| SHATHPATH BRAHMAN Rishi

Yagnavalkya was the founder of Shukla Yajur Ved who was given

the knowledge of Yajurved by Lord Surya. Shukla Yajurved originally

had 15 Sakhas out of which only two sakhas or branches called

Madyandina and Kanva exist at present. Madyandina sakha is more

prevalent in North India where as Kanva Sakha is found mostly

in South India. Details of all the 15 Shakhas can be found in

the book Charana Vuyha Tantram.

Shathpath Brahman :

The Shatpath Brahman (Sanskrit: Shatpath Brahman, meaning 'Brahman of one hundred (shatam, cognate with Latin centum) paths', abbreviated to 'SB') is a commentary on the Sukla (white) YajurVed. Described as the most complete, systematic, and important of the Brahmans (commentaries on the Veds), it contains detailed explanations of Vedic sacrificial rituals, symbolism, and mythology.

Particularly in its description of sacrificial rituals (including construction of complex fire-altars), the Shatpath Brahman (SB) provides scientific knowledge of geometry (e.g. calculations of Pi and the root of the Pythagorean theorem) and observational astronomy (e.g. planetary distances and the assertion that the Earth is circular) from the Vedic period.

The Shatpath Brahman is also considered to be significant in the development of Vaishnavism as the origin of several Puranic legends and avatars of the Rig Vedic god Vishnu. Notably, all of them (Matsya, Kurma, Varah, Narsimha, and Vaman) are listed as the first five avatars in the Dashavatar (the ten principal avatars of Vishnu).

There are two versions (recensions) available of this text. They are the Madhyandina recension and the Kanva recension. This article focuses exclusively on the Madhyandina version of the Shatpath Brahman.

Nomenclature

:

•

'Brahman' means 'explanations of sacred knowledge or doctrine'.

Date

of Origin :

B. N. Narahari Achar also notes several other estimations, such as that of S.B. Dixit, D. Pingree, and N. Achar, in relation to a statement in the text that the Krittikas (the open star cluster Pleiades) never deviate from the east; Dixit's interpretation of this statement to mean that the Krittikas rise exactly in the east, and calculated that the Krittikas were on the celestial equator at about 3000 BCE, is a subject of debate between the named scholars; Pingree rejects Dixit’s arguments.

S.C. Kak states that a 'conservative chronology places the final form of the Shatpath Brahman to 1000-800 B.C.E... [although on] the other hand, it is accepted that the events described in the Veds and the Brahmans deal with astronomical events of the 4th millennium [i.e. 3,000] B.C.E. and earlier'. According to Kak, the Shatpath Brahman itself contains astronomical references dated by academics such as P.C. Sengupta 'to c. 2100 B.C.E', and references the drying up of the Sarasvati river, believed to have occurred around 1900 B.C.E.

Sanskrut :

tarhi videgho mathava asa | sarasvatyam sa tata eva prandahannabhiyayemam prthivim tam gotamasca rahugano videghasca mathava? pascaddahantamanviyatuh sa imah sarva nadiratidadaha sadaniretyuttaradgirernirghavati tam haiva natidadaha tam ha sma tam pura brahmana na tarantyanatidagdhagnina vaisvanareneti

Shatpath Brahmnana, transliteration of Khand I, Adhyâya IV, Brâhmana I, Verse 14

English Translation :

Mâthava, the Videgha, was at that time on the (river) Sarasvatî. He (Agni) thence went burning along this earth towards the east; and Gotama Râhûgana and the Videgha Mâthava followed after him as he was burning along. He burnt over (dried up) all these rivers. Now that (river), which is called 'Sadânîrâ,' flows from the northern (Himâlaya) mountain: that one he did not burn over. That one the Brâhmans did not cross in former times, thinking, 'it has not been burnt over by Agni Vaisvânara.'

Shatpath Brahman, English Translation by Julius Eggeling (1900), Khand I, Adhyâya IV, Brâhmana I, Verse 14

Scholars have extensively rejected Kak's arguments; Witzel criticizes Kak for "faulty reasoning" and taking "a rather dubious datum and using it to reinterpret Vedic linguistic, textual, ritual history while neglect[ing] all the other contradictory data." According to Witzel, the Shatpath Brahman does not contain precise contemporary astronomical records, but rather only approximate naked-eye observations for ritual concerns which likely reflect oral remembrances of older time periods; furthermore, the same general observations are recorded in the Babylonian MUL.APIN tablets of c. 1000 BCE. The Shatpath Brahman contains clear references to the use of iron, so it cannot be dated earlier than c. 1200-1000 BCE, while it reflects cultural, philosophical, and socio-political developments that are later than other Iron Age texts (such as the Atharv Ved) and only slightly earlier than the time of the Buddh (c. 5th century BCE).

The Madhyandina recension is known as the Vajasaneyi madhyandina sakha, and is ascribed to Yajñavalkya Vajasaneya.

The Kanva recension is known as the Kanva sakha, and is ascribed to Samkar.

Scholars have extensively rejected Kak's arguments; Witzel criticizes Kak for "faulty reasoning" and taking "a rather dubious datum and us[ing] it to reinterpret Vedic linguistic, textual, ritual history while neglect[ing] all the other contradictory data." According to Witzel, the Shatpath Brahman does not contain precise contemporary astronomical records, but rather only approximate naked-eye observations for ritual concerns which likely reflect oral remembrances of older time periods; furthermore, the same general observations are recorded in the Babylonian MUL.APIN tablets of c. 1000 BCE. The Shatpath Brahman contains clear references to the use of iron, so it cannot be dated earlier than c. 1200-1000 BCE, while it reflects cultural, philosophical, and socio-political developments that are later than other Iron Age texts (such as the Atharv Ved) and only slightly earlier than the time of the Buddha (c. 5th century BCE).

The 14 books of the Madhyandina recension can be divided into two major parts. The first 9 books have close textual commentaries, often line by line, of the first 18 books of the corresponding samhita of the Sukla (white) Yajur Ved. The remaining 5 books of the Shatpath cover supplementary and ritualistically newer material; the content of the 14th and last book constitutes the Brhad-Aranyaka Upanishad. The IGNCA also provides further structural comparison between the recensions, noting that the 'names of the Khands also vary between the two (versions) and the sequence in which they appear':

The IGNCA adds that 'the division of Kandika is more rational in the Kanva text than in the other... The name 'Shatpath', as Eggeling has suggested, might have been based on the number of Adhyayas in the Madhyandina which is exactly one hundred. But the Kanva recension, which has one hundred and four Adhyayas is also known by the same name. In Indian tradition words like 'sata' and 'sahasra', indicating numbers, do not always stand for exact numbers'.

Brihadaranayaka

Upanishad :

Significance in Science :

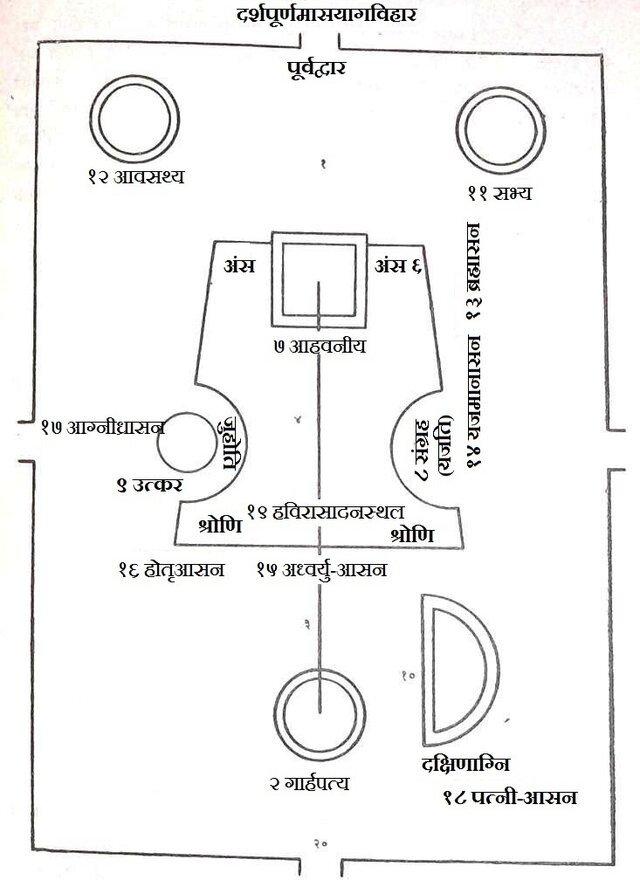

Shape of fire altar during full moon-new moon sacrifice Geometry and mathematics of the Shatpath Brahman and the Sulhasutras are generally considered [to be] the description of the earliest science in India... Specifically, the development of the scientific method in India in that age was inspired by some rough parallels between the physical universe and man's physiology [i.e. correspondence or equivalence between the macrocosm and microcosm]. This led to the notion that if one could understand man fully, that would eventually lead to the understanding of the universe... This led to a style of seeking metaphors to describe the unknown, which is the first step in the development of a scientific theory. A philosophy of the scientific method is already sketched in the RgVed. According to the RgVedic sages, nature has immutable laws and it is knowable by the mind...

—

Astronomy of the Shatpath Brahman by Subhash C.

Kak, Indian Journal of History of Science, 28(1),

1993

In relation to sacrifice and astronomical phenomena detailed in texts such as the Shatpath Brahman (e.g. sacrifices performed during the waxing and waning of the moon), N. Aiyangar states the fact that 'the Vedic people had a celestial [i.e. astronomical] counterpart of their sacrificial ground is clear', and cites an example of the Yajna Varah sacrifice in relation to the constellation of Orion.[20] Roy elaborates further on this example, stating that when 'the sun became united with Orion at the vernal equinox...[this] commenced the yearly [YajnaVarah] sacrifice'. The vernal (March) equinox marks the onset of spring, and is celebrated in Indian culture as the Holi festival (the spring festival of colours).

I.G. Pearce states that the Shatpath Brahman - along with other Vedic texts such as the Veds, Samhitas, and Tattiriya Samhita - evidences 'the astronomy of the Vedic period which, given very basic measuring devices (in many cases just the naked eye), gave surprisingly accurate values for various astronomical quantities. These include the relative size of the planets the distance of the earth from the sun, the length of the day, and the length of the year'. A.A. Macdonell adds that the Shatpath in particular is notable as - unlike the Samhitas - in it the Earth was 'expressly called circular (parimandala)'.

Mathematics :

A miniature replica of the Falcon altar (with yajna utensils) used during Athirathram

Layout

of a basic domestic fire altar

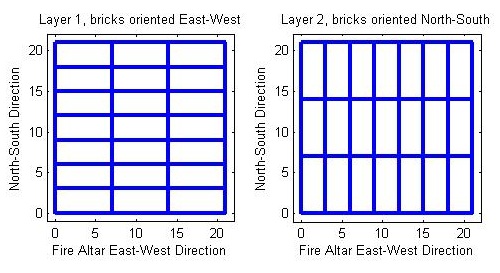

In the construction of fire altars used for sacrifices, Kak also notes the importance of the number, configuration, measurements, and patterns of bricks representing factors such as :

•

Vedic Meters : The rhythmic structure of verses

in sacred utterances or mantras, particularly from

the Rig Ved

—

Rig Ved (translated by R.T.H. Griffith, 1896), Book

10, Hymn 90, Verse 1

Vedic geometry is attached to ritual because it is concerned with the measurement and construction of ritual enclosures [and] of altars... Vedic geometry developed from the construction of these and other complex altar shapes. All are given numerous interpretations in the Brahmans and Aranyakas [texts relating to the Veds]... [but the] Sulba Sutras contain the earliest extant verbal expression of the closely related theorem that is still often referred to as the Theorem of Pythagoras but that was independently discovered by the Vedic Indians... —

Discovering the Veds: Origins, Mantras, Rituals,

Insights by Frits Staal, 2008 (pp. 265-267)

As a result of the mathematics required for the construction of these altars, many rules and developments of geometry are found in Vedic works. These include :

Use of geometric shapes, including triangles,

—

Mathematics in the service of religion: I. Veds

and Vedngas, by I.G. Pearce (School of Mathematics

and Statistics University of St Andrews, Scotland)

Sanskrut :

pañcadasatmano'kuruta

astacatvarimsadistakantsa naiva vyapnot

- Shatpath Brahman, transliteration of Khand X, Adhyâya IV, Brahmana II, Verses 13-18

English Translation :

He

made himself fifteen bodies of forty-eight bricks

each: he did not succeed. [15x48=720]

- Shatpath Brahman, English Translation by Julius Eggeling (1900), Khand X, Adhyâya IV, Brahmana II, Verses 13-18

Significance in Vaishnavism :

A.A. Macdonell, A.B. Keith, J. Roy, J. Dowson, W.J. Wilkins, S. Ghose, M.L. Varadpande, N Aiyangar, and D.A. Soifer all state that several avatars and associated Puranic legends of Vishnu either originate (e.g. Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, and Narasimha) or at least were significantly developed (e.g. Vamana) in the Satapatha Brahmana (SB). Notably, all constitute the first five avatars listed in the Dashavatar, the ten principal avatars of Vishnu.

Vishnu

:

Khand

14, Adhyaya 1, Brahman 1 :

Kurma

:

Eggeling adds that the 'kapals [cups used in ritual sacrifices] are usually arranged in such a manner as to produce a fancied resemblance to the (upper) shell of the tortoise, which is a symbol of the sky, as the tortoise itself represents the universe... In the same way the term kapala, in the singular, is occasionally applied to the skull, as well as to the upper and the lower case of the tortoise, e.g. Sat Br. VII, 5, 1, 2 [7.5.1.2].'

Khand 1, Adhyaya 6, Brahman 2 :

Sanskrut :

tercantah

sramyantasceruh | sramena ha sma vai taddeva jayanti

yadesamvjayyamasarsayasca tebhyo deva vaiva prarocayam

cakruh svayam vaiva dadhrire pretavtadesyamo yato

devah svargam lokam samasnuvateti te kim prarocate

kim prarocata iti ceruretpurodasameva kurmam bhutva

sarpanta? teha sarva eva menire ya? vai yajña

iti

- Shatpath Brahmnan, transliteration of Khand I, Adhyâya VI, Brâhman II, Verses 3-4

English Translation :

They

went on praising and toiling; for by (religious)

toil, the gods indeed gained what they wished

to gain, and (so did) the Rishis.

Now whether it be that the gods caused it (the

sacrifice) to attract (or, peep forth to) them,

or whether they took to it of their own accord,

they said, 'Come, let us go to the place whence

the gods obtained possession of the world of heaven!'

They went about saying (to one another), 'What

attracts? What attracts?' and came upon the sacrificial

cake which had become a tortoise and was creeping

about. Then they all thought, 'This surely must

be the sacrifice!'

- Shatpath Brahman, English Translation by Julius Eggeling (1900), Khand I, Adhyâya VI, Brâhman II, Verses 3-4

Macdonell also notes another instance in the Taittiriya Samhita (2.6.3; relating to the Krishna (Black) Yajur Ved), where Prajapati assigns sacrifices for the gods and places the oblation within himself, before Risis arrive at the sacrifice and 'the sacrificial cake (purodas) is said to become a tortoise'.

Khand 6, Adhyaya 1, Brahman 1 :

Sanskrut :

so

'yam purusah prajapatirakamayata bhuyantsyam prajayeyeti

so 'sramyatsa tapo 'tapyata sa srantastepano brahmaiva

prathamamasrjata trayomeva vidyam saivasmai pratisthabhavattasmadahurbrahmasya

sarvasya pratistheti tasmadanucya pratitisthati

pratistha hyesa yadbrahma tasyam pratisthayam

pratisthito 'tapyata

- Shatpath Brahmnan, transliteration of Khand VI, Adhyâya I, Brâhman I, Verses 8-10 and 12

English Translation :

Now

this Person Pragâpati desired,

'May I be more (than one), may I be reproduced!'

He toiled, he practised austerity. Being worn

out with toil and austerity, he created first

of all the Brahman (neut.), the triple science.

It became to him a foundation: hence they say,

'the Brahman (Ved) is the foundation of everything

here.' Wherefore, having studied (the Ved) one

rests on a foundation; for this, to wit, the Ved,

is his foundation. Resting on that foundation,

he (again) practised austerity.

- Shatpath Brahman, English Translation by Julius Eggeling (1900), Khand VI, Adhyâya I, Brâhmana I, Verses 8-10 and 12

Vak (speech) is female (e.g. SB 1.2.5.15, 1.3.3.8, 3.2.1.19, 3.2.1.22). Used in ritual sacrifices, so is the sacrificial altar (Vedi; SB 3.5.1.33, 3.5.1.35), the spade (abhri; SB 3.5.4.4, 3.6.1.4, 3.7.1.1, 6.3.1.39; see section on Varah, below), and the firepan (ukha; SB 6.6.2.5). The (generative) principle of gender (i.e. male and female coupling to produce something) is pervasive throughout (as reflected by the Sanskrit language itself).

Khand 7, Adhyaya 5, Brahman 1 :

Sanskrut :

kurmamupadadhati

| raso vai kurmo rasamevaitadupadadhati yo vai

sa esam lokanamapsu praviddhanam paranraso 'tyaksaratsa

esa kurmastamevaitadupadadhati yavanu vai rasastavanatma

sa esa ima eva lokah

- Shatpath Brahman, transliteration of Khand VII, Adhyâya V, Brâhman I, Verses 1-2 and 6

English Translation :

He

then puts down a (living) tortoise;--the tortoise

means life-sap: it is life-sap (blood) he thus

bestows on (Agni). This tortoise is that life-sap

of these worlds which flowed away from them when

plunged into the waters: that (life-sap) he now

bestows on (Agni). As far as the life-sap extends,

so far the body extends: that (tortoise) thus

is these worlds.

- Shatpath Brahman, English Translation by Julius Eggeling (1900), Khand VII, Adhyâya V, Brâhman I, Verses 1-2 and 6

Originally a form of Prajapati, the creator-god, the tortoise is thus clearly and directly linked with Vedic ritual sacrifice, the sun, and with Kasyapa as a creator (or progenitor). The tortoise is also stated to represent the three worlds (i.e. the triloka). SB 5.1.3.9-10 states 'Pragapati (the lord of generation) represents productiveness... the male means productiveness'. SB 14.1.1, which relates the story of Vishnu becoming the greatest of the gods at a sacrifice of the gods before being decapitated by His bow, states the head of Vishnu became the sun when it fell.

Matsya

:

Sanskrut :

manave

ha vai pratah | avanegyamudakamajahruryathedam panibhyamavanejanayaharantyevam

tasyavanenijanasya matsyah pani apede

- Shatpath Brahman, transliteration of Khand I, Adhyaya VIII, Brahman I ('The Ida'), Verses 1-4

English Translation :

In

the morning they brought to Manu water

for washing, just as now also they (are wont to)

bring (water) for washing the hands. When he was

washing himself, a fish came into his hands.

- Shatpath Brahman, English Translation by Julius Eggeling (1900), Khand I, Adhyaya VIII, Brahman I ('The Ida'), Verses 1-4

Aiyangar explains that, in relation to the Rig Ved, 'Sacrifice is metaphorically called [a] Ship and as Manu means man, the thinker, [so] the story seems to be a parable of the Ship of Sacrifice being the means for man's crossing the seas of his duritas, [meaning his] sins, and troubles'. SB 13.4.3.12 also mentions King Matsya Sammad, whose 'people are the water-dwellers... both fish and fishermen... it is these he instructs; - 'the Itihas is the Ved'.'

Narsimha

:

By means of the Surâ-liquor Namuki, the Asura, carried off Indra's (source of) strength, the essence of food, the Soma-drink. He (Indra) hasted up to the Ashvins and Sarasvatî, crying, 'I have sworn to Namuki, saying, "I will slay thee neither by day nor by night, neither with staff nor with bow, neither with the palm of my hand nor with the fist, neither with the dry nor with the moist!" and yet has he taken these things from me: seek ye to bring me back these things!

—

Shatpath Brahman, translated by Julius Eggeling

(1900), Khand XII, Adhyaya VII, Brahman III, Verse

1

Sanskrut :

tvam jaghantha namucim makhasyum dasam krnvana rsayevimayam |

- Rig Ved transliteration of Book 10, Hymn 73, Verse 7

English English Translation :

War-loving Namuci thou smotest, robbing the Dasa of his magic for the Rishi.

- Rig Ved English Translation by Ralph T.H. Griffith (1896) of Book 10, Hymn 73, Verse 7

Vaman

:

Khand I, Adhyaya 2, Brahman 5 :

Sanskrut :

devasca

va asurasca | ubhaye prajapatyah pasprdhire tato

deva anuvyamivasuratha hasura menire 'smakameVedm

khalu bhuvanamiti

- Shatpath Brahman, transliteration of Khand I, Adhyaya II, Brahman V, Verses 1-5

English Translation :

The gods and

the Asurs, both of them sprung from Prajapati,

were contending for superiority. Then the gods were

worsted, and the Asuras thought: 'To us alone assuredly

belongs this world!

- Shatpath Brahman, English Translation by Julius Eggeling (1900), Khand I, Adhyaya II, Brahman V, Verses 1-5

Eggeling notes that in the Shatpath Brahman, 'we have here the germ [i.e. origin] of the Dwarf incarnation of Vishnu'.[56] The difference in this account - aside from no mention of Bali - is that instead of gaining the earth by footsteps, it is gained by as much as Vaman can lie upon as a sacrifice. That this legend developed into Vaman taking three steps, as noted by Aiyangar, originates from the three strides of Vishnu covering the three words in the RigVed (1.22 and 1.154). Notably, the three steps of Vishnu are mentioned throughout the Shatpath Brahman as part of the sacrificial rituals described (e.g. SB 1.9.3.12, 5.4.2.6, and 6.7.4.8).

Khand

6, Adhyaya 7, Brahman 4 :

Sanskrut :

sa vai visnukramankrantva | atha tadanimeva vatsaprenopatisthate yatha prayayatha tadanimeva vimuñcettadrktaddevanam vai vidhamanu manusyastasmadu hedamuta manuso gramah prayayatha tadanimevavasyati

- Shatpath Brahman, transliteration of Khand VI, Adhyaya VII, Brahman IV, Verse 8

English Translation :

And, again, why the Vishnu-strides and the Vâtsapra rite are (performed). By the Vishnu-strides Prajapati drove up to heaven. He saw that unyoking-place, the Vâtsapra, and unyoked thereat to prevent chafing; for when the yoked (beast) is not unloosed, it is chafed. In like manner the Sacrificer drives up to heaven by the Vishnu-strides; and unyokes by means of the Vâtsapra.

- Shatpath Brahman, English Translation by Julius Eggeling (1900), Khand VI, Adhyaya VII, Brahman IV, Verse 8

Varah

:

Khand 14, Adhyaya 1, Brahman 2 :

Sanskrut :

atha Varahvihatam iyatyagra asiditiyati ha va iyamagre prthivyasa pradesamatri tamemusa iti Varah ujjaghana so'syah patih prajapatistenaivainametanmithunena priyena dhamna samardhayati krtsnam karoti makhasya te'dya siro radhyasam devayajane prthivya makhaya tva makhasya tva sirsna ityasaveva bandhuh

- Shatpath Brahman, transliteration of Khand XIV, Adhyaya I, Brahman II ('The making of the pot'), Verse 11

English Translation :

Then (earth) torn up by a boar (he takes), with 'Only thus large was she in the beginning,'--for, indeed, only so large was this earth in the beginning, of the size of a span. A boar, called Emûsha, raised her up, and he was her lord Prajapati: with that mate, his heart's delight, he thus supplies and completes him;--'may I this day compass for you Makha's head on the Earth's place of divine worship: for Makha thee! for Makha's head thee!'

- Shatpath Brahman, English Translation by Julius Eggeling (1900), Khand XIV, Adhyaya I, Brahman II ('The making of the pot'), Verse 11

The context of this verse is in relation to a Pravargya ritual, where clay/earth is dug up, fashioned or 'spread out' into Mahâvîra pots (symbolising the head of Vishnu), and baked in a fire altar (an explanation of Vishnu's decapitation relating to this ritual is given in SB 14.1.1). S. Ghose states that the 'first direct idea of the boar as an incarnation of Vishnu performing the specific task of rescuing the earth is mentioned in the Shatpath Brahman... the nucleus of the story of the god rescuing the earth in the boar-shape is found here'. A.B. Keith states that the boar 'is called Emusa [or 'Emûsha' in the SB] from its epithet emusa, [meaning] fierce, in the Rig Ved'. However, as this name occurs only once in the Rig Ved, the ascribed meaning cannot be verified:

10 All these things Vishnu brought, the Lord of ample stride whom thou hadst sent -

— Rig Ved (translated by R.T.H. Griffith, 1896), Book 8, Hymn 66, Verse 10

Khand 5, Adhyaya 4, Brahman 3 :

Sanskrut :

deva

ghrtakumbham pravesayam cakrustato Varahh sambabhuva

tasmadvaraho meduro ghrtaddhi sambhutastasmadvarahe

gavah samjanate svamevaitadrasamabhisamjanate tatpasunamevaitadrase

pratitisthati tasmadvarahya upanaha upamuñcate

- Shatpath Brahman, transliteration of Khand V, Adhyaya IV, Brahman III, Verses 19-20

English Translation :

He

then puts on shoes of boar’s skin. Now the

gods once put a pot of ghee on the fire.

There from a boar was produced: hence the boar is

fat for it was produced from ghee. Hence also cows

readily take to a boar: it is indeed their own essence

(life-sap, blood) they are readily taking to. Thus

he firmly establishes himself in the essence of

the cattle: therefore he puts on shoes of boar’s

skin.

- Shatpath Brahman, English Translation by Julius Eggeling (1900), Khand V, Adhyaya IV, Brahman III, Verses 19-20

The form of a boar was produced from a sacrificial oblation of the gods, and boars share the essence of cattle (which symbolise prosperity and sacrifice in SB 3.1.4.14, and productiveness in 5.2.5.8). Eggeling notes that in this ceremony, the King wears boar-boots to engage in a mock-battle with a Raganya (a Kshatriya noble or royal), stated to be 'Varun's consecration; and the Earth is afraid of him'. This ritual therefore seems to be significant as the mock-battle between the King (symbolising the boar) and the Raganya (symbolising Varun, Rig Vedic deity of water) parallels the battle between Varah with the Asur Hiranyaksa in various Puranic accounts of the Earth being saved and lifted out of the waters.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |