| STELE

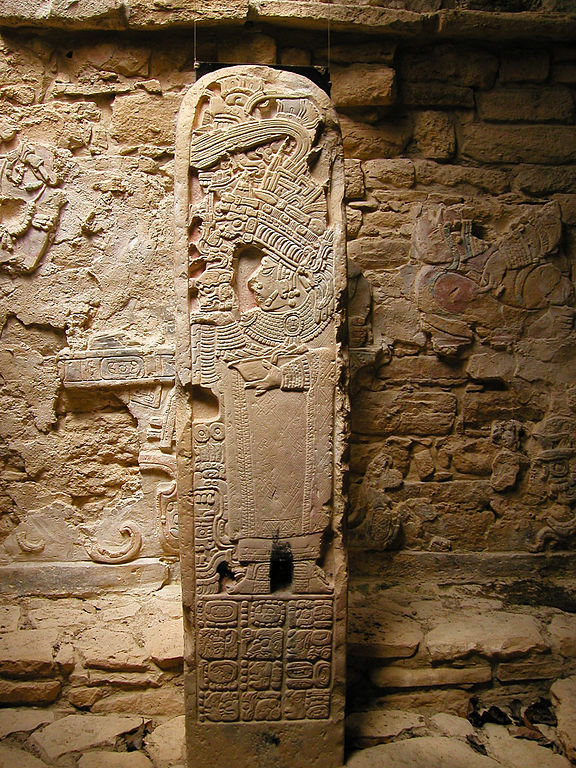

Stele N from Copán, Honduras, depicting King K'ac Yipyaj Chan K'awiil ("Smoke Shell"), as drawn by Frederick Catherwood in 1839

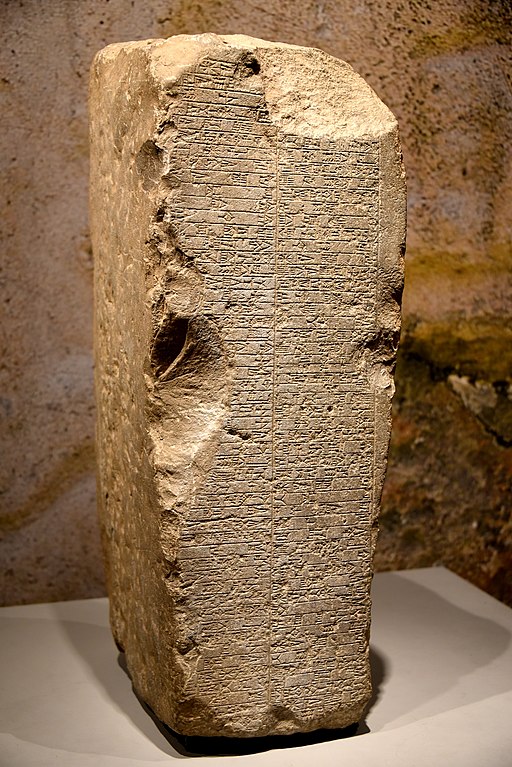

Stele to the French 8th Infantry Regiment. One of more than half a dozen steles located on the Waterloo battlefield. A stele (STEE-lee), or occasionally stela (plural stelas or stelæ), when derived from Latin, is a stone or wooden slab, generally taller than it is wide, erected in the ancient world as a monument. The surface of the stele often has text, ornamentation, or both. These may be inscribed, carved in relief, or painted.

Stelae were created for many reasons. Grave stelae were used for funerary or commemorative purposes. Stelae as slabs of stone would also be used as ancient Greek and Roman government notices or as boundary markers to mark borders or property lines. Stelae were occasionally erected as memorials to battles. For example, along with other memorials, there are more than half-a-dozen steles erected on the battlefield of Waterloo at the locations of notable actions by participants in battle.

Traditional Western gravestones may technically be considered the modern equivalent of ancient stelae, though the term is very rarely applied in this way. Equally, stele-like forms in non-Western cultures may be called by other terms, and the words "stele" and "stelae" are most consistently applied in archaeological contexts to objects from Europe, the ancient Near East and Egypt, China, and sometimes Pre-Columbian America.

History :

The funerary stele of Thrasea and Euandria, c. 365 BC Steles have also been used to publish laws and decrees, to record a ruler's exploits and honors, to mark sacred territories or mortgaged properties, as territorial markers, as the boundary steles of Akhenaton at Amarna, or to commemorate military victories. They were widely used in the ancient Near East, Mesopotamia, Greece, Egypt, Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and, most likely independently, in China and elsewhere in the Far East, and, independently, by Mesoamerican civilisations, notably the Olmec and Maya.

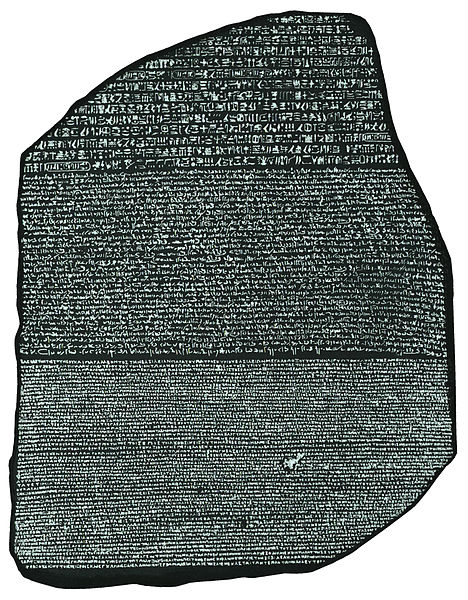

The large number of steles, including inscriptions, surviving from ancient Egypt and in Central America constitute one of the largest and most significant sources of information on those civilisations, in particular Maya stelae. The most famous example of an inscribed stela leading to increased understanding is the Rosetta Stone, which led to the breakthrough allowing Egyptian hieroglyphs to be read. An informative stele of Tiglath-Pileser III is preserved in the British Museum. Two steles built into the walls of a church are major documents relating to the Etruscan language.

Standing stones (menhirs), set up without inscriptions from Libya in North Africa to Scotland, were monuments of pre-literate Megalithic cultures in the Late Stone Age. The Pictish stones of Scotland, often intricately carved, date from between the 6th and 9th centuries.

An obelisk is a specialized kind of stele. The Insular high crosses of Ireland and Britain are specialized steles. Totem poles of North and South America that are made out of stone may also be considered a specialized type of stele. Gravestones, typically with inscribed name and often with inscribed epitaph, are among the most common types of stele seen in Western culture.

Most recently, in the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin, the architect Peter Eisenman created a field of some 2,700 blank steles. The memorial is meant to be read not only as the field, but also as an erasure of data that refer to memory of the Holocaust.

Egypt :

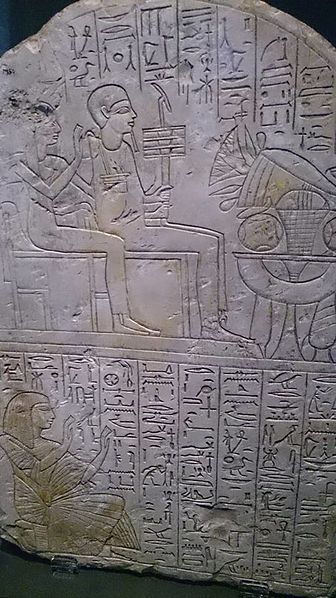

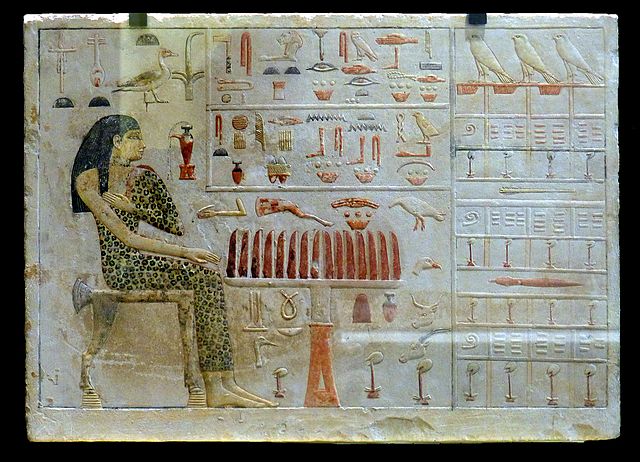

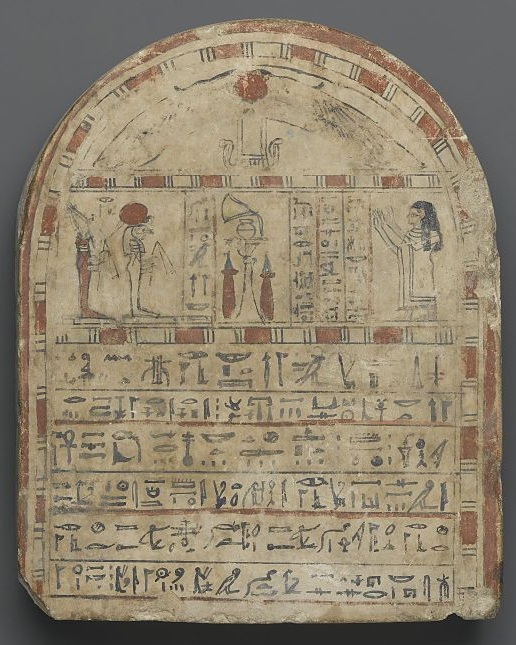

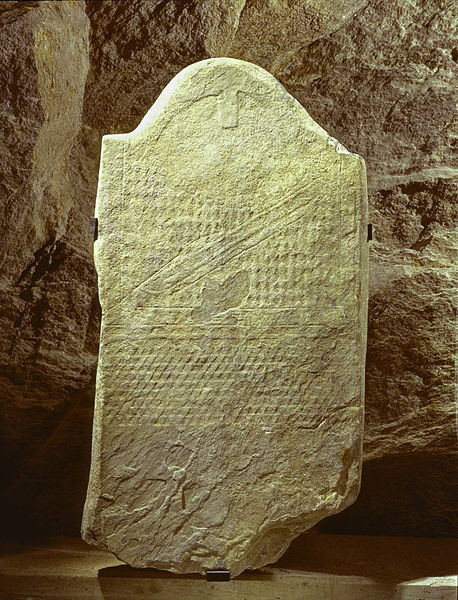

Egyptian hieroglyphs on an Egyptian funerary stela in Manchester Museum Egyptian steles (or Stelae, Books of Stone) have been found dating as far back as the First Dynasty of Egypt. These vertical slabs of stone are used as tombstones, for religious usage, and to mark boundaries, and are most commonly made of limestone and sandstone, or harder kinds of stone such as granite or diorite, but wood was also used in later times.

Stele fulfilled several functions. There were votive, commemorative, and liminal or boundary stelae, but the largest group was the tomb stelae. Their picture area showed the owner of the stele, often with his family, and an inscription listed the name and titles of the deceased after a prayer to one, or several, of the gods of the dead and request for offerings. Less frequently, an autobiographical text provided additional information about the individuals life.

In the mastaba tombs of the Old Kingdom (2686 - 2181 BC), stelae functioned as false doors, symbolizing passage between the present and the afterlife, which allowed the deceased to received offerings. These were both real and represented by formulae on the false door.

Liminal, or boundary, stele were used to mark size and location of fields and the country's borders. Votive stelae were exclusively erected in temples by pilgrims to pay homage to the gods or sacred animals. Commemorative stelae were placed in temples by the pharaoh, or his senior officials, detailing important events of his reign. Some of the most widely known Egyptian stelae include: the Kamose Stelae, recounting the defeat of the Hyksos; the Victory Stele, describing the campaigns of the Nubian pharaoh Piye as he reconquered the country; the Restoration Stele of Tutankhamun (1336 - 1327 BC), detailing the religious reforms enacted after the Amarna period; and the Merneptah Stele, which features the first known historical mention of the Israelites. In Ptolemaic times (332 - 30 BC), decrees issued by the pharaoh and the priesthood were inscribed on stelae in hieroglyphs, demotic script and Greek, the most famous example of which is the Rosetta Stone.

Urartu

:

Greece :

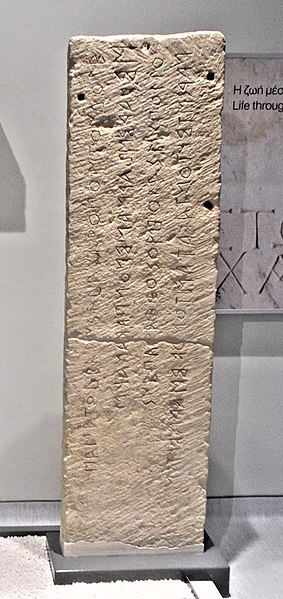

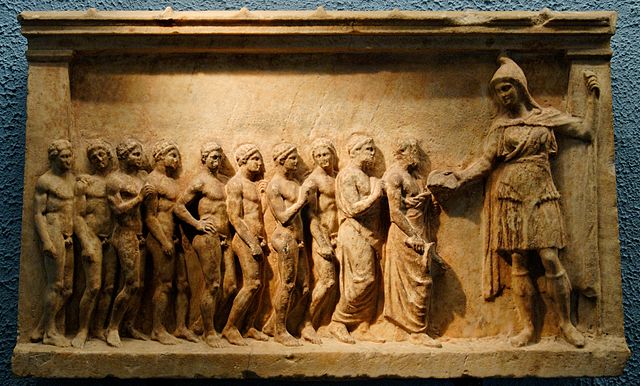

Stele of Arniadas at the Archaeological Museum of Corfu Greek funerary markers, especially in Attica, had a long and evolutionary history in Athens. From public and extravagant processional funerals to different types of pottery used to store ashes after cremation, visibility has always been a large part of Ancient Greek funerary markers in Athens. Regarding stelai (Greek plural of stele), in the period of the Archaic style in Ancient Athens (600 BC) stele often showed certain archetypes of figures, such as the male athlete. Generally their figures were singular, though there are instances of two or more figures from this time period. Moving into the 6th and 5th centuries BC, Greek stelai declined and then rose in popularity again in Athens and evolved to show scenes with multiple figures, often of a family unit or a household scene. One such notable example is the Stele of Hegeso. Typically grave stelai are made of marble and carved in relief, and like most Ancient Greek sculpture they were vibrantly painted. For more examples of stelai, the Getty Museum's published Catalog of Greek Funerary Sculpture is a valuable resource.

China :

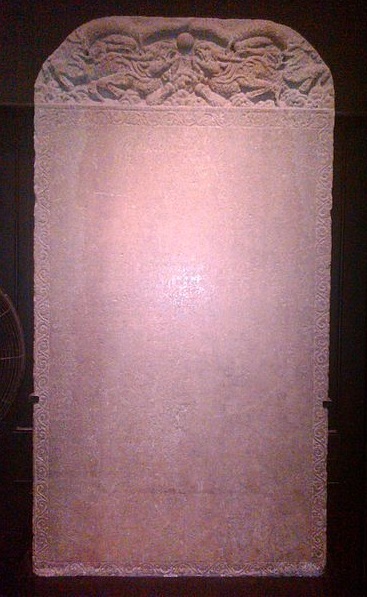

A bixi-born Yan Temple Renovation Stele dated Year 9 of Zhizheng era in Yuan Dynasty (AD 1349), in Qufu, Shandong, China

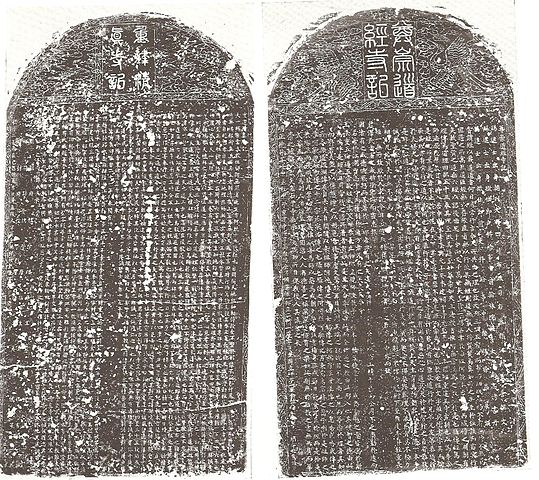

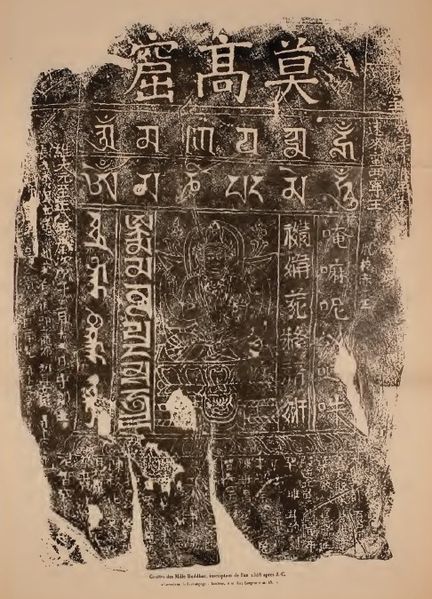

Chinese ink rubbings of the 1489 (left) and 1512 (right) steles left by the Kaifeng Jews Steles (Chinese: bei) have been the major medium of stone inscription in China since the Tang dynasty. Chinese steles are generally rectangular stone tablets upon which Chinese characters are carved intaglio with a funerary, commemorative, or edifying text. They can commemorate talented writers and officials, inscribe poems, portraits, or maps, and frequently contain the calligraphy of famous historical figures. In addition to their commemorative value, many Chinese steles are regarded as exemplars of traditional Chinese calligraphic scripts, especially the clerical script.

Chinese steles from before the Tang dynasty are rare: there are a handful from before the Qin dynasty, roughly a dozen from the Western Han, 160 from the Eastern Han, and several hundred from the Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern, and Sui dynasties. During the Han dynasty, tomb inscriptions (mùzhì) containing biographical information on deceased people began to be written on stone tablets rather than wooden ones.

Erecting steles at tombs or temples eventually became a widespread social and religious phenomenon. Emperors found it necessary to promulgate laws, regulating the use of funerary steles by the population. The Ming dynasty laws, instituted in the 14th century by its founder the Hongwu Emperor, listed a number of stele types available as status symbols to various ranks of the nobility and officialdom: the top noblemen and mandarins were eligible for steles installed on top of a stone tortoise and crowned with hornless dragons, while the lower-level officials had to be satisfied with steles with plain rounded tops, standing on simple rectangular pedestals.

Steles are found at nearly every significant mountain and historical site in China. The First Emperor made five tours of his domain in the 3rd century BC and had Li Si make seven stone inscriptions commemorating and praising his work, of which fragments of two survive. One of the most famous mountain steles is the 13 m (43 ft) high stele at Mount Tai with the personal calligraphy of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang commemorating his imperial sacrifices there in 725.

A number of such stone monuments have preserved the origin and history of China's minority religious communities. The 8th-century Christians of Xi'an left behind the Nestorian Stele, which survived adverse events of the later history by being buried underground for several centuries. Steles created by the Kaifeng Jews in 1489, 1512, and 1663, have survived the repeated flooding of the Yellow River that destroyed their synagogue several times, to tell us something about their world. China's Muslim have a number of steles of considerable antiquity as well, often containing both Chinese and Arabic text.

Thousands of steles, surplus to the original requirements, and no longer associated with the person they were erected for or to, have been assembled in Xi'an's Stele Forest Museum, which is a popular tourist attraction. Elsewhere, many unwanted steles can also be found in selected places in Beijing, such as Dong Yue Miao, the Five Pagoda Temple, and the Bell Tower, again assembled to attract tourists and also as a means of solving the problem faced by local authorities of what to do with them. The long, wordy, and detailed inscriptions on these steles are almost impossible to read for most are lightly engraved on white marble in characters only an inch or so in size, thus being difficult to see since the slabs are often 3m or more tall.

There are more than 100,000 surviving stone inscriptions in China. However, only approximately 30,000 have been transcribed or had rubbings made, and fewer than those 30,000 have been formally studied.

A relief sculpture showing a richly dressed human figure facing to the left with legs slightly spread. The arms are bent at the elbow with hands raised to chest height. Short vertical columns of hieroglyphs are positioned either side of the head, with another column at bottom left.

Intricately carved free standing stone shaft sculpted in the three-dimensional form of a richly dressed human figure, standing in an open grassy area.

Stela H, a high-relief in-the-round sculpture from Copán in Honduras

Maya stelae :

Stelae became closely associated with the concept of divine kingship and declined at the same time as this institution. The production of stelae by the Maya had its origin around 400 BC and continued through to the end of the Classic Period, around 900, although some monuments were reused in the Postclassic (c. 900–1521). The major city of Calakmul in Mexico raised the greatest number of stelae known from any Maya city, at least 166, although they are very poorly preserved.

Hundreds of stelae have been recorded in the Maya region, displaying a wide stylistic variation. Many are upright slabs of limestone sculpted on one or more faces, with available surfaces sculpted with figures carved in relief and with hieroglyphic text. Stelae in a few sites display a much more three-dimensional appearance where locally available stone permits, such as at Copán and Toniná. Plain stelae do not appear to have been painted nor overlaid with stucco decoration, but most Maya stelae were probably brightly painted in red, yellow, black, blue and other colours.

Ireland :

Ogham stone in Ratass Church, Ireland Ogham stones are vertical grave and boundary markers, erected at hundreds of sites in Ireland throughout the first millennium AD, bearing inscriptions in the Primitive Irish language. They have occasionally been described as "steles."

Horn of Africa :

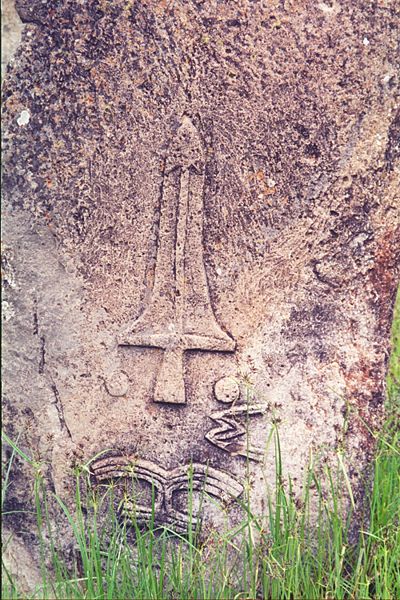

A sword symbol on a stele at Tiya The Horn of Africa contains many stelae. In the highlands of Ethiopia and Eritrea, the Axumites erected a number of large stelae, which served a religious purpose in pre-Christian times. One of these granite columns is the largest such structure in the world, standing at 90 feet.

Additionally, Tiya is one of nine megalithic pillar sites in the central Gurage Zone of Ethiopia. As of 1997, 118 stele were reported in the area. Along with the stelae in the Hadiya Zone, the structures are identified by local residents as Yegragn Dingay or "Gran's stone", in reference to Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmad "Gurey" or "Gran"), ruler of the Adal Sultanate.

The stelae at Tiya and other areas in central Ethiopia are similar to those on the route between Djibouti City and Loyada in Djibouti. In the latter area, there are a number of anthropomorphic and phallic stelae, which are associated with graves of rectangular shape flanked by vertical slabs. The Djibouti-Loyada stelae are of uncertain age, and some of them are adorned with a T-shaped symbol.

Near the ancient northwestern town of Amud in Somalia, whenever an old site had the prefix Aw in its name (such as the ruins of Awbare and Awbube), it denoted the final resting place of a local saint. Surveys by A.T. Curle in 1934 on several of these important ruined cities recovered various artefacts, such as pottery and coins, which point to a medieval period of activity at the tail end of the Adal Sultanate's reign. Among these settlements, Aw Barkhadle is surrounded by a number of ancient stelae. Burial sites near Burao likewise feature old stelae.

King Ezana's stele at Aksum

A victory stele of Naram-Sin, a 23rd-century BC Mesopotamian king Notable steles :

●

Stele of Vespasian

●

Merneptah Stele

● In the Western Hemisphere :

●

Mexico: Tres Zapotes Stela C, Izapa Stela 5, La Mojarra Stela 1

Gallery :

Princess Nefertiabet's funerary slab stele (c. 2575 BC) from Egypt's 4th dynasty

Egyptian grave stela of Nehemes-Ra-tawy, c. 760 – 656 BC

Stele #25 (c. 2500 BC) from the Petit Chasseur in Sion, Switzerland

A neolithic Sardinian menhir (c. 2500 BC) recovered at Laconi and assigned to the Abealzu-Filigosa culture

The lunette of the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1750 BC), depicting the king receiving his law from the sun god Shamash

Baal with Thunderbolt (c. 14th century BC), an Ugaritic stele from Syria

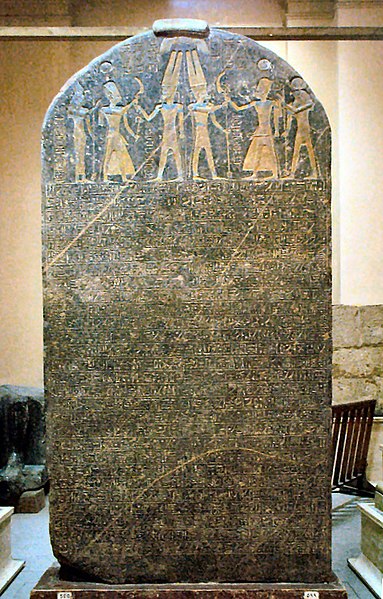

The Merneptah Stele (c. 1200 BC), engraved on the back of a reused stele of Amenhotep III's, with the earliest mention of the name Israel

An unusually well-preserved Greek herm (c. 520 BC), used as a boundary marker and to ward off evil

A votive stela honoring the Thracian goddess Bendis (c. 400 BC), carved at Athens

A herm of Demosthenes, a c. 1520 recreation of the c. 280 BC original located in the Athenian market

The Rosetta Stone (196 BC), establishing the divine cult of Ptolemy V

A Buddhist Stele from China, Northern Wei period, built sometime after 583

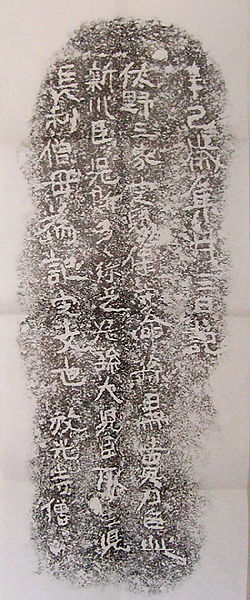

A rubbing of the Yamanoue Stele (681) in Takasaki, one of three protected steles in Japan

Stele 35 from Yaxchilan (8th century), depicting Lady Eveningstar, the consort of king Shield Jaguar II

The Nestorian Stele (781) records the success of the missionary Alopen in Tang China in Chinese and Syriac. It is borne by a Bixi and forbidden to travel abroad

Rodney's Stone, a slab cross from Early Medieval Scotland

Sueno's Stone (c. 9th century) in Forres, Scotland, displaying efforts at modern preservation of the Pictish stones

A rubbing of the Stele of Sulaiman, Prince of Xining (1348), bearing the Mani in six languages: Nepali, Tibetan, Uyghur, 'Phags-pa, Tangut, and Chinese

The Galle stele left by Zheng He on Sri Lanka in 1409 with trilingual inscriptions in Chinese, Tamil, and Persian

Tombstones (funerary stelae) at the Common Burying Ground and Island Cemetery, Newport, Rhode Island. Typical inscriptions include the names of the deceased interred under the stones. Ca. 18th century and later

A disc shaped gravestone or hilarri in Bidarray, western Pyrenees, Basque Country, featuring typical geometric and solar forms, as it was the custom since the period previous to Roman times

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |