considered to be "devil worshippers" by other ethnicities in the region. Also, in Peter Ouspensky's book "In Search of the Miraculous", he describes some strange customs that Gurdjieff observed in Yazidi boys: "He told me, among other things, that when he was a child he had often observed how Yezidi boys were unable to step out of a circle traced round them on the ground" (p. 36).

Idries Shah, writing under the pen-name Arkon Daraul, in the 1961 book Secret Societies Yesterday and Today, describes discovering a Yazidi-influenced secret society in the London suburbs called the "Order of the Peacock Angel." Shah claimed Tawûsê Melek could be understood, from the Sufi viewpoint, as an allegory of the higher powers in humanity.

In H.P. Lovecraft's story "The Horror at Red Hook", some of the murderous foreigners are identified as belonging to "the Yezidi clan of devil-worshippers".

In Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey-Maturin series novel The Letter of Marque, set during the Napoleonic wars, there is a Yazidi character named Adi. His ethnicity is referred to as "Dasni".

A fictional Yazidi character of note is the super-powered police officer King Peacock of the Top 10 series (and related comics). He is portrayed as a kind, peaceful character with a broad knowledge of religion and mythology. He is depicted as conservative, ethical, and highly principled in family life. An incredibly powerful martial artist, he is able to perceive and strike at his opponent's weakest spots, a power that he claims is derived from communicating with Malek Ta'us.

In

US Army memoirs :

In an October 2006 article in The New Republic, Lawrence F. Kaplan echoes Williams's sentiments about the enthusiasm of the Yazidis for the American occupation of Iraq, in part because the Americans protect them from oppression by militant Muslims and the nearby Kurds. Kaplan notes that the peace and calm of Sinjar is virtually unique in Iraq: "Parents and children line the streets when U.S. patrols pass by, while Yazidi clerics pray for the welfare of U.S. forces."

Tony

Lagouranis comments on a Yazidi prisoner in his book Fear Up Harsh:

An Army Interrogator's Dark Journey through Iraq :

Persecution

of Yazidis :

Under

the Ottoman Empire :

In

post-invasion Iraq :

By the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) :

Defend International provided humanitarian aid to Yazidi refugees in Iraqi Kurdistan in December 2014 In 2014, with the territorial gains of the Salafist militant group calling itself the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) there was much upheaval in the Iraqi Yazidi population. ISIL captured Sinjar in August 2014 following the withdrawal of Peshmerga troops of Masoud Barzani, forcing up to 50,000 Yazidis to flee into the nearby mountainous region. In early August the town of Sinjar was nearly deserted as Kurdish Peshmerga forces were no longer able to keep ISIL forces from advancing. ISIL had previously declared the Yazidis to be devil worshippers and had taken the two nearby small oil fields and the town of Zumar as part of a plan to try to seize Mosul's hydroelectric dam. Up to 200,000 people (including an estimated 40,000 Yazidi) fled the city before it was captured by ISIL forces, giving rise to fears of a humanitarian tragedy. Alongside the local Yazidis fleeing Sinjar were Yazidis (and Shiites) who fled to the city a month earlier when ISIL captured the town of Tal Afar.

Most of the population fleeing Sinjar retreated by trekking up nearby mountains with the ultimate goal of reaching Dohuk in Iraqi Kurdistan (normally a five-hour drive by car). Concerns for the elderly and those of fragile health were expressed by the refugees, who told reporters of their lack of water. Reports coming from Sinjar stated that sick or elderly Yazidi who could not make the trek were being executed by ISIL. Yazidi parliamentarian Haji Ghandour told reporters that "In our history, we have suffered 72 massacres. We are worried Sinjar could be a 73rd."

UN groups say at least 40,000 members of the Yazidi sect, many of them women and children, took refuge in nine locations on Mount Sinjar, a craggy, 1,400 m (4,600 ft) high ridge identified in local legend as the final resting place of Noah's Ark, facing slaughter at the hands of jihadists surrounding them below if they fled, or death by dehydration if they stayed. Between 20,000 and 30,000 Yazidis, most of them women and children, besieged by ISIL, escaped from the mountain after the People's Protection Units (YPG) and Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) intervened to stop ISIL and opened a humanitarian corridor for them, helping them cross the Tigris into Rojava. Some Yazidis were later escorted back to Iraqi Kurdistan by Peshmerga and YPG forces, Kurdish officials have said.

Their plight received international media coverage, which led United States President Barack Obama to authorise humanitarian airdrops of meals and water to thousands of Yazidi and Christian religious minorities trapped on Sinjar mountain. President Obama also authorised "targeted airstrikes" against Islamic militants in support of the beleaguered religious minority, and to protect American military personnel in northwest Iraq. American humanitarian assistance began on 7 August 2014, with the UK Royal Air Force subsequently contributing to the relief effort. At an emergency meeting in London, Australian prime minister Tony Abbott also pledged humanitarian support, while European nations resolved to join the US in helping to arm Peshmerga fighters aiding the Yazidis with more advanced weaponry.

Later PKK and YPG fighters with Peshmergas and support of the US airstrikes helped the rest of the trapped Yazidis to escape from the mountain. One relief worker in the evacuation operation described the conditions on Mount Sinjar as "a genocide", having witnessed hundreds of corpses. Yazidi girls in Iraq allegedly raped by ISIL fighters have committed suicide by jumping to their death from Mount Sinjar, as described in a witness statement. In Sinjar, ISIL destroyed a Shiite shrine and demanded that the remaining population convert to their version of Islam, pay jizya (a religious tax) or be executed.

Captured women are treated as sex slaves or spoils of war, some are driven to suicide. Women and girls who convert to Islam are sold as brides, those who refuse to convert are tortured, raped and eventually murdered. Babies born in the prison where the women are held are taken from their mothers to an unknown fate. Nadia Murad, a Yazidi human rights activist and 2018 Nobel Peace Prize winner, was kidnapped and used as a sex slave by the ISIL in 2014.

Haleh Esfandiari from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars has highlighted the abuse of local women by ISIL militants after they have captured an area. "They usually take the older women to a makeshift slave market and try to sell them. The younger girls ... are raped or married off to fighters", she said, adding, "It's based on temporary marriages, and once these fighters have had sex with these young girls, they just pass them on to other fighters." Speaking of Yazidi women captured by ISIL, Nazand Begikhani said "[t]hese women have been treated like cattle... They have been subjected to physical and sexual violence, including systematic rape and sex slavery. They've been exposed in markets in Mosul and in Raqqa, Syria, carrying price tags." Dr. Widad Akrawi said that ISIL uses slavery and rape as weapons of war.

In September 2014, Defend International launched a worldwide campaign entitled "Save The Yazidis: The World Has To Act Now" to raise awareness about the tragedy of the Yazidis in Sinjar and to co-ordinate activities related to intensifying efforts aimed at rescuing Yazidi and Christian women and girls captured by ISIL. In October 2014, the United Nations reported that more than 5,000 Yazidis had been murdered and 5,000 to 7,000 (mostly women and children) had been abducted by ISIL. In the same month, President of Defend International dedicated her 2014 International Pfeffer Peace Award to the Yazidis. She asked the international community to make sure that the victims are not forgotten; they should be rescued, protected, fully assisted and compensated fairly.

ISIS has, in their digital magazine Dabiq, explicitly claimed religious justification for enslaving Yazidi women. In December 2014, Amnesty International published a report. Despite the oppression Yazidis' women have sustained, they have appeared on the news as examples of retaliation. They have received training and taken positions at the frontlines of the fighting, making up about a third of the Kurd–Yazidi coalition forces, and have distinguished themselves as soldiers.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |