| VARUN, VED AND ZOROASTRIANISM Chapter - 7

Varun and Ahura Mazda :

It is generally accepted that the Ahura Mazda of the Avesta is indeed the Varun of Rig Ved. Before we come to that let’s talk of few other things.

X. Before parting of ways :

The Old World :

78.1. In the Vedic times the people on either side of the great river Sindhu were closely related. The communities that lived in what is Iran today and in what is Sind and Punjab today shared common traditions, myths and legends as also a common cultural milieu. Their faith, as also many of their religious rites were virtually the same; and were often called by same or similar names. The language spoken on either side of the great river; the words, grammar and syntax of the idioms sprung from same roots.

78.2. For, in those days what we now call the frontier between the two lands—the imaginary line dividing people of imaginary differences—did not exist; the Vedic people populated both Iran and India equally freely. They established kingdoms, formed alliances, and created common systems of: worship, living and trade; as also measurement and mathematics. They developed ongoing cultural and trade contacts with peoples of rival cultures as far away as Mesopotamia, Phoenicia and even Egypt; and carried their language so far west that the westernmost Isles of the Eurasian land mass came to be called “Eire” after Arya the term used by these people to describe themselves.

The gods and the priests :

78.3. Of the gods worshipped on both the sides, Indra the Deva and Varun the mighty Asura were prominent. The worship was commonly through the medium of the formless fire (Agni); they prayed to Agni to lead them along the good path (Agneye naya supatha rayé asman – YajurVed 40.17). It appears that the older deity Varun who upholds the moral order was more widely accepted in the western region (Iran) while Indra the warrior god had more followers on the east of the Sindhu. The priests guiding the communities on the west of the great river were the Bhrigus (identified by some scholars as the tribe of the Anu or Anva), while Angirasas were the priests of the Puru people and of the dominant Bharatas on the eastern side. There was certain amount of rivalry between the Bhrigus and the Angirasas though both groups came from same stock (descendents of Prajapathi). It was not, therefore, a conflict between two diverse cultures. What separated the two clans was the conflict of ideas and rivalry rather than as enmity. That rivalry went far back into the pre-Vedic past. During the times of the early Rig Ved the Angirasas were regarded the dominant priests, while the Bhrigus or the Atharvanas synonymous with fire-priests were on the fringe.

The Bhrigus :

79.1. The Bhrigus, also known as Bhargavas, are the descendents of the sage Bhrigu. The cult of the sage Bhrigu whose name derives from the root bhrk meaning ‘the blazing of the fire’ professed immense reverence towards the elements of fire on earth viz the life and warmth-giving Sun and the Fire. Though all Rishis, in general, have associations with these two elements, the Bhrigus’ attachment to fire was a special one. They were the first to introduce the fire-ritual and the Soma-ritual; and were the first to discover the nexus between fire and water (Apam Napat).The Bhrigus were associated with water as also fire. The fire-worshipping Bhrigus were close to the life on seas, rivers. The vast stretch of the mouths of the mighty Sindhu as it branched into number of rivulets to join the occasion was the region of the Bhrigus. It is where they resided and flourished. That is the reason that the present day Baruch was known as Bhrigu-kaksha or Bhrigu kaccha the region of the Bhrigus.

79.2. The Bhrigus followed the doctrine of the ancestors (pitris) or the older gods (Asura). The Supreme Asura the Father -Varun the Asura Mahat (the mighty Asura) was highly venerated by the Bhrigus. The Bhrigu cult which adopted monotheistic approach wholly favoured the worship of the invisible Asura the Father Varun through the medium of the formless fire Agni that lights the path of the Fathers (the fire does not have much of a form—at least not a static one). They dis-favoured icon worship. The Bhrigus strived to abide by Rta the physical and moral laws of Varun. And, insisted on sharp distinctions between the good and evil.

79.3. The main text of the Bhrigus was the Atharvana Ved. They were, in particular, known as Atharvans. Sri Sayana-charya described the Atharvanas as of firm resolve and steadfast mind. Elsewhere, Bhrigus were described as very proud people, hot tempered and independent. It is said; they valued free thinking more than the rules. Bhrigus were also the expert physicians, mathematicians, architects and artists. The Bhrigus compiled their almanac with reference to the star by the name of their preceptor Shukra (Venus)) [as did the ancient Egyptians, Mayas, Incas, Assyrians, and Babylonians].

The Angirasas :

80.1. In contrast, the Angirasas who professed worship of younger gods (Deva) were the preceptors of the Puru Aryans the heroes of Rig Ved on the east of the Sindhu. The name Angirasa too is connected with fire as the ‘glowing coal or the shouldering ember’ (Angara).The Angirasas are described as the sons of the flame resembling the lustre of the dawn and as the drinkers of Soma. They are hailed as the warriors, the fighters for the cows or rays of sun (gosu yodhaah); and are credited with gaining back the cows, the horses, the waters and all treasures from the grasp of the sons of Darkness. Their association with the Dawn and the Sun and the Cows comes through in several ways.

80.2. Angirasas were dexterous users of words and were superb poets. They are the masters of the Rik who expressed their thought with clarity and brightness (svaadhibhir rkvabhih – RV: 6. 32.2).Their poetry is charged with high idealism, soaring human aspirations and an intense desire to grow out of the limited human confines. Angirasa are said to have composed the very first verse of the Rig Ved, the hymn to Agni.

80.3. The Angirasas were more closely associated with mountains, hills, dales, vast open spaces; and were mainly in the foothill regions of the Himalayas. They were more attuned to contemplation and pursuit of knowledge (than wealth and pleasure). They adopted the yajna and soma practices from the Bhrigus. The Angirasas compiled their almanac with reference to star bearing the name of their preceptor Brihaspathi, Guru (Jupiter) [as did the people of ancient Chinese, Japanese, Malaya, Indonesia, etc].

Bhrigu –Angirasa rift :

81.1. Though both the Bhrigus and Angirasas were closely associated with fire, the Bhrigus in particular came to be known as the Atharvanas- the high priests who worship fire. Further, though both Bhrigus and Angirasas performed Yajna with great fervour, the latter tended to personify the gods and to lend them a form (murtha).This tendency to shift towards worship the formless through a personalized form or an idol (murti) seems to have displeased the Bhrigus and exacerbated the rift between the two great sages and their followers. The Bhrigus on the west of the Sindhu asserted their method of worship was pristine and their gods who were more ancient (Asura). The Angirasas on the other hand believed that the younger gods (Deva) were more dynamic, powerful and more responsive to prayers. Each group tended to look down upon the other; and to decry the gods of the rival cult.

81.2. The rise of Indra the king of Devas and the steep decline of Varun the Asura and his eventual eclipse in the Vedic pantheon had lot to do with widening the rift between the clans of the two sages. Varun in the early Rig Ved was a highly venerated god. He was hailed as the sole sovereign sky-god; the powerful Asura, the King of both men and gods, and of all that exists. He governed the laws of nature as also the ethical conduct of men. But with time, Varun was steadily stripped of his powers one-by-one and relegated to a very minor rank. Further, one of the most fundamental aspects of Varun the Rta, which signified the greatest good not merely ensured the physical order but also the moral order in the universe, was given a goby.

81.3. The shabby treatment meted out to Varun the Asura Mahat, the watering down the laws of Varun the Rta offended the Bhrigu clan greatly. Bhrigu was after all the son of Varun.

The Bhrigus professed monotheism and formless worship of Varun; and stood by Rta. Even while the battles of minds and hearts were being waged the rival groups lived side by side.

Y. Rift formalized :

Separation of Books :

82.1. The rift between the two clans was more or less formalized when the composite text Atharvana Ved, also called Bhrigu – Angirasa Samhita, was split into two books along the lines of their affiliations: the Bhargava Ved (the Ved of the Bhrigus) and Angirasa Ved (the Ved of the Angirasa).It is believed that the Atharva Ved which has come down to us in India is, in fact, only one-half of the original text – the Angirasa Ved part. The other half the Bhargava Ved is lost to us.

82.2. Shri Jatindra Mohan Chatterji argues that the Bhrigus whose notions of God, of his worship and of the moral order were not well accepted in the east took with them their sacred text Bhargava Ved over to the west of the Sindhu River. Shri Chatterji says that Zend Avesta is the Bhargava Ved text that was lost to India. He asserts that the Bhargava Ved the missing Book of the Bhrigu Angirasa Samhita is indeed the Zend Avesta (The Hymns of Atharvan Zarathustra – Published by The Parsi Zoroastrian Association, Calcutta, 1967).

82.3. Thus, the Indo-Iranians became divided into two groups of people on the basis of the method of worship and accent on certain principles. And it is apparently this division that led to the breakup of the original Aryan Land into two parts: Iran and India. In the process, both countries lost something. Iran, on the one hand, lost the Rig Ved, with its hymns in praise of Indra and along with it the Saman and Yajus as well. India, on the other hand, lost half of the Atharva Ved, namely the Bhragava Samhita or Bhargava Ved. Thereafter due to vicissitudes and ironies of history the two lands could never come together again. They, sadly, remain separated- forever.

82.4. When the Aryan community was undivided the terms Asura and Deva both denoted gods of high respect. The gods were referred to Asura as also Deva. But with the parting of their ways each tribe accorded its own chosen words of abuse to the terms Asura or Deva, depending on to which side of the Sindhu they belonged.

Z …. And after :

Language of the Avesta and Vedic Sanskrit :

83.1. The Zend Avesta (chhanda = verse, meter; Avesta = apistaka = pusthaka) literally means the Book of Hymns, which indeed was the nature of the Bhragava Samhita or Bhargava Ved. Shri JM Chatterji observes that the language of the Avesta and the language of the Veds resemble very closely since they are based in a common linguistic foundation.

It is said; their relation is so close that entire passages from the Gathas can be rendered into Vedic Sanskrit by application of the phonetic rules – that is by exchanging some sounds for others- such as S for Sh; Z for Zh; and ,C for Ch. For instance; the Sanskrit terms aham (‘I’), jihva (tounge), sapta (seven), hima (snow) and yajna (sacrifice ritual) would become ajem, hijva, hapta, zyma, and yasna, respectively, in the Iranian texts. Similarly Pita (Sk) would be Pitar (Av); Mans (Sk) – Manah (Av); Hotar (Sk) – Zotar (Av); Mitra (Sk) – Mithra (Av); Arya (Sk)-Ariyan (Av); and, Martyanam (Sk) – Masyanam (Av) and so on. Such rendering can produce verses in Sanskrit that are correct not only in form but also in poetic flow. Further, some terms – e.g. Shukra (bright), Krishna (dark) – carry the same form and meaning in either text.

83.2. One could find a Sanskrit equivalent for almost any Avestan word. For instance: The Avesthan : aevo pantao yo ashahe, vispe anyaesham apantam (Yasna 72.11); could be rendered in Sanskrit as : abade pantha he ashae, visha anyaesham apantham (translation: The one path is that of Asha, all others are not-paths).

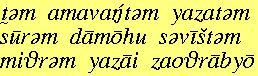

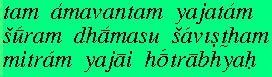

Another example (left) of Avestan text from Yasna 10.6 is rendered word for word in Sanskrit on the right. Translated it means: `Mithra that strong mighty angel, most beneficent to all creatures, I will worship with libations’

83.3. The Cambridge History of India observes, “The coincidence between the Avesta and the Rig-Ved is so striking that the two languages cannot have been long separated before they arrived at their present condition.” The linguist, Professor T. Burrow of Oxford University also argued for strong similarities between language of Avesta and Vedic Sanskrit. And, HD Griswold (in his The Religion of the Rig Ved) went so far as to point out that each can be said to be “a commentary on the other … No scholar of the Avesta worth the designation can do without a thorough grounding in Vedic Sanskrit”.

Similarities and differences between Rig Vedic Sanskrit and Avestan.

Source : Encyclopedia Britannica.

The long and short varieties of the Indo-European vowels e, o, and a, for example, appear as long and short a: Sanskritmanas- “mind, spirit,” Avestanmanah-, but Greek ménos “ardour, force; Greek pater “father,” Sanskrit pitr-, Avestan and Old Persian pitar-.

After stems ending in long or short a, i, or u, an n occurs sometimes before the genitive (possessive) plural ending am (Avestan -am)—e.g., Sanskrit martyanam “of mortals, men” (from martya-); Avestan mašyanam (from mašya-); Old Persian martiyanam.In addition to several other similarities in their grammatical systems, Indo-Aryan and Iranian have vocabulary items in common—e.g., such religious terms as Sanskrit yajña-, Avestan yasna- “sacrifice”; and Sanskrit hotr-,zaotar- “a certain priest”; as well as names of divinities and mythological persons, such as Sanskrit mitra-, Avestan miqra- “Mithra.”

Indeed, speakers of both language subgroups used the same word to refer to themselves as a people: Sanskrit arya-, Avestan airya-, Old Persian ariya- “Aryan.” Avestan.

The Indo-Aryan and Iranian language subgroups also differ duhitr- “daughter” (cf. Greek thugáter). In Iranian, however, the sound is lost in this position; e.g., Avestan dugdar-, dudar-. Similarly, the word for “deep” is Sanskrit gabhira- (with i for i), but Avestan jafra-. Iranian also lost the accompanying aspiration (a puff of breath, written as h) that is retained in certain Indo-Aryan consonants; e.g., Sanskrit dha “set, make,” bhr, “bear,” gharma- “warm,” but Avestan and Old Persian da, bar, and Avestan garma-.

Further, Iranian changed stops such as p before consonants and r and v to spirants such as f: Sanskrit pra “forth,” Avestan fra; Old Persian fra; Sanskrit putra- “son,” Avestan puqra-, Old Persian pusa- (s represents a sound that is also transliterated as ç).

In addition, h replaced s in Iranian except before non-nasal stops (produced by releasing the breath through the mouth) and after i, u, r, k; e.g., Avestan hapta- “seven,” Sanskrit sapta-; Avestan haurva- “every, all, whole,” Sanskrit sarva-. Iranian also has both xš and š sounds, resulting from different Indo-European k sounds followed by s-like sounds, but Indo-Aryan has only ks; e.g., Avestan xšayeiti “has power, is capable,” šaeiti “dwells,” but Sanskrit ksayati, kseti. Iranian was also relatively conservative in retaining diphthongs that were changed to simple vowels in Indo-Aryan.Iranian differs from Indo-Aryan in grammatical features as well.

The dative singular of -a-stems ends in -ai in Iranian; e.g., Avestan mašyai, Old Persian cartanaiy “to do” (an original dative singular form functioning as infinitive of the verb).

In Sanskrit the ending is extended with a—martyay-a. Avestan also retains the archaic pronoun forms yuš, yuzm “you” (nominative plural); in Indo-Aryan the -s- was replaced by y (yuyam) on the model of the 1st person plural—vayam “we” (Avestan vaem, Old Persian vayam).

Finally, Iranian has a 3rd person pronoun di (accusative dim) that has no counterpart in Indo-Aryan but has one in Baltic.]

Zend Avesta and the Gathas :

84.1. Zend Avesta is the oldest and the most famous religious text of Iran. As mentioned earlier, it is believed to be a version of the Vedic text Bhrigu Ved of the Atharva Ved. The Avesta comprises four books: Yasna (book of hymns), Yashta (book of prayers), visparatau (book of Rta or righteousness) and vidaevadata (book of laws). The hymns composed by the prophet Zarathustra are inserted into the original text of the Avesta in the Book of Yasna. His hymns – Gatha (Gita or songs) numbering seventeen consisting 238 verses are indeed the core and cream of the Avesta despite the fact that they form only a tiny portion of the whole text. These Gathas of inspired poetry composed in ancient form were sung by Zarathustra the poet-prophet to invoke and glorify the Great God Ahura Mazda. They are highly devotional in nature expounding the essence of Rta (Asha) the greatest good, the good mind (voshu) and righteousness. They also reveal the mind and the personality of Zarathustra the first prophet of mankind. He exhorts people to lead a life of righteousness as directed by Ahura Mazda.

The Gathas also contain biographical glimpses of Zarathustra.

Zarathustra :

85.1. The traditions of Iran believe that Ratu (Rishi) Zarathustra descended from a long line of sage-kings (Raja-rishi). Zarathustra describes himself : as of the Bhrigu clan, a Bhargava ‘ I am Spitama Zarathustra’ (the Avestan term Spitatama = shukla (Snkt) = white which is the colour associated with Bhrigu); as in the line of sage Vashishtha (Vahishta in the Avesta: Vahishtem Thwa Vahishta yem); as an Atharvan (fire priest); as a Zoatar (hotar (Snkt)= priest officiating at the yajna) ; as a reciter of Mantras (Mantrono dutim –Ys.32.13) ; and as a Mantra teacher (Manthra-ne :Ys.50.5).

85.2. He declares that “silent meditation is the best for man” (Ys.43.15); and exhorts to worship the formless-one “in essence and in vision’ (Ys.33.71). He was not very fond of rites and rituals; and was positively against worship of icons. Zarathustra proclaimed his immense faith in the Great One; and said that the formless Supreme can be realized through intense Love alone (in the sense of deep Bhakthi) –“, O Ahura, Who Art the Greatest Good; with love would I worship Thee” (Gatha: 28.82). According to Shri JM Chatterji, Zarathustra was a Vedic sage in the line of Bhrigu and Vashista; and the Gathas resemble in tenor and spirit the devote and forceful hymns sung in praise of Varun by sage Vashista in the Atharva Ved (AV.4.16.7-8).

85.3. Scholars believe that Zarathustra lived during the late Vedic age when Varun was being phased out; when he was no longer the greatest god; and when Indra ruled as the king of gods. Given the fact that he lived in the regions west of the Sindhu and that he belonged to the Bhrigu-clan, Zarathustra was naturally inclined towards the worship of Varun the formless Great Asura. There is therefore in Zarathustra’s hymns a strong streak of monotheism; great love for his God; immense faith in prayers and in God’s mercy; and a very clear and a precise moral sense of the right and the wrong.

Ahura Mazda :

86.1. Zarathustra declared there is only one God and He is formless. He is the only one worthy of highest worship. Zarathustra gave that ‘formless mighty spirit’ one and only one name: Ahura Mazda. Zarathustra’s monotheism is so strict and uncompromising that never in his Gathas does he address or refer to his God by any other name. And, he declared ‘Ahura Mazda alone is worthy of worship’ (Gatha: 29.4).

86.2. The terms Ahura (Asura= the formless mighty lord) and Mazda (Mahat = Greatest; or Medha = Vedhas = wise) were already in use and well known in the eastern regions of Iran as alternate names of the ancient god Varun. The virtues and attributes of Varun were also well known. But, ever since Zarathustra employed the compound term -Ahura Mazda – it became widely accepted in preference to the earlier name Varun.

86.3. Ahura Mazda was conceived as a formless invisible God. The prime attribute of the invisible God is his essence. Zarathustra visualized his God in his heart and mind; and described him in varieties of ways. Zarathustra sang the glory of his God Ahura Mazda the spirit in his being as :

the uncreated God; the mighty formless spirit; highest deity; wholly wise, benevolent and good; Most beneficent spirit; Maker of the material world; Holy One; the creator and upholder of the moral order Asha (Rta); All-Wise Lord of All He Surveys; the source of all goodness; the friend of the righteous, the destroyer of the evil and the creator of the universe which is completely good.

86.4. He bursts into a series of superlatives: the All Brilliant; the All Majestic; the All Greatest;;the Greatest Good; Most Beneficent Spirit; the Best(Vahishtem); and the Most Beautiful (Ys: 31 .21).

86.5. Zarathustra describes Ahura Mazda in as many as one hundred-and-one epithets, of which the forty-fourth is Varun. In the Avesta, Varun stands for the ‘all –embracing sky’.

86.6. Ahura Mazda was invoked in a triad, with Mithra and Apam Napat (described as the spirit of the waters). Ahura Mazda was not worshiped through a murti or an idol; in fact, the idols were smitten in the congregations.

[Till the Achaemenid period (ca. 550–330 BC) it was customary for the emperors to have an empty chariot drawn by white horses to honour Ahura Mazda. However, stone carved Images of Ahura Mazda began to appear in the Parathion period (ca.129 BC-224 AD).]

86.7. Further, In the Gathas where the battle between good and evil is a distinguishing characteristic of the religion, the Daevas (Devas the Vedic gods) are the “wrong gods”, the followers of whom need to be brought back to the path of the ‘good religion’.

Ahura Mazda and Varun :

87.1. Scholars, who have studied the Gathas closely, observe the virtues, powers and attributes of Ahura Mazda and that of Varun of the Rig Ved are almost identical. Many strongly believe that Ahura Mazda is indeed the Varun. For instance, Bloomfield (in his Hymns of the Atharva-Ved, Sacred Books of the East, 1897) declared: “It seems to me an almost unimaginable feat of scepticism to doubt the original identity of Varun and Mazda”. And, similarly Nichol Manicol (Indian Theism, London, 1915) observed that “the evidence that identifies Varun with Mazda is too strong to be rejected”.

Rta and Asha :

We need to talk a bit more about Rta the very heart of Varun-doctrine and hence the core of Zarathustra’s Gathas.

88.1. Rta in Rig Ved is the principle that supports and upholds all creation; it governs the physical and moral order in the universe. Rta in the Avesta is termed Asha; and Asha carries the same connotation as Rta. Asha the greatest good of all is the basic and the most important tenet of the Avesta. The term Asha occurs in the Avesta texts in a variety of forms such as: asha, arsh, eresh, arta and ereta.

88.2. Asha is raised to a very exalted position; to the level of Ahura Mazda himself. Ahura Mazda is described as ‘of one accord with Asha’; and as one ‘who is highest in Asha, and one who has advanced furthest in Asha.’

Asha is the changeless eternal law of Ahura .It was in accordance with that law that the universe came into being; it is by Asha that the universe is sustained; and it is by obeying which universe is progressing towards its destiny and fulfilment.

As the moral order in the Universe, Asha signifies righteousness, Truth, Justice and Divine will. Asha is also the spiritual enlightenment. As it usually happens, it is hard to find an exact term in English language to capture an Indian concept. It is the case with Rta and Asha too.

88.3. A prayer calls out Asha as “the Love, the greatest Love and the enlightenment of he who honours Asha just for the love of it”; and yearns “Through the best Asha, through the highest Asha, may we get a vision of Thee O Ahura Mazda, may we draw near unto Thee, may we be in perfect union with Thee” (Ys.60.12).Finally “there is but one path…the path of Asha; all the rest are false” (Ys.71.11)

Great Reformer :

89.1. Zarathustra was not only a great prophet but was also a great reformer. He did not overthrow the older Vedic region and its beliefs. Instead, he reformed the ancient religion and lent it a definite sense of direction. [In a way, the religion of Zarathustra is closer to the Vedic religion than is the Buddhism.]

89.2. Zarathustra re-established Varun and his doctrine of moral order, of Love and of faith in God. He placed the formless and unseen, the one and only God at the centre of kingdom of justice. He emphasized the dichotomy of the good and bad; the value systems and the wisdom in life. He asked his people to Love God and the Truth for its own sake. He played down the role of rituals and encouraged contemplation; exhorted to worship the formless God ‘in essence and vision’ and to seek him in silent meditation.

89.3. Varun symbolized purity in life in all its aspects. Zarathustra sought to re-establish in his land the sense of purity as also the values and the wisdom of the ancient Great and Noble God Varun.

[ I fondly recall my dear departed friend Dorabjee ( whose story you read earlier; if you have not , please do read now my tribute to an old friend ) . It was Dorabjee who during my early years in Bombay led me to acquaintance with the Gathas of Zarathustra and to the realization how close they were to the hymns of Atharva Ved. I trust my friend, wherever he is, would not be displeased with my effort.]

References and Sources :

1. Indra and Varuna in Indian Mythology by Dr. Usha Choudhuri; Nag Publishers, Delhi, 1981

2. The Indian Theogony by Dr.Sukumari Bhattarcharji, Cambridge University Press, 1970

3. Asura in early Vedic religion by WE Hale; Motilal Banarsidass; Delhi, 1986

4. Goddesses in ancient India by PK Agrawala; Abhinav Publications, New Delhi,1984

5. The Hymns of Atharvan Zarathustra by JM Chatterji; the Parsi Zoroastrian Association, Calcutta, 1967

www.avesta.org

6. Outlines of Indian Philosophy –Prof M Hiriyanna; Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 2005

7.Original Sanskrit texts on the 0rigin and history of the people of India, their region and institution By J. Muir;Trubner & co., London, 1870.

8. A classical dictionary of Hindu mythology and religion, geography, history, and literature byJohn Dowson; Turner & co, Ludgate hill. 1879. 9. Vaidika Sahitya Charitre by Dr. NS Anantharangachar; DVK Murthy, Mysore, 1968

10. Sri Brahmiya Chitra Karma sastram by Dr. G. Gnanananda

11. Zarathustra Chapters 1-6 by Ardeshir Mehta; February 1999

Websites :

indiayogi.com

bookrags.com

bookrags.com

hinduweb.org

rashmun.sulekha.com

newworldencyclopedia.org

indiadivine.org

svabhinava.org

en.wikipedia.org

iamronen.com

hummaa.com |