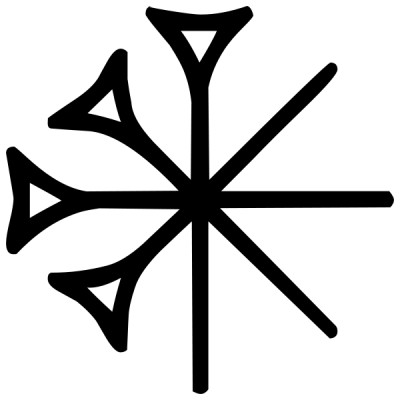

| AN

Ur III Sumerian cuneiform for An (and determinative sign for deities; cf. dingir) Anu

: Sky Father, King of the Gods, Lord of the Constellations

Anu, Anum, or Ilu (Akkadian: DAN), also called An (Sumerian: AN, “Sky”, “Heaven”), is the divine personification of the sky, supreme god, and ancestor of all the deities in ancient Mesopotamian religion. Anu was believed to be the supreme source of all authority, for the other gods and for all mortal rulers, and he is described in one text as the one "who contains the entire universe". He is identified with the north ecliptic pole centered in the constellation Draco and, along with his sons Enlil and Enki, constitutes the highest divine triad personifying the three bands of constellations of the vault of the sky. By the time of the earliest written records, Anu was rarely worshipped, and veneration was instead devoted to his son Enlil, but, throughout Mesopotamian history, the highest deity in the pantheon was always said to possess the anûtu, meaning "Heavenly power". Anu's primary role in myths is as the ancestor of the Anunnaki, the major deities of Sumerian religion. His primary cult center was the Eanna temple in the city of Uruk, but, by the Akkadian Period (c. 2334–2154 BCE), his authority in Uruk had largely been ceded to the goddess Inanna, the Queen of Heaven.

Anu's consort in the earliest Sumerian texts is the goddess Uraš, but she is later the goddess Ki and, in Akkadian texts, the goddess Antu, whose name is a feminine form of Anu. Anu briefly appears in the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, in which his daughter Ishtar (the East Semitic equivalent to Inanna) persuades him to give her the Bull of Heaven so that she may send it to attack Gilgamesh. The incident results in the death of Enkidu. In another legend, Anu summons the mortal hero Adapa before him for breaking the wing of the south wind. Anu orders for Adapa to be given the food and water of immortality, which Adapa refuses, having been warned beforehand by Enki that Anu will offer him the food and water of death. In ancient Hittite religion, Anu is a former ruler of the gods, who was overthrown by his son Kumarbi, who bit off his father's genitals and gave birth to the storm god Teshub. Teshub overthrew Kumarbi, avenged Anu's mutilation, and became the new king of the gods. This story was the later basis for the castration of Ouranos in Hesiod's Theogony.

Worship :

Part

of the front of a Babylonian temple to Ishtar in Uruk, built c.

1415 BCE, during the Kassite Period (c. 1600—1155 BCE). The

original Eanna temple in Uruk was first dedicated to Anu, but later

dedicated to Inanna.

Though Anu was the supreme god, he was rarely worshipped, and, by the time that written records began, the most important cult was devoted to his son Enlil. Anu's primary role in the Sumerian pantheon was as an ancestor figure; the most powerful and important deities in the Sumerian pantheon were believed to be the offspring of Anu and his consort Ki. These deities were known as the Anunnaki, which means "offspring of Anu". Although it is sometimes unclear which deities were considered members of the Anunnaki, the group probably included the "seven gods who decree": Anu, Enlil, Enki, Ninhursag, Nanna, Utu, and Inanna.

Anu's main cult center was the Eanna temple, whose name means "House of Heaven" (Sumerian: e2-anna; Cuneiform: E2.AN), in Uruk. Although the temple was originally dedicated to Anu, it was later transformed into the primary cult center of Inanna. After its dedication to Inanna, the temple seems to have housed priestesses of the goddess.

Anu was believed to be source of all legitimate power; he was the one who bestowed the right to rule upon gods and kings alike. According to scholar Stephen Bertman, Anu "... was the supreme source of authority among the gods, and among men, upon whom he conferred kingship. As heaven's grand patriarch, he dispensed justice and controlled the laws known as the meh that governed the universe." In inscriptions commemorating his conquest of Sumer, Sargon of Akkad, the founder of the Akkadian Empire, proclaims Anu and Inanna as the sources of his authority. A hymn from the early second millennium BCE professes that "his utterance ruleth over the obedient company of the gods".

Anu's original name in Sumerian is An, of which Anu is a Semiticized form. Anu was also identified with the Semitic god Ilu or El from early on. The functions of Anu and Enlil frequently overlapped, especially during later periods as the cult of Anu continued to wane and the cult of Enlil rose to greater prominence. In later times, Anu was fully superseded by Enlil. Eventually, Enlil was, in turn, superseded by Marduk, the national god of ancient Babylon. Nonetheless, references to Anu's power were preserved through archaic phrases used in reference to the ruler of the gods. The highest god in the pantheon was always said to possess the anûtu, which literally means "Heavenly power". In the Babylonian Enûma Eliš, the gods praise Marduk, shouting "Your word is Anu!"

Although Anu was a very important deity, his nature was often ambiguous and ill-defined; he almost never appears in Mesopotamian artwork and has no known anthropomorphic iconography. During the Kassite Period (c. 1600—1155 BCE) and Neo-Assyrian Period (911—609 BCE), Anu was represented by a horned cap. The Amorite god Amurru was sometimes equated with Anu. Later, during the Seleucid Empire (213—63 BCE), Anu was identified with Enmešara and Dumuzid.

Family

:

Anu is commonly described as the "father of the gods", and a vast array of deities were thought to have been his offspring over the course of Mesopotamian history. Inscriptions from Lagash dated to the late third millennium BC identify Anu as the father of Gatumdug, Baba, and Ninurta. Later literary texts proclaim Adad, Enki, Enlil, Girra, Nanna-Suen, Nergal and Šara as his sons and Inanna-Ishtar, Nanaya, Nidaba, Ninisinna, Ninkarrak, Ninmug, Ninnibru, Ninsumun, Nungal, and Nusku as his daughters. The demons Lamaštu, Asag, and the Sebettu were thought to have been Anu's creations. In Hittite mythology, Anu is the son of the god Alalu.

Mythology

:

In Sumerian, the designation "An" was used interchangeably with "the heavens" so that in some cases it is doubtful whether, under the term, the god An or the heavens is being denoted. In Sumerian cosmogony, heaven was envisioned as a series of three domes covering the flat earth; Each of these domes of heaven was believed to be made of a different precious stone. An was believed to be the highest and outermost of these domes, which was thought to be made of reddish stone. Outside of this dome was the primordial body of water known as Nammu. An's sukkal, or attendant, was the god Ilabrat.

Inanna myths :

The original Sumerian clay tablet of Inanna and Ebih, which is currently housed in the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago Inanna and Ebih, otherwise known as Goddess of the Fearsome Divine Powers, is a 184-line poem written in Sumerian by the Akkadian poetess Enheduanna. It describes An's granddaughter Inanna's confrontation with Mount Ebih, a mountain in the Zagros mountain range. An briefly appears in a scene from the poem in which Inanna petitions him to allow her to destroy Mount Ebih. An warns Inanna not to attack the mountain, but she ignores his warning and proceeds to attack and destroy Mount Ebih regardless.

The poem Inanna Takes Command of Heaven is an extremely fragmentary, but important, account of Inanna's conquest of the Eanna temple in Uruk. It begins with a conversation between Inanna and her brother Utu in which Inanna laments that the Eanna temple is not within their domain and resolves to claim it as her own. The text becomes increasingly fragmentary at this point in the narrative, but appears to describe her difficult passage through a marshland to reach the temple, while a fisherman instructs her on which route is best to take. Ultimately, Inanna reaches An, who is shocked by her arrogance, but nevertheless concedes that she has succeeded and that the temple is now her domain. The text ends with a hymn expounding Inanna's greatness. This myth may represent an eclipse in the authority of the priests of An in Uruk and a transfer of power to the priests of Inanna.

Akkadian :

Ancient

Mesopotamian terracotta relief showing Gilgamesh slaying the Bull

of Heaven, which Anu gives to his daughter Ishtar in Tablet IV of

the Epic of Gilgamesh after Gilgamesh spurns her amorous advances.

Adapa

myth :

Erra

and Išum :

Hittite

:

Later influence :

The

Mutilation of Uranus by Saturn (c. 1560) by Giorgio Vasari and Cristofano

Gherardi. The title uses the Latin names for Ouranos and Kronos,

respectively.

According to Walter Burkert, an expert on ancient Greek religion, direct parallels also exist between Anu and the Greek god Zeus. In particular, the scene from Tablet VI of the Epic of Gilgamesh in which Ishtar comes before Anu after being rejected by Gilgamesh and complains to her mother Antu, but is mildly rebuked by Anu, is directly paralleled by a scene from Book V of the Iliad. In this scene, Aphrodite, the later Greek development of Ishtar, is wounded by the Greek hero Diomedes while trying to save her son Aeneas. She flees to Mount Olympus, where she cries to her mother Dione, is mocked by her sister Athena, and is mildly rebuked by her father Zeus. Not only is the narrative parallel significant, but so is the fact that Dione's name is a feminization of Zeus's own, just as Antu is a feminine form of Anu. Dione does not appear throughout the rest of the Iliad, in which Zeus's consort is instead the goddess Hera. Burkert therefore concludes that Dione is clearly a calque of Antu.

The most direct equivalent to Anu in the Canaanite pantheon is Shamem, the personification of the sky, but Shamem almost never appears in myths and it is unclear whether the Canaanites ever regarded him as a previous ruler of the gods at all. Instead, the Canaanites seem to have ascribed Anu's attributes to El, the current ruler of the gods. In later times, the Canaanites equated El with Kronos rather than with Ouranos, and El's son Baal with Zeus. A narrative from Canaanite mythology describes the warrior-goddess Anat coming before El after being insulted, in a way that directly parallels Ishtar coming before Anu in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

El is characterized as the malk olam ("the eternal king") and, like Anu, he is "consistently depicted as old, just, compassionate, and patriarchal". In the same way that Anu was thought to wield the Tablet of Destinies, Canaanite texts mentions decrees issued by El that he alone may alter. In late antiquity, writers such as Philo of Byblos attempted to impose the dynastic succession framework of the Hittite and Hesiodic stories onto Canaanite mythology, but these efforts are forced and contradict what most Canaanites seem to have actually believed. Most Canaanites seem to have regarded El and Baal as ruling concurrently:

El is king, Baal becomes king. Both are kings over other gods, but El's kingship is timeless and unchanging. Baal must acquire his kingship, affirm it through the building of his temple, and defend it against adversaries; even so he loses it, and must be enthroned anew. El's kingship is static, Baal's is dynamic.

Anu as per Indian versions :

Angiras, Arthavan and Anu in Rig Ved

War of 10 Kings Ved and Avestan : Interpretation

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |