| SUSHRUT SAMHITA

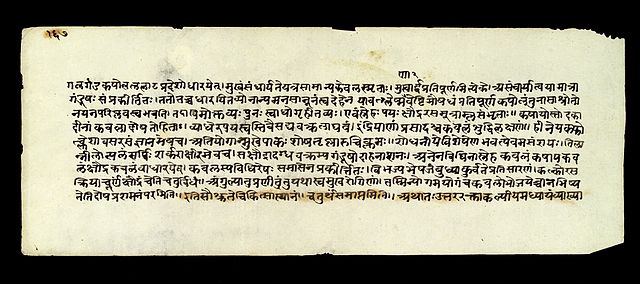

Palm leaves of the Sushruta Samhita or Sahottara-Tantra stored at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, from Nepal, the text is dated 12th-13th century while the art is dated 18th-19th century The Sushrut Samhita (IAST: Susrutsamhita, literally "Susrut's Compendium") is an ancient Sanskrit text on medicine and surgery, and one of the most important such treatises on this subject to survive from the ancient world. The Compendium of Susrut is one of the foundational texts of Ayurved (Indian traditional medicine), alongside the Charak-Samhita, the Bhela-Samhita, and the medical portions of the Bower Manuscript. It is one of the two foundational Hindu texts on medical profession that have survived from ancient India.

The Susrut Samhita is of great historical importance because it includes historically unique chapters describing surgical training, instruments and procedures which is still followed by modern science of surgery. One of the oldest Sushrut Samhita palm-leaf manuscripts is preserved at the Kaiser Library, Nepal. It is dated to 878 CE. [contradictory]

History

:

—

Sushrut Samhita Book 1, Chapter XXXIV

Rao in 1985 suggested that the original layer to the Sushrut Samhita was composed in 1st millennium BCE by "elder Sushrut" consisting of five books and 120 chapters, which was redacted and expanded with Uttara-tantra as the last layer of text in 1st millennium CE, bringing the text size to six books and 184 chapters. Walton et al., in 1994, traced the origins of the text to 1st millennium BCE.

Meulenbeld in his 1999 book states that the Susrut-samhita is likely a work that includes several historical layers, whose composition may have begun in the last centuries BCE and was completed in its presently surviving form by another author who redacted its first five sections and added the long, final section, the "Uttaratantra." It is likely that the Susrut-samhita was known to the scholar Drdhabala (fl. 300-500 CE, also spelled Dridhabala), which gives the latest date for the version of the work that has survived into the modern era.

Tipton in a 2008 historical perspectives review, states that uncertainty remains on dating the text, how many authors contributed to it and when. Estimates range from 1000 BCE, 800–600 BCE, 600 BCE, 600–200 BCE, 200 BCE, 1–100 CE, and 500 CE. Partial resolution of these uncertainties, states Tipton, has come from comparison of the Sushrut Samhita text with several Vedic hymns particularly the Atharvaveda such as the hymn on the creation of man in its 10th book, the chapters of Atreya Samhita which describe the human skeleton, better dating of ancient texts that mention Sushrut's name, and critical studies on the ancient Bower Manuscript by Hoernle. These information trace the first Sushrut Samhita to likely have been composed by about mid 1st millennium BCE.

Authorship :

A statue dedicated to Sushrut at the Patanjali Yogpeeth institute

in Haridwar. In the sign next to the statue, Patanjali Yogpeeth

attributes the title of Maharishi to Sushrut, claims a floruit of

1500 BC for him, and dubs him the "founding father of surgery",

and identifies the Sushrut Samhita as "the best and outstanding

commentary on Medical Science of Surgery".

Rao in 1985 suggested that the author of the original "layer" was "elder Sushrut" (Vrddha Sushrut). The text, states Rao, was redacted centuries later "by another Sushrut, then by Nagarjun, and thereafter Uttara-tantra was added as a supplement. It is generally accepted by scholars that there were several ancient authors called "Susrut" who contributed to this text.

Affiliation

:

The Sushrut Samhita and Carak Samhita have religious ideas throughout, states Steven Engler, who then concludes "Vedic elements are too central to be discounted as marginal". These ideas include treating the cow as sacred, extensive use of terms and same metaphors that are pervasive in the Hindu scriptures – the Veds, and the inclusion of theory of Karma, self (Atman) and Brahman (metaphysical reality) along the lines of those found in ancient Hindu texts. However, adds Engler, the text also includes another layer of ideas, where empirical rational ideas flourish in competition or cooperation with religious ideas.

The text may have Buddhist influences, since a redactor named Nagarjun has raised many historical questions, whether he was the same person of Mahayana Buddhism fame. Zysk states that the ancient Buddhist medical texts are significantly different from both Sushrut and Charak Samhita. For example, both Charak and Sushrut recommend Dhupana (fumigation) in some cases, the use of cauterization with fire and alkali in a class of treatments, and the letting out of blood as the first step in treatment of wounds. Nowhere in the Buddhist Pali texts, states Zysk, are these types of medical procedures mentioned. Similarly, medicinal resins (Laksha) lists vary between Sushrut and the Pali texts, with some sets not mentioned at all. While Sushrut and Charak are close, many afflictions and their treatments found in these texts are not found in Pali texts.

In general, states Zysk, Buddhist medical texts are closer to Sushrut than to Charak, and in his study suggests that the Sushrut Samhita probably underwent a "Hinduization process" around the end of 1st millennium BCE and the early centuries of the common era after the Hindu orthodox identity had formed. Clifford states that the influence was probably mutual, with Buddhist medical practice in its ancient tradition prohibited outside of the Buddhist monastic order by a precedent set by Buddha, and Buddhist text praise Buddha instead of Hindu gods in their prelude. The mutual influence between the medical traditions between the various Indian religions, the history of the layers of the Susrut-samhita remains unclear, a large and difficult research problem.

Susrut is reverentially held in Hindu tradition to be a descendant of Dhanvantari, the mythical god of medicine, or as one who received the knowledge from a discourse from Dhanvantari in Varanasi.

Manuscripts and transmission :

A page from the ancient medical text, Susrut samhita One of the oldest palm-leaf manuscripts of Sushrut Samhita has been discovered in Nepal. It is preserved at the Kaiser Library, Nepal as manuscript KL–699, with its digital copy archived by Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project (NGMCP C 80/7). The partially damaged manuscript consists of 152 folios, written on both sides, with 6 to 8 lines in transitional Gupta script. The manuscript has been verifiably dated to have been completed by the scribe on Sunday, April 13, 878 CE (Manadev Samvat 301).

Much of the scholarship on the Susrut-samhita is based on editions of the text that were published during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This includes the edition by Vaidya Yadavasarman Trivikramatmaja Acarya that also includes the commentary of the scholar Dalhan.

The printed editions are based on just a small subset of manuscripts that were available in the major publishing centres of Bombay, Calcutta and elsewhere when the editions were being prepared, sometimes as few as three or four manuscripts. But these do not adequately represent the large number of manuscript versions of the Susrut-samhita that have survived into the modern era. These manuscripts exist in the libraries in India and abroad today, perhaps a hundred or more versions of the text exist, and a critical edition of the Susrut-samhita is yet to be prepared.

Contents

:

—

Sushrut Samhita, Book 3, Chapter V

Scope

:

The Sushrut and Charaka texts differ in one major aspect, with Sushrut Samhita providing the foundation of surgery, while Charaka Samhita being primarily a foundation of medicine.

Chapters

:

The Susrut-Samhita is divided into two parts: the first five chapters, which are considered to be the oldest part of the text, and the "Later Section" (Skt. Uttaratantra) that was added by the author Nagarjuna. The content of these chapters is diverse, some topics are covered in multiple chapters in different books, and a summary according to the Bhishagratna's translation is as follows :

Sushrut

Samhita :

Human

skeleton :

The osteological system of Sushrut, states Hoernle, follows the principle of homology, where the body and organs are viewed as self-mirroring and corresponding across various axes of symmetry. The differences in the count of bones in the two schools is partly because Charaka Samhita includes thirty two teeth sockets in its count, and their difference of opinions on how and when to count a cartilage as bone (both count cartilages as bones, unlike current medical practice).

Surgery

:

—Sushrut

Samhita, Book 1, Chapter IX

The ancient text, state Menon and Haberman, describes haemorrhoidectomy, amputations, plastic, rhinoplastic, ophthalmic, lithotomic and obstetrical procedures.

The Sushrut mentions various methods including sliding graft, rotation graft and pedicle graft. Reconstruction of a nose (rhinoplasty) which has been cut off, using a flap of skin from the cheek is also described. Labioplasty too has received attention in the samahita.

Medicinal

herbs :

Reception

:

Transmission

outside India :

The text was known to the Khmer king Yasovarman I (fl. 889-900) of Cambodia. Susrut was also known as a medical authority in Tibetan literature.

In India, a major commentary on the text, known as Nibandha-samgraha, was written by Dalhan in ca. 1200 CE.

Modern

translations :

An English translation of both the Sushrut Samhita and Dalhana's commentary was published in three volumes by P. V. Sharma in 1999.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

_LACMA_M.87.271a-g_(1_of_8).jpg)