| KAPISA / KAPIS / KAPISI Part 1 :

Kapis Province :

Kapis is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan. Located in the north-east of the country. The population of Kapis is estimated to be 496,840, although there has never been an official estimate. The province covers an area of 1,842 km2 (711 sq mi) making it the smallest province in the country, however it is the most densely populated province apart from Kabul Province. It borders Panjshir Province to the north, Laghman Province to the east, Kabul Province to the south and Parwan Province to the west. Mahmud-i-Raqi is the provincial capital, while the most populous city and district of Kapis is Nijrab. Clashes have been reported in the province since the 2021 Taliban takeover of Afghanistan.

Kapis Province

Map of Afghanistan with Kapis highlighted Coordinates

(Capital) : 35.0° N 69.7° E

The earliest references to Kapis appear in the writings of fifth century BCE Indian scholar Panini. Panini refers to the city of Kapisi, a city of the Kapis kingdom, modern Bagram. Panini also refers to Kapisyan, a famous wine from Kapis. The city of Kapisi also appeared as Kavisiye on Graeco-Indian coins of Apollodotus I and Eucratides.

Archeological discoveries in 1939 confirmed that the city of Kapis was an emporium for Kapisyan wine, bringing to light numerous glass flasks, fish-shaped wine jars, and drinking cups typical of the wine trade of the era. The grapes (Kapisyani Draksh) and wine (Kapisyani Madhu) of the area are referred to in several works of ancient Indian literature. The epic Mahabharat also mentions the common practice of slavery in the city.

Based on the account of the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, who visited in AD 644, it seems that in later times Kapis was part of a kingdom ruled by a kshatriya king holding sway over ten neighboring states, including Lampak, Nagarahar, Gandhar, and Banu. Xuanzang notes the Shen breed of horses from the area, and also notes the production of many types of cereals and fruits, as well as a scented root called Yu-kin.

Kapis

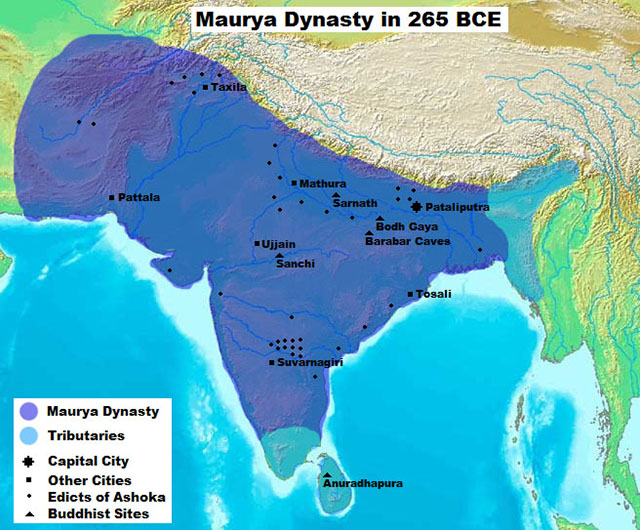

province under the Mauryan Empire rule :

Maurya Empire under Ashok the Great :

Maurya Empire under Ashoka the Great Alexander took these away from the Aryans and established settlements of his own, but lasted only a decade before Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupt), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants. —

Strabo, 64 BCE – 24 CE

— Junianus Justinus

Newly

excavated Buddhist stupa at Mes Aynak in Logar Province of Afghanistan.

Similar stupas have been discovered in neighboring Ghazni Province,

including in the northern Samangan Province.

In this context a legend recorded by Xuanzang refers to the first two lay disciples of Buddh, Trapus and Bhallik responsible for introducing Buddhism in that country. Originally these two were merchants of the kingdom of Balhik, as the name Bhalluk or Bhallik probably suggests the association of one with that country. They had gone to India for trade and had happened to be at Bodhgay when the Buddh had just attained enlightenment.

Just like the rest of Afghanistan, many historical sites in Kapis have been looted by smugglers and then sold abroad. During 2009 and 2010 twenty-seven relics were discovered by the National Security forces; these included ancient relics belonging to 2 BC and 4 BC mostly from Kohistan district.

Part 2 :

Kingdom of Kapis :

The Kingdom of Kapis (known in contemporary Chinese sources as Chinese: Caoguo and Chinese: Jibin) was a state located in what is now Afghanistan during the late 1st millennium CE. Its capital was the city of Kapis. The kingdom stretched from the Hindu Kush in the north to Bamiyan and Kandahar in the south and west, out as far as the modern Jalalabad District in the east.

The name Kapis appears to be a Sanskritized form of an older name for the area, from prehistory. Following its conquest in 329 BCE by Alexander the Great, the area was known in the Hellenic world as Alexandria on the Caucasus, although the older name appears to have survived.

In around 600 CE, the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang made a pilgrimage to Kapis, and described there the cultivation of rice and wheat, and a king of the Suli tribe. In his chronicle, he relates that in Kapis were over 6,000 monks of the Mahayana school of Buddhism. In a 7th-century Chinese chronicle, the Book of Sui, Kapis appears to be known as the kingdom of Cao (Chinese: Caoguo). In other Chinese works, it is called Jibin (Chinese: Jibin).

Between the 7th and 9th centuries, the kingdom was ruled by the Turk Shahi dynasty. At one point, Bagram was the capital of the kingdom, though in the 7th century, the center of power of Kapis shifted to Kabul.

Part 3 :

Kapis / Kapisi :

Statue of Buddha found in the monastery of Fondukistan, Gurband Valley, Parwan. VII century AD. Guimet Museum Kapisi (Kapisi, Chinese: Jiapishi) or Kapis was the capital city of the former Kingdom of Kapis (now part of modern Afghanistan). While the name of the kingdom has been used for the modern Kapis Province, the ancient city of Kapis was located in Parwan Province, in or near present-day Bagram.

The first references to Kapis appear in the writings of 5th-century BCE Indian scholar Achariya Panini. Panini refers to the city of Kapisi, a city of the Kapis kingdom. Panini also refers to Kapisyana, a famous wine from Kapis. The city of Kapisi also appeared as Kavisiye on Indo-Greek coins of Apollodotus/Eucratides, as well as the Nezak Huns.

Archeology discoveries in 1939 confirmed that the city of Kapis was an emporium for Kapisyana wine, discovering numerous glass flasks, fish-shaped wine jars, and drinking cups typical of the wine trade of the era. The grapes (Kapisyani Draksh) and wine (Kapisyani Madhu) of the area are referred to by several works of ancient Indian literature. The Mahabharat also noted the common practice of slavery in the city. The Begram ivories, inlays surviving from burnt furniture, were important artistic finds.

In later times, Kapis seems to have been part of a kingdom ruled by a Buddhist Kshatriya king holding sway over ten neighboring states including Lampak, Nagarahar, Gandhar and Banu, according to the Chinese pilgrim Xuan Zang who visited in 644 AD. Xuan Zang notes the Shen breed of horses from the area, and also notes the production of many types of cereals and fruits, as well as a scented root called Yu-kin.

Etymology

:

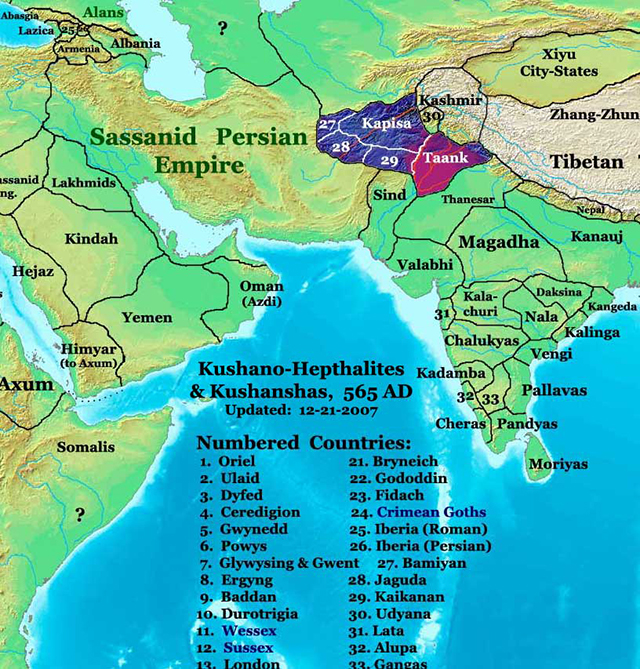

Asia in 565 AD, showing Kapis and its neighbors Scholar community holds that Kapis is equivalent to Sanskrit Kamboj. [excessive citations] In other words, Kamboj and Kapis are believed to be two attempts to render the same foreign word (which could not appropriately be transliterated into Sanskrit).Historian S. Levi further holds that old Persian Ka(m)bujiya or Kau(n)bojiya, Sanskrit Kamboj as well as Kapis, all etymologically refer to the same foreign word.

Even the evidence from the 3rd-century Buddhist tantra text Mahamayuri (which uses Kabush for Kapish) and the Ramayan-manjri by Sanskrit Acharya, Kshemendra of Kashmir (11th century AD), which specifically equates Kapis with Kamboj, thus substituting the former with the latter, therefore, sufficiently attest that Kapis and Kamboj are equivalent. Even according to illustrious Indian history series: History and Culture of Indian People, Kapis and Kamboj are equivalent. Scholars like Dr Moti Chandra, Dr Krishna Chandra Mishra etc. also write that the Karpasik (of Mahabharat) and Kapis (Ki-pin/Ka-pin/Chi-pin of the Chinese writings) are synonymous terms.

Thus, both Karpasik and Kapis are essentially equivalent to Sanskrit Kamboj. And Paninian term Kapisi is believed to have been the capital of ancient Kamboj. Kapis (Ki-pin, Ke-pin, Ka-pin, Chi-pin of the Chinese records), in fact, refers to the Kamboj kingdom, located on the south-eastern side of the Hindukush in the Paropamisadae region. It was anciently inhabited by the Asvakayan (Greek: Assakenoi), and the Asvayan (Greek Aspasio) (q.v.) sub-tribes of the Kambojs. Epic Mahabharat refers to two Kamboj settlements: one called Kamboj, adjacent to the Darads (of Gilgit), extending from Kafiristan to south-east Kashmir including Rajauri/Poonch districts, while the original Kamboj, known as Param Kamboj was located north of Hindukush in Transoxiana territory mainly in Badakshan and Pamirs/Allai valley, as neighbors to the Rishiks in the Scythian land. Even Ptolemy refers to two Kamboj territories/and or ethnics - viz.: (1) Tambyzoi, located north of Hindukush on Oxus in Bactria/Badakshan and (2) Ambautai located on southern side of Hindukush in Paropamisadae. Even the Komoi clan of Ptolemy, inhabiting towards Sogdian mountainous regions, north of Bactria, is believed by scholars to represent the Kamboj people.

With passage of time, the Paropamisan settlements came to be addressed as Kamboj proper, whereas the original Kamboj settlement lying north of Hindukush, in Transoxian, became known as 'Param-Kamboj' i.e. furthest Kamboj. Some scholars call Parama Kamboj as 'Uttara-Kamboj' i.e. northern Kamboj or Distant Kamboj. The Kapis-Kamboj equivalence also applies to the Paropamisan Kamboj settlement.

Physical

characteristics of the people of Kapis :

According to scholars, much of the description of the people from Kapis to Rajapur as given by Hiuen Tsang agrees well with the characteristics of the Kambojs described in the Buddhist text, Bhuridatta Jataka as well in the great Indian epic Mahabharat. Moreover, the Dron Parav of Mahabharat specifically attests that Rajapuram was a metropolitan city of the epic Kambojs. The Rajapuram (=Rajapur) of Mahabharat (Ho-b-she-pu-lo of Hiuen Tsang) has been identified with modern Rajauri in south-western Kashmir. Culturally speaking, Kapis had significant Iranian influence.

The

early Shahis of Kapis/Kabul :

While their ethnicities were probably mixed, they practiced both Buddhism and Hinduism like the rest of India The different scholars link their affinities to different ethnics. 11th-century Muslim histriographer Alberuni's confused accounts on the early history of Shahis based mainly as they are on folklore, do not inspire much confidence on the precise identity of the early Shahis of Kapis/Kabul. They call them as Hindus on the one hand and claim their descent from the Turks, while at the same time, they also claim their origin/descent from Tibet.

Dr V. A. Smith calls the early Shahis as a Cadet Branch of the Kushans without proof. H. M. Elliot identifies them with Kators/Katirs and further link them to Kushans. George Scott Robertson writes that the Kators/Katirs of Kafiristan belong to the Hindu Siyaposh tribal group of the Kams, Kamoz and Kamtoz tribes. Charles Fredrick Oldham identifies them with Nag-worshiping Takkas or Kathas and groups the Nag-cum-Sun worshipping Urasass (Hazaras), Abhisaras, Gandharas, Kambojs and Daradas collectively as the representatives of the Takkas or Kathas. Dr D. B. Pandey traces the affinities of the early Kabul Shahis to the Hunas. Bishan Singh and K. S. Dardi etc. connect the Kabul Shahis to the ancient Kshatriya clans of the Kambojs/Gandharas. 7th-century Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang, who visited INdis (629 AD - 645 AD) calls the ruler of Kapis as Buddhist and of a Kshatriya caste.

Kalhan, the 12th-century Kashmirian historian and author of the famous Rajatarangini, also calls the Shahis of Gandhar/Waihind as Kshatriyas. These early references from different sources link them as Kshatriya ruler and his dynasty undoubtedly to Hindu lineage. Further, though Kalhan takes the history of the Shahis to as early as or even earlier than 730 century AD [clarification needed], but he does not refer to any supplanting of the Shahi dynasty at any time in the entire history of the Shahis.

It is also worth mentioning here that the ancient Indian sources like Panini's Astadhyayi, Harivamsh, Vayu Puran, Manusmriti, Mahabharat, Kautiliya's Arthashastra, etc. call the Kambojs and the Gandhars as Kshatriyas. According to Olaf Caroe, the earlier Kabul Shahis, in some sense, were the inheritors of the Kushan-Hephthalite chancery tradition and had brought in more Hinduised form with time. There does not yet exist in the upper Kabul valley any documentary evidence or any identifiable coinage which can establish the exact affinities of these early Shahis who ruled there during the first two Islamic centuries.

Obviously, the affinities of the early Shahis of Kapis/Kabul are still speculative, and the inheritance of the Kushan-Hephthalite chancery tradition and political institutions by Kabul Shahis do not necessarily connect them to the preceding dynasty i.e. the Kushanas or Hephthalites. From the 5th century to about 794 AD, their capital was Kapis, the ancient home of the cis-Hindukush Kambojs – popularly also known as Ashvakas. After the Arab Moslems began raiding the Shahi kingdom, the Shahi ruler of Kapis moved their capital to Kabul (until 870 AD). Alberuni's accounts further claim that the last king of the early Shahiya dynasty was king Lagaturman (Katorman) who was overthrown and imprisoned by his Brahmin vizier called Kallar. Alberuni's reference to the Brahman vizier as having taken over the control of the Shahi dynasty, in fact, may be a reference to Kallar (and his successors) as having been followers of Brahmanical religion in contrast to Shahi Katorman (Lagaturman) or his predecessors Shahi rulers, who were undoubtedly staunch Buddhists. It is very likely that a change in religion may have been confused with change in dynasty. In any case, this started the line of so-called Hindu Shahi rulers, according to Alberuni's accounts.

Modern

ethnics of Kapis :

The Asvakayanas and Asvayanas are also believed to be sub-tribes of Paropamisan Kambojs, who were exclusively engaged in horse breeding/trading and also formed a specialised cavalry force.

Part 4 :

Kapish is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan.

Asia in 565 AD, showing Kapis and its neighbors Variants

of name :

Mention

by Panini :

Kapishyan is mentioned by Panini in Ashtadhyayi.

Kapishi is mentioned by Panini in Ashtadhyayi.

V S Agarwal mentions....Kapishi (IV.2.99) was a town known for its wine Kapishyan. According to Pliny Kapishi was destroyed by the Achaemenian emperor Cyrus (Kurush) in the sixth century B.C. It is identified with modern Begram, about 50 miles north of Kabul on the ground of a Kharoshthi inscription found there naming the city (Sten Konow, Ep. Ind,, VoL XXII (1933), p. 11).

History

:

Jat

Gotras after Kapis :

Scholars like Dr Moti Chandra, Dr Krishna Chandra Mishra, Dr J. L. Kamboj etc write that Karpasik of Mahabharat is same as Kapis or Ki-pin (or Ke-pin, Ka-pin, Chi-pin) of the Chinese records and represents the modern Kafiristan (now Nurestan)/Kohistan. The title of Kadphizes claimed by Kushan rulers when their power had spread from Kuei-shuang to Kaofu (Kambu) is also said to have derived from Kadphis (=Kapis). The Paninian Kapisi has been identified with modern Begram about 50 miles of north of Kabul on the ground that a Kharoshthi inscription naming the city has been found there. Al-Beruni refers to Kapis as Kayabish. Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang who visited Kapis in 644 AD calls it Kai-pi-shi(h). Hiuen Tsang describes Kai-pi-shi as a flourishing kingdom ruled by a Buddhist Kshatriya king holding sway over ten neighboring states including Lampak, Nagarahar, Gandhar and Banu etc. Till 9th century AD, Kapisi remained the second capital of the Shahi Dynasty of Kabul. Kapis (Chinese Ki-pin) is stated to have been earlier visited by lord Buddh in 6th c BCE. Ancient Kapis Janapada is related to the Kafiristan, south-east of the Hindukush. Kapis was known for goats and their skin. Hiuen Tsang talks of Shen breed of horses from Kapis (Kai-pi-shi) which in fact, was a Kamboj breed, since it was the latter which was always noted for its exceptional breed of horses. Further evidence from Hiuen Tsang shows that Kai-pi-shi produced all kind of cereals, many kinds of fruits, and a scented root called Yu-kin. The people used woolen and fur clothes and gold, silver and copper coins . Objects of merchandise from all parts were found here.

Visit

by Xuanzang 630 AD :

[p.19]: by snowy mountains, named Po-lo-si-na, and by black hills on the other three sides. The name of Polosina corresponds exactly with that of Mount Paresh or Aparasin of the 'Zend Avesta,' and with the Paropamisus of the Greeks, which included the Indian Caucasus, or Hindu Kush. Hwen Thsang further states, that to the north-west of the capital there was a great snowy mountain, with a lake on its summit, distant only 200 li, or about 33 miles. This is the Hindu Kush itself, which is about 35 miles to the north-west of Charikar and Opian ; but I have not been able to trace any mention of the lake in the few imperfect notices that exist of this part of Afghanistan.

The district of Capisene is first mentioned by Pliny, who states that its ancient capital, named Capisa, was destroyed by Cyrus. His copyist, Solinus, mentions the same story, but calls the city Caphusa, which the Delphine editors have altered to Capissa. Somewhat later, Ptolemy places the town of Kapis amongst the Paropamisadae, 2½ degrees to the north of Kabura or Kabul, which is nearly 2 degrees in excess of the truth. On leaving Bamian, in A.D. 630, the Chinese pilgrim travelled 600 li, or about 100 miles, in an easterly direction over snowy mountains and black hills (or the Koh-i-Baba and Paghman ranges) to the capital of Kiapishe or Kapisene. On his return from India, fourteen years later, he reached Kiapishe through Ghazni and Kabul, and left it in a north-east direction by the Panjshir valley towards Anderab. These statements fix the position of the capital at or near Opian, which is just 100 miles to the east of Bamian

[p.20]: by the route of the Hajiyak Pass and Ghorband Valley, and on the direct route from Ghazni and Kabul to Anderab. The same locality is, perhaps, even more decidedly indicated by the fact, that the Chinese pilgrim, on finally leaving the capital of Kapisene, was accompanied by the king as far as the town of Kiu-lu-sa-pang, a distance of one yojana, or about 7 miles to the north-east, from whence the road turned towards the north. This description agrees exactly with the direction of the route from Opian to the northern edge of the plain of Begram, which lies about 6 or 7 miles to the E.N.E. of Charikar and Opian. Begram itself I would identify with the Kiu-lu-sa-pang or Karsawan of the Chinese pilgrim, the Karsana of Ptolemy, and the Cartana of Pliny. If the capital had then been at Begram itself, the king's journey of seven miles to the north-east would have taken him over the united stream of the Panjshir and Ghorband rivers, and as this stream is difficult to cross, on account of its depth and rapidity, it is not likely that the king would have undertaken such a journey for the mere purpose of leave-taking. But by fixing the capital at Opian, and by identifying Begram with the Kiu-lu-sa-pang of the Chinese pilgrim, all difficulties disappear. The king accompanied his honoured guest to the bank of the Panjshir river, where he took leave of him, and the pilgrim then crossed the stream, and proceeded on his journey to the north, as described in the account of his life.

From all the evidence above noted it would appear certain that the capital of Kiapishe, or Kapisene, in the seventh century, must have been situated either at or near Opian. This place was visited by Masson,('Travels,' iii. 126.)

[p.21]: who describes it as "distinguished by its huge artificial mounds, from which, at various times, copious antique treasures have been extracted." In another place he notes that " it possesses many vestiges of antiquity ; yet, as they are exclusively of a sepulchral or religious character, the site of the city, to which they refer, may rather be looked for at the actual village of Malik Hupian on the plain below, and near Charikar." Masson writes the name Hupian, following the emperor Baber ; but as it is entered in "Walker's large map as Opiyan, after Lieutenant Leach, and is spelt Opian by Lieutenant Sturt, both of whom made regular surveys of the Koh-daman, I adopt the unaspirated reading, as it agrees better with the Greek forms of Opiai and Opiane of Hekataeus and Stephanus, and with the Latin form of Opianum of Pliny. As these names are intimately connected with that of the Paropamisan Alexandria, it will clear the way to further investigation, if we first determine the most probable site of this famous city.

The position of the city founded by Alexander at the foot of the Indian Caucasus has long engaged the attention of scholars ; but the want of a good map of the Kabul valley has been a serious obstacle to their success, which was rendered almost insurmountable by their injudicious alterations of the only ancient texts that preserved the distinctive name of the Caucasian Alexandria. Thus Stephanus describes it as being <greek>, " in Opiane, near India," for which Salmasius proposed to read Apiavvn. Again, Pliny describes it as Alexandriam Opianes,

[p.22]: which in the Leipsic and other editions is altered to Alexandri oppidum. I believe, also, that the same distinctive name may be restored to a corrupt passage of Pliny, where he is speaking of this very part of the country. His words, as given by the Leipsic editor, and as quoted by Cellarius, are "Cartana oppidum sub Caucaso, quod postea Tetragonis dictum. Hsec regie est ex adverse. Bactrianorum deinde cujus oppidum Alexandria, a conditore dictum." Both of the translators whose works I possess, namely Philemon Holland, A.D. 1601, and W. T. Riley, A.D. 1855, agree in reading ex adverso Bactrianorum. This makes sense of the words as they stand, but it makes nonsense of the passage, as it refers the city of Alexandria to Bactria, a district which Pliny had fully described in a previous chapter. He is speaking of the country at the foot of the Caucasus or Paropamisus ; and as he had already described the Bactrians as being " aversa mentis Paropamisi," he now uses almost the same terms to describe the position of the district in which Cartana was situated ; I would, therefore, propose to read " hsec regio est ex adverso Bactrise;" and as cujus cannot possibly refer to the Bactrians, I would begin the next sentence by changing the latter half of Bactrianorum in the text to Opiiorum ; the passage would then stand thus, " Opiorum (regio) deinde, cujus oppidum Alexandria a conditore dictum," — " Next the Opii, whose city, Alexandria, was named after its founder." But whether this emendation be accepted or not, it is quite clear from the other two passages, above quoted, that the city founded by Alexander at the foot of the Indian Caucasus was also

[p.23]: named Opiane. This fact being established, I will now proceed to show that the position of Alexandria Opiane agrees as nearly as possible with the site of the present Opian, near Charikar.

According to Pliny, the city of Alexandria, in Opiamim, was situated at 50 Roman miles, or 45.96 English miles, from Ortospana, and at 237 Roman miles, or 217.8 English miles, from Peucolaitis, or Pukkalaoti, which was a few miles to the north of Peshawar. As the position of Ortospana will be discussed in my account of the next province, I will here only state that I have identified it with the ancient city of Kabul and its citadel, the Bala Hisar. Now Charikar is 27 miles to the north of Kabul, which differs by 19 miles from the measurement recorded by Pliny. But as immediately after the mention of this distance he adds that " in some copies different numbers are found," I am inclined to read "triginta millia," or 30 miles, instead of " quinquaginta millia," which is found in the text. This would reduce the distance to 27½ English miles, which exactly accords with the measurement between Kabul and Opian. The distance between these places is not given by the Chinese pilgrim Hwen Thsang ; but that between the capital of Kiapishe and Pu-lu-sha-pu-lo, or Purushapura, the modern Peshawar, is stated at 600 + 100 + 500 = 1200 li, or just 200 miles according to my estimate of 6 li to the English mile. The last distance of 500 li, between Nagarahara and Purushawar, is certainly too short, as the earlier pilgrim. Fa Hian, in the beginning

[p.24]: of the fifth century, makes it 16 yojanas, or not less than 640 li, at 40 li to the yojana. This would increase the total distance to 1340 li, or 223 miles, which differs only by 5 miles from the statement of the Roman author. The actual road distance between Charikar and Jalalabad has not been ascertained, but as it measures in a direct line on Walker's map about 10 miles more than the distance between Kabul and Jalalabad, which is 115 miles, it may be estimated at 125 miles. This sum added to 103 miles, the length of road between Jalalabad and Peshawar, makes the whole distance from Charikar to Peshawar not less than 228 miles, which agrees very closely with the measurements recorded by the Roman and Chinese authors.

Pliny further describes Alexandria as being situated sub ipso Caucaso at the very foot of Caucasus," which agrees exactly with the position of Opian, at the northern end of the plain oi Kohdaman, or "hill-foot." The same position is noted by Curtius, who places Alexandria in radicibus montis, at the very base of the mountain. The place was chosen by Alexander on account of its favourable site at the tpioov or parting of the " three roads " leading to Bactria. These roads, which still remain unchanged, all separate at Opian, near Begram.

1. The north-east road, by the Panjshir valley, and over the Khawak Pass to Anderab.

2. The west road, by the Kushan valley, and over the Hindu Kush Pass to Ghori.

3. The south-west road, up the Ghorband valley, and over the Hajiyak Pass to Bamian.

[p.25]: The first of these roads was followed by Alexander on his march into Bactriana from the territory of the Paropamisadae. It was also taken by Timur on his invasion of India ; and it was crossed by Lieutenant Wood on his return from the sources of the Oxus. The second road must have been followed by Alexander on his return from Bactrian, as Strabo specially mentions that he took " over the same mountains another and shorter road" than that by which he had advanced. It is certain that his return could not have been by the Bamian route, as that is the longest route of all ; besides which, it turns the Hindu Kush, and does not cross it, as Alexander is stated to have done. This route was attempted by Dr. Lord and Lieutenant Wood late in the year, but they were driven back by the snow. The third road is the easiest and most frequented. It was taken by Janghez Khan after his capture of Bamian ; it was followed by Moorcroft and Burnes on their adventurous journeys to Balkh and Bokhara ; it was traversed by Lord and Wood after their failure at the Kushan Pass ; and it was surveyed by Sturt in A.D. 1840, after it had been successfully crossed by a troop of horse artillery.

Alexandria is not found in Ptolemy's list of the towns of the Paropamisadae ; but as his Niphanda, which is placed close to Kapis, may with a very little alteration be read as Ophianda, I think that we may perhaps recognize the Greek capital under this slightly altered form. The name of Opian is certainly as old as the fifth century B.C., as Hekataeus places a people called Opiai to the west of the upper course of the Indus. There is, however, no trace of this name in

[p.26]: the inscriptions of Darius, but we have instead a nation called Thatagush, who are the Sattagudai of Herodotus, and perhaps also the people of Si-pi-to-fa-la-sse of the Chinese pilgrim Hwen Thsang. This place was only 40 li, or about 7 miles, distant from the capital of Kiapishe, but unfortunately the direction is not stated. As, however, it is noted that there was a mountain named Aruna at a distance of 5 miles to the south, it is almost certain that this city must have been on the famous site of Begram, from which the north end of the Siah-koh, or Black Mountain, called Chehel Dukhtaran, or the " Forty Daughters," lies almost due south at a distance of 5 or 6 miles. It is possible, also, that the name of Tatarangzar, which Masson gives to the south-west corner of the ruins of Begram, may be an altered form of the ancient Thatagush, or Sattagudai. But whether this be so or not, it is quite certain that the people dwelling on the upper branches of the Kabul river must be the Thata-gush of Darius, and the Sattagudai of Herodotus, as all the other surrounding nations are mentioned in both authorities.

Part 5 :

Ancient Kingdom of Kapisa (500 BC) :

Asia in 565 AD, showing Kapis and its neighbors "....870 A.D. marks the first time that the Kingdom of Shambhala actually came under Moslem domination.".....The Dharma Fellowship was originally founded by personal request of His Holiness the 16th Karmapa, Rangjung Rigpe Dorje (1923-1981), "By 669 AD, the neighboring Turkish Shahi kingdoms of Kapisa (Shambhala) and Uddiyana were also both being hard pressed on their southwesterly flank by the inexorable expansion of the southern Arab Moslems."….....The Dharma Fellowship was originally founded by personal request of His Holiness the 16th Karmapa, Rangjung Rigpe Dorje (1923-1981)."

The earliest references to Kapisa appear in the writings of fifth century BCE Indian scholar Pa?ini. Pa?ini refers to the city of Kapisi, a city of the Kapisa kingdom, modern Bagram. Pa?ini also refers to Kapisayana, a famous wine from Kapisa. The city of Kapisi also appeared as Kavisiye on Graeco-Indian coins of Apollodotus I and Eucratides.....references to Kapisa appear in the writings of 5th century BCE Indian scholar Achariya Panini.

"According to the scholar Pliny, the city of Kapisi (also referred to as Kaphus by Pliny's copyist Solinus and Kapisene by other classical chroniclers) was destroyed in the sixth century BCE by the Achaemenid emperor Cyrus (Kurush) (559-530 BC). Based on the account of the Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang, who visited in AD 644, it seems that in later times Kapisa was part of a kingdom ruled by a Buddhist kshatriya king holding sway over ten neighboring states, including Lampak, Nagarahar, Gandhar, and Banu. Hiuen Tsang notes the Shen breed of horses from the area, and also notes the production of many types of cereals and fruits, as well as a scented root called Yu-kin.

Kapis is related to and included Kafiristan. Scholar community holds that Kapis is equivalent to Sanskrit Kamboj......Kapis (= Kapish), the ancient Sanskrit name of the region that included historic Kafiristan; which is also given as "Ki-pin" (or Ke-pin, Ka-pin, Chi-pin) in old Chinese chronicles. That name, unrelated to the Arabic word, is believed to have, at some point, mutated into the word Kapir. This linguistic phenomenon is not unusual for this region. The name of King Kanishaka, who once ruled over this region, is also found written as "Kanerik", an example of "s" or "sh" mutating to "r"....A number of legends about Kanishk, a great patron of Buddhism, were preserved in Buddhist religious traditions. Along with the Indian kings Ashok and Harshavardhan, and the Indo-Greek king Menander I (Milind), he is considered by Buddhists to have been one of the greatest Buddhist kings.

"Begram is the name of a village and a place in the Kapisa plain, about 50 km north of Kabul. It is also the name of a site that, just before World War II, delivered a fabulous treasure of art objects that became known worldwide. The treasure was composed of several hundred Greek and Roman objects originating from Alexandria, Egypt, hundreds of ivory objects originating from India, and several dozen Chinese lacquers. This treasure underlines the welcoming nature of ancient Afghanistan and the important role and power of the Kushan sovereigns who controlled the trade routes between the Near and Middle East, China, and India. It is also during this period that Buddhism flourished and was tolerated as one of the empire’s religions. As a result, the trade route also became a way through which pilgrims could travel safely in complete Kushan peace, which I have termed “Pax Kushana.”.... the royal city of Begram and the neighboring Buddhist monasteries such as Shotorak, Qol-e Nader, Koh- e Pahlawan, and, further away, Paitawa. However, we must keep in mind the excavations by Jules Barthoux, who unearthed the Buddhist site of Qaratcha, situated very close to the royal city of Begram. .....Other archaeological activity to consider is that of Roman Ghirshman, which took place during World War II. He proceeded with a stratigraphic excavation and unearthed three occupation periods of the capital, that used to serve as summer capital to the Kushan kings. According to Roman Ghirshman: Begram I corresponds to the period of the Indo-Greek domination, Begram II corresponds to the Kushan kings, and Begram III corresponds to the Kushano-Sassanid period and later the Hephtalites and Turcs who stayed until the Muslim invasion. In 1946, under the direction of Daniel Schlumberger, new DAFA director, Jacques Meunié undertook several excavations near the royal city’s door. Since then no other official missions have been undertaken on the site. However, recent studies conducted by Paul Bernard and myself attempt to prove that the Begram site should be identified as Alexandria under Caucasus."

Dharma Fellowship of His Holiness the 17th Gyalwa Karmapa, Urgyen Trinley Dorje......"In 672 an Arab governor of Sistan, Abbad ibn Ziyad, raided the frontier of Al-Hind and crossed the desert to Gandhar, but quickly retreated again. The marauder Obaidallah crossed the Sita River and made a raid on Kabul in 698 only to meet with defeat and humiliation. Vincent Smith, in Early History of India, states that the Turkishahiya dynasty continued to rule over Kabul and Gandhar up until the advent of the Saffarids in the ninth century. Forced by the inevitable advance of Islam on the west, they then moved their capital from Kapis to Wahund on the Indus, whence they continued as the Hindushahiya dynasty. This was in 870 A.D. and marks the first time that the KINGDOM OF SHAMBHALA actually came under Moslem domination. The Hindushahis recaptured Kabul and the rest of their Kingdom after the death of the conqueror Yaqub but never again maintained Kapisa as their capital."

In 642 A.D., a " King Ta-mo-yin-t'o-ho-szu" 3 of Uddiyan is said to have sent a gift of camphor and an embassy to the Emperor of China. This is the year that the Arabs succeeded in defeating the King of Kings, Yazdagird III, of Persia. The latter, fleeing eastward, met his death near Merv in 651. With the death of Yazdagird, last of the Sassanid dynasty, the southern bedouin hordes of Islam for the first time marched onto the soil of Iran and began their great, rapacious advance eastward. The kings of the Orient had cause to fear the coming of the Arabs. These southerners were savagely barbarian; a patchwork of desert tribes woven together by the threads of a fanatical monotheism and a religion which encouraged them to slay with the sword those whom they could not convert to their personal dominion. " Fight those who do not believe in Allah and the Last Day," says the Koran (Sura 9:29), " ...until they pay you tribute out of hand, having brought them low."

"The inexorable expansion of the Arabs spread along two fronts: the first moved through Nishapur to Herat, Merv and Balkh, reducing the northern provinces of Persia; the second passed south by way of Sistan (Sijistan) to the Helmand. In 650 Abdallah ibn Amr began the yet further push forwards across the desert of the Dasht-i-Lut. He was followed over the years by succeeding Moslem armies which, through continuous raids, massacres and looting, systematically transformed the wondrous flower-garden of Persian civilization and Mazdean or Buddhist culture into a scorched wasteland. Today all these lands lie under the yoke of Arabic culture."

"Moreover, although Mahayana had made advances into Afghanistan from Kashmir and Punjabi Gandhar during the fifth and sixth centuries, Xuanzang noted its presence only in Kapish and in the Hindu Kush regions west of Nagarhar. Sarvastivad remained the predominant Buddhist tradition of Nagarhar and northern Bactria."

Source :

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Kapisa_Province

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Kapisa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kapisi

https://www.jatland.com/home/Kapisha

http://balkhandshambhala.blogspot.com/ |