| ELAM

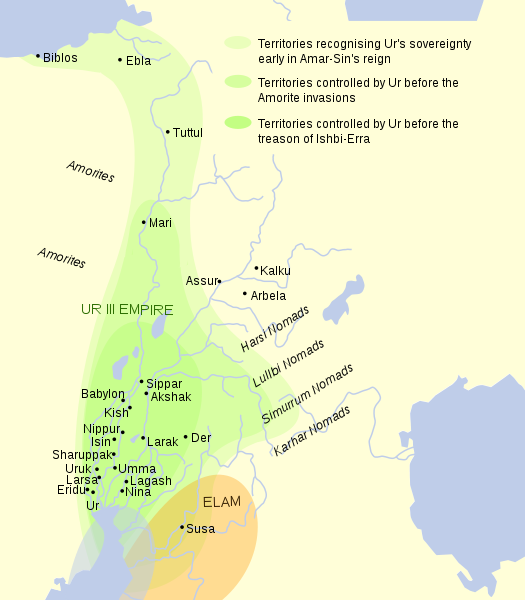

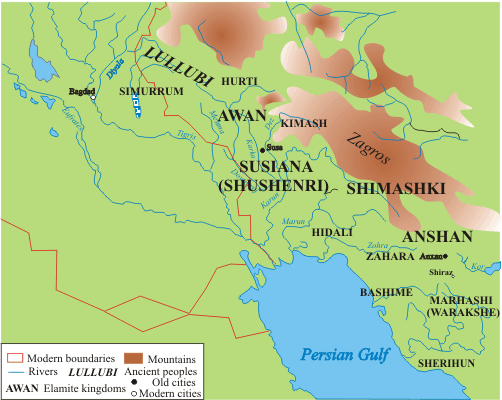

Map showing the area of the Elamite Empire (in orange) and the neighboring areas. The approximate Bronze Age extension of the Persian Gulf is shown Alternative

names : Elamites, Susiana

To view List of rulers of Elam click here.

Elam (Elamite: haltamti; Sumerian: NIM.MAki; Hebrew: Êlam; Old Persian: Uvja) was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretching from the lowlands of what is now Khuzestan and Ilam Province as well as a small part of southern Iraq. The modern name Elam stems from the Sumerian transliteration elam(a), along with the later Akkadian elamtu, and the Elamite haltamti. Elamite states were among the leading political forces of the Ancient Near East. In classical literature, Elam was also known as Susiana, a name derived from its capital Susa.

Elam was part of the early urbanization during the Chalcolithic period (Copper Age). The emergence of written records from around 3000 BC also parallels Sumerian history, where slightly earlier records have been found. In the Old Elamite period (Middle Bronze Age), Elam consisted of kingdoms on the Iranian plateau, centered in Anshan, and from the mid-2nd millennium BC, it was centered in Susa in the Khuzestan lowlands. Its culture played a crucial role during the Persian Achaemenid dynasty that succeeded Elam, when the Elamite language remained among those in official use. Elamite is generally considered a language isolate unrelated to any other languages. In accordance with geographical and archaeological matches, some historians argue that the Elamites comprise a large portion of the ancestors of the modern day Lurs whose language, Luri, split from Middle Persian.

Etymology

:

Exonyms included the Sumerian names NIM. MAki and ELAM, the Akkadian Elamû (masculine/neuter) and Elamitu (feminine) meant "resident of Susiana, Elamite".

In prehistory, Elam was centered primarily in modern Khuzestan and Ilam. The name Khuzestan is derived ultimately from the Old Persian Hujiya meaning Susa/Elam. In Middle Persian this became Huz "Susiana", and in modern Persian Xuz, compounded with the toponymic suffix -stån "place".

Geography :

Timeline of Elam In geographical terms, Susiana basically represents the Iranian province of Khuzestan around the river Karun. In ancient times, several names were used to describe this area. The great ancient geographer Ptolemy was the earliest to call the area Susiana, referring to the country around Susa.

Another ancient geographer, Strabo, viewed Elam and Susiana as two different geographic regions. He referred to Elam ("land of the Elymaei") as primarily the highland area of Khuzestan.

Disagreements over the location also exist in the Jewish historical sources says Daniel T. Potts. Some ancient sources draw a distinction between Elam as the highland area of Khuzestan, and Susiana as the lowland area. Yet in other ancient sources 'Elam' and 'Susiana' seem equivalent.

The uncertainty in this area extends also to modern scholarship. Since the discovery of ancient Anshan, and the realization of its great importance in Elamite history, the definitions were changed again. Some modern scholars argued that the centre of Elam lay at Anshan and in the highlands around it, and not at Susa in lowland Khuzistan.

Potts disagrees suggesting that the term 'Elam' was primarily constructed by the Mesopotamians to describe the area in general terms, without referring specifically either to the lowlanders or the highlanders, "Elam is not an Iranian term and has no relationship to the conception which the peoples of highland Iran had of themselves. They were Anshanites, Marhashians, Shimashkians, Zabshalians, Sherihumians, Awanites, etc. That Anshan played a leading role in the political affairs of the various highland groups inhabiting southwestern Iran is clear. But to argue that Anshan is coterminous with Elam is to misunderstand the artificiality and indeed the alienness of Elam as a construct imposed from without on the peoples of the southwestern highlands of the Zagros mountain range, the coast of Fars and the alluvial plain drained by the Karun-Karkheh river system.

History

:

•

Proto-Elamite : c. 3200 – c. 2700 BC (Proto-Elamite

script in Susa)

Kneeling Bull with Vessel. Kneeling bull holding a spouted vessel, Proto-Elamite period, (3100–2900 BC) Metropolitan Museum of Art, ref. 66.173 Proto-Elamite civilization grew up east of the Tigris and Euphrates alluvial plains; it was a combination of the lowlands and the immediate highland areas to the north and east. At least three proto-Elamite states merged to form Elam: Anshan (modern Fars Province), Awan (modern Lorestan Province) and Shimashki (modern Kerman). References to Awan are generally older than those to Anshan, and some scholars suggest that both states encompassed the same territory, in different eras (see Hanson, Encyclopædia Iranica). To this core Shushiana (modern Khuzestan) was periodically annexed and broken off. In addition, some Proto-Elamite sites are found well outside this area, spread out on the Iranian plateau; such as Warakshe, Sialk (now a suburb of the modern city of Kashan) and Jiroft in Kerman Province. The state of Elam was formed from these lesser states as a response to invasion from Sumer during the Old Elamite period. Elamite strength was based on an ability to hold these various areas together under a coordinated government that permitted the maximum interchange of the natural resources unique to each region. Traditionally, this was done through a federated governmental structure.

Proto-Elamite (Susa III) cylinder seal, 3150–2800 BC. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 6166 The Proto-Elamite city of Susa was founded around 4000 BC in the watershed of the river Karun. It is considered to be the site of Proto-Elamite cultural formation. During its early history, it fluctuated between submission to Mesopotamian and Elamite power. The earliest levels (22—17 in the excavations conducted by Le Brun, 1978) exhibit pottery that has no equivalent in Mesopotamia, but for the succeeding period, the excavated material allows identification with the culture of Sumer of the Uruk period. Proto-Elamite influence from the Mesopotamia in Susa becomes visible from about 3200 BC, and texts in the still undeciphered Proto-Elamite writing system continue to be present until about 2700 BC. The Proto-Elamite period ends with the establishment of the Awan dynasty.

Location of Kish The earliest known historical figure connected with Elam is the king Enmebaragesi of Kish (c. 2650 BC?), who subdued it, according to the Sumerian king list. Elamite history can only be traced from records dating to beginning of the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC) onwards.

The Proto-Elamite states in Jiroft and Zabol (not universally accepted), present a special case because of their great antiquity.

In

ancient Luristan, bronze-making tradition goes back to the mid-3rd

millennium BC, and has many Elamite connections. Bronze objects

from several cemeteries in the region date to the Early Dynastic

Period (Mesopotamia) I, and to Ur-III period c. 2900–2000

BC. These excavations include Kalleh Nisar, Bani Surmah, Chigha

Sabz, Kamtarlan, Sardant, and Gulal-i Galbi.

Polities during the Old Elamite period, and northern tribes of the Lullubi, Simurrum and Hurti

Silver cup with linear-Elamite inscription on it. Late 3rd millennium BC. National Museum of Iran The Old Elamite period began around 2700 BC. Historical records mention the conquest of Elam by Enmebaragesi, the Sumerian king of Kish in Mesopotamia. Three dynasties ruled during this period. Twelve kings of each of the first two dynasties, those of Awan (or Avan; c. 2400 – c. 2100 BC) and Simashki (c. 2100 – c. 1970 BC), are known from a list from Susa dating to the Old Babylonian period. Two Elamite dynasties said to have exercised brief control over parts of Sumer in very early times include Awan and Hamazi; and likewise, several of the stronger Sumerian rulers, such as Eannatum of Lagash and Lugal-anne-mundu of Adab, are recorded as temporarily dominating Elam.

Awan dynasty :

The Awan dynasty (2350–2150 BC) was partly contemporary with that of the Mesopotamian emperor Sargon of Akkad, who not only defeated the Awan king Luh-ishan and subjected Susa, but attempted to make the East Semitic Akkadian the official language there. From this time, Mesopotamian sources concerning Elam become more frequent, since the Mesopotamians had developed an interest in resources (such as wood, stone, and metal) from the Iranian plateau, and military expeditions to the area became more common. With the collapse of Akkad under Sargon's great great-grandson, Shar-kali-sharri, Elam declared independence under the last Awan king, Kutik-Inshushinak (c. 2240 – c. 2220 BC), and threw off the Akkadian language, promoting in its place the brief Linear Elamite script. Kutik-Inshushinnak conquered Susa and Anshan, and seems to have achieved some sort of political unity. Following his reign, the Awan dynasty collapsed as Elam was temporarily overrun by the Guti, another pre-Iranic people from what is now north west Iran who also spoke a language isolate.

Shimashki

dynasty :

Sukkalmah dynasty :

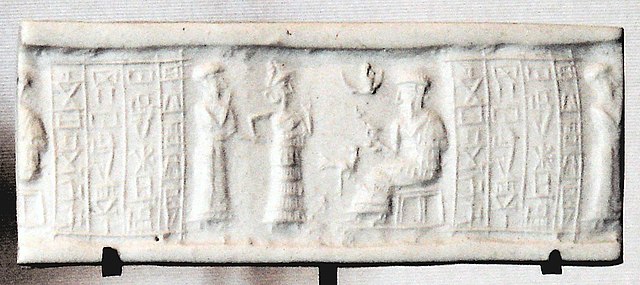

Seal

impression of King Ebarat, founder of the Sukkalmah Dynasty (also

called Epartid Dynasty after his name). Louvre Museum, reference

Sb 6225. King Ebarat appears enthroned. The inscription reads "Ebarat

the King. Kuk Kalla, son of Kuk-Sharum, servant of Shilhaha".

Notable Eparti dynasty rulers in Elam during this time include Sirukdukh (c. 1850 BC), who entered various military coalitions to contain the power of the south Mesopotamian states; Siwe-Palar-Khuppak, who for some time was the most powerful person in the area, respectfully addressed as "Father" by Mesopotamian kings such as Zimrilim of Mari, Shamshi-Adad I of Assyria, and even Hammurabi of Babylon; and Kudur-Nahhunte, who plundered the temples of southern Mesopotamia, the north being under the control of the Old Assyrian Empire. But Elamite influence in southern Mesopotamia did not last. Around 1760 BC, Hammurabi drove out the Elamites, overthrew Rim-Sin of Larsa, and established a short lived Babylonian Empire in Mesopotamia. Little is known about the latter part of this dynasty, since sources again become sparse with the Kassite rule of Babylon (from c. 1595 BC).

Trade

with the Indus Valley civilization :

Exchanges seem to have waned after 1900 BC, together with the disappearance of the Indus valley civilization.

Indian carnelian beads with white design, etched in white with an acid, imported to Susa in 2600–1700 BC. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 17751. These beads are identical with beads found in the Indus Civilization site of Dholavira.

Indus bracelet made of Fasciolaria Trapezium or Turbinella pyrum imported to Susa in 2600–1700 BC. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 14473. This type of bracelet was manufactured in Mohenjo-daro, Lothal and Balakot. It is engraved with a chevron design which is characteristic of all shell bangles of the Indus Valley, visible here.

Indus Valley Civilization weight in veined jasper, excavated in Susa in a 12th-century BC princely tomb. Louvre Museum Sb 17774 Middle

Elamite period (c. 1500 – c. 1100 BC) :

An ornate design on this limestone ritual vat from the Middle Elamite period depicts creatures with the heads of goats and the tails of fish (1500–1110 BC) The Middle Elamite period began with the rise of the Anshanite dynasties around 1500 BC. Their rule was characterized by an "Elamisation" of Susa, and the kings took the title "king of Anshan and Susa". While the first of these dynasties, the Kidinuids continued to use the Akkadian language frequently in their inscriptions, the succeeding Igihalkids and Shutrukids used Elamite with increasing regularity. Likewise, Elamite language and culture grew in importance in Susiana. The Kidinuids (c. 1500 – 1400 BC) are a group of five rulers of uncertain affiliation. They are identified by their use of the older title, "king of Susa and of Anshan", and by calling themselves "servant of Kirwashir", an Elamite deity, thereby introducing the pantheon of the highlands to Susiana. The city of Susa itself is one of the oldest in the world dating back to around 4200 BC. Since its founding Susa was known as a central power location for the Elamites and for later Persian dynasties. Susa's power would peak during the Middle Elamite period, when it would be the region's capital.

Kassite invasions :

Stele of Untash Napirisha, king of Anshan and Susa. Sandstone, ca. 1340–1300 BC Of the Igehalkids (c. 1400 – 1210 BC), ten rulers are known, though their number was possibly larger. Some of them married Kassite princesses. The Kassites were also a Language Isolate speaking people from the Zagros Mountains who had taken Babylonia shortly after its sacking by the Hittite Empire in 1595 BC. The Kassite king of Babylon Kurigalzu II who had been installed on the throne by Ashur-uballit I of the Middle Assyrian Empire (1366–1020 BC), temporarily occupied Elam around 1320 BC, and later (c. 1230 BC) another Kassite king, Kashtiliash IV, fought Elam unsuccessfully. Kassite-Babylonian power waned, as they became dominated by the northern Mesopotamian Middle Assyrian Empire. Kiddin-Khutran of Elam repulsed the Kassites by defeating Enlil-nadin-shumi in 1224 BC and Adad-shuma-iddina around 1222–1217 BC. Under the Igehalkids, Akkadian inscriptions were rare, and Elamite highland gods became firmly established in Susa.

Elamite Empire :

The Chogha Zanbil ziggurat site, built circa 1250 BC Under the Shutrukids (c. 1210 – 1100 BC), the Elamite empire reached the height of its power. Shutruk-Nakhkhunte and his three sons, Kutir-Nakhkhunte II, Shilhak-In-Shushinak, and Khutelutush-In-Shushinak were capable of frequent military campaigns into Kassite Babylonia (which was also being ravaged by the empire of Assyria during this period), and at the same time were exhibiting vigorous construction activity—building and restoring luxurious temples in Susa and across their Empire. Shutruk-Nakhkhunte raided Babylonia, carrying home to Susa trophies like the statues of Marduk and Manishtushu, the Manishtushu Obelisk, the Stele of Hammurabi and the stele of Naram-Sin. In 1158 BC, after much of Babylonia had been annexed by Ashur-Dan I of Assyria and Shutruk-Nakhkhunte, the Elamites defeated the Kassites permanently, killing the Kassite king of Babylon, Zababa-shuma-iddin, and replacing him with his eldest son, Kutir-Nakhkhunte, who held it no more than three years before being ejected by the native Akkadian speaking Babylonians. The Elamites then briefly came into conflict with Assyria, managing to take the Assyrian city of Arrapha (modern Kirkuk) before being ultimately defeated and having a treaty forced upon them by Ashur-Dan I.

Kutir-Nakhkhunte's son Khutelutush-In-Shushinak was probably of an incestuous relation of Kutir-Nakhkhunte's with his own daughter, Nakhkhunte-utu.[citation needed] He was defeated by Nebuchadnezzar I of Babylon, who sacked Susa and returned the statue of Marduk, but who was then himself defeated by the Assyrian king Ashur-resh-ishi I. He fled to Anshan, but later returned to Susa, and his brother Shilhana-Hamru-Lagamar may have succeeded him as last king of the Shutrukid dynasty. Following Khutelutush-In-Shushinak, the power of the Elamite empire began to wane seriously, for after the death of this ruler, Elam disappears into obscurity for more than three centuries.

Neo-Elamite

period (c. 1100 – 540 BC) :

Neo-Elamite II (c. 770 – 646 BC) :

Elamite archer fighting against the Neo-Assyrian troops of Ashurbanipal, and protecting wounded king Teumman, at the Battle of Ulai, 653 BC

Ashurbanipal's

campaign against Elam is triumphantly recorded in this relief showing

the sack of Hamanu in 647 BC. Here, flames rise from the city as

Assyrian soldiers topple it with pickaxes and crowbars and carry

off the spoils.

More details are known from the late 8th century BC, when the Elamites were allied with the Chaldean chieftain Merodach-baladan to defend the cause of Babylonian independence from Assyria. Khumbanigash (743–717 BC) supported Merodach-baladan against Sargon II, apparently without success; while his successor, Shutruk-Nakhkhunte II (716–699 BC), was routed by Sargon's troops during an expedition in 710, and another Elamite defeat by Sargon's troops is recorded for 708. The Assyrian dominion over Babylon was underlined by Sargon's son Sennacherib, who defeated the Elamites, Chaldeans and Babylonians and dethroned Merodach-baladan for a second time, installing his own son Ashur-nadin-shumi on the Babylonian throne in 700.

Shutruk-Nakhkhunte II, the last Elamite to claim the old title "king of Anshan and Susa", was murdered by his brother Khallushu, who managed to briefly capture the Assyrian governor of Babylonia Ashur-nadin-shumi and the city of Babylon in 694 BC. Sennacherib soon responded by invading and ravaging Elam. Khallushu was in turn assassinated by Kutir-Nakhkhunte, who succeeded him but soon abdicated in favor of Khumma-Menanu III (692–689 BC). Khumma-Menanu recruited a new army to help the Babylonians and Chaldeans against the Assyrians at the battle of Halule in 691. Both sides claimed the victory in their annals, but Babylon was destroyed by Sennacherib only two years later, and its Elamite allies defeated in the process.

The reigns of Khumma-Khaldash I (688–681 BC) and Khumma-Khaldash II (680–675 BC) saw a deterioration of Elamite-Babylonian relations, and both of them raided Sippar. At the beginning of Esarhaddon's reign in Assyria (681–669 BC), Nabu-zer-kitti-lišir, an ethnically Elamite governor in the south of Babylonia, revolted and besieged Ur, but was routed by the Assyrians and fled to Elam where the king of Elam, fearing Assyrian repercussions, took him prisoner and put him to the sword.

Urtaku (674–664 BC) for some time wisely maintained good relations with the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (668–627 BC), who sent wheat to Susiana during a famine. But these friendly relations were only temporary, and Urtaku was killed in battle during a failed Elamite attack on Assyria.

Relief of a woman being fanned by an attendant while she holds what may be a spinning device before a table with a bowl containing a whole fish (700–550 BC) His successor Tempti-Khumma-In-Shushinak (664–653 BC) attacked Assyria, but was defeated and killed by Ashurbanipal following the battle of the Ulaï in 653 BC; and Susa itself was sacked and occupied by the Assyrians. In this same year the Assyrian vassal Median state to the north fell to the invading Scythians and Cimmerians under Madius, and displacing another Assyrian vassal people, the Parsu (Persians) to Anshan which their king Teispes captured that same year, turning it for the first time into an Indo-Iranian kingdom under Assyrian dominance that would a century later become the nucleus of the Achaemenid dynasty. The Assyrians successfully subjugated and drove the Scythians and Cimmerians from their Iranian colonies, and the Persians, Medes and Parthians remained vassals of Assyria.

During a brief respite provided by the civil war between Ashurbanipal and his own brother Shamash-shum-ukin whom their father Esarhaddon had installed as the vassal king of Babylon, the Elamites both gave support to Shamash-shum-ukin, and indulged in fighting among themselves, so weakening the Elamite kingdom that in 646 BC Ashurbanipal devastated Susiana with ease, and sacked Susa. A succession of brief reigns continued in Elam from 651 to 640, each of them ended either due to usurpation, or because of capture of their king by the Assyrians. In this manner, the last Elamite king, Khumma-Khaldash III, was captured in 640 BC by Ashurbanipal, who annexed and destroyed the country.

In a tablet unearthed in 1854 by Henry Austin Layard, Ashurbanipal boasts of the destruction he had wrought :

Susa, the great holy city, abode of their Gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed … I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and I carried away their bones toward the land of Ashur. I devastated the provinces of Elam and on their lands I sowed salt.

Neo-Elamite III (646–539 BC) :

Elamite soldier in the Achaemenid army circa 470 BC, Xerxes I tomb relief The devastation was a little less complete than Ashurbanipal boasted, and a weak and fragmented Elamite rule was resurrected soon after with Shuttir-Nakhkhunte, son of Humban-umena III (not to be confused with Shuttir-Nakhkhunte, son of Indada, a petty king in the first half of the 6th century). Elamite royalty in the final century preceding the Achaemenids was fragmented among different small kingdoms, the united Elamite nation having been destroyed and colonised by the Assyrians. The three kings at the close of the 7th century (Shuttir-Nakhkhunte, Khallutush-In-Shushinak and Atta-Khumma-In-Shushinak) still called themselves "king of Anzan and of Susa" or "enlarger of the kingdom of Anzan and of Susa", at a time when the Achaemenid Persians were already ruling Anshan under Assyrian dominance.

The various Assyrian Empires, which had been the dominant force in the Near East, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, North Africa, Arabian peninsula and East Mediterranean for much of the period from the first half of the 14th century BC, began to unravel after the death of Ashurbanipal in 627 BC, descending into a series of bitter internal civil wars which also spread to Babylonia. The Iranian Medes, Parthians, Persians and Sagartians, who had been largely subject to Assyria since their arrival in the region around 1000 BC, quietly took full advantage of the anarchy in Assyria, and in 616 BC freed themselves from Assyrian rule.

The Medians took control of Elam during this period. Cyaxares the king of the Medes, Persians, Parthians and Sagartians entered into an alliance with a coalition of fellow former vassals of Assyria, including Nabopolassar of Babylon and Chaldea, and also the Scythians and Cimmerians, against Sin-shar-ishkun of Assyria, who was faced with unremitting civil war in Assyria itself. This alliance then attacked a disunited and war weakened Assyria, and between 616 BC and 599 BC at the very latest, had conquered its vast empire which stretched from the Caucasus Mountains to Egypt, Libya and the Arabian Peninsula, and from Cyprus and Ephesus to Persia and the Caspian Sea.

The major cities in Assyria itself were gradually taken; Arrapha (modern Kirkuk) and Kalhu (modern Nimrud) in 616 BC, Ashur, Dur-Sharrukin and Arbela (modern Erbil) in 613, Nineveh falling in 612, Harran in 608 BC, Carchemish in 605 BC, and finally Dur-Katlimmu by 599 BC. Elam, already largely destroyed and subjugated by Assyria, thus became easy prey for the Median dominated Iranian peoples, and was incorporated into the Median Empire (612–546 BC) and then the succeeding Achaemenid Empire (546–332 BC), with Assyria suffering the same fate.

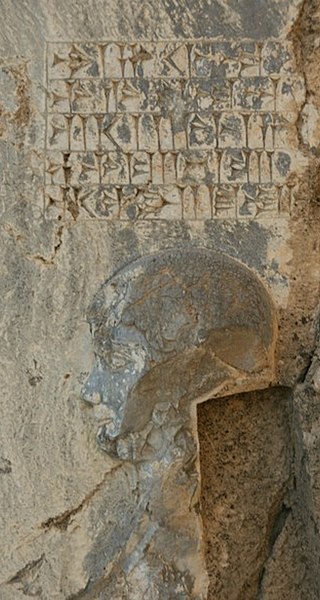

ššina, one of the last kings of Elam circa 522 BC was toppled, enchained and killed by Darius the Great. The label over him says: "This is ššina. He lied, saying "I am king of Elam."" The prophet Ezekiel describes the status of their power in the 12th year of the Hebrew Babylonian Captivity in 587 BCE :

There is Elam and all her multitude, All around her grave, All of them slain, fallen by the sword, Who have gone down uncircumcised to the lower parts of the earth, Who caused their terror in the land of the living; Now they bear their shame with those who go down to the Pit. (Ezekiel 32:24)

Their successors Khumma-Menanu and Shilhak-In-Shushinak II bore the simple title "king", and the final king Tempti-Khumma-In-Shushinak used no honorific at all. In 540 BC, Achaemenid rule began in Susa.

Elymais

(187 BC - 224 AD) :

Art :

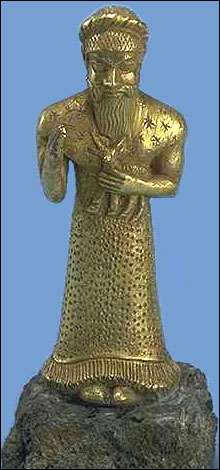

Golden statuette of a man (probably a king) carrying a goat. Susa, Iran, c. 1500–1200 BC (Middle Elamite period)

Statuettes :

While archaeologists cannot be certain that the location where these figures were found indicates a date before or in the time of the Elamite king Shilhak-Inshushinak, stylistic features can help ground the figures in a specific time period. The hairstyle and costume of the figures which are strewn with dots and hemmed with short fringe at the bottom, and the precious metals point to a date in the latter part of the second millennium BC rather than to the first millennium.

In general, any gold or silver statuettes which represent the king making a sacrifice not only served a religious function, but also revealed the significance of displaying wealth that should not be overlooked.

Seals :

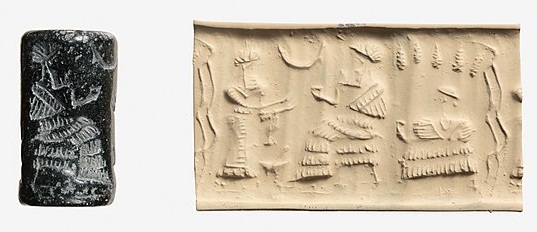

Cylinder seal and modern impression- worshiper before a seated ruler or deity; seated female under a grape arbor MET DP370181 Elamite seals reached their peak of complexity in the 4th millennium BC when their shape became cylindrical rather than stamp-like. Seals were primarily used as a form of identification and were often made out of precious stones. Because seals for different time periods had different designs and themes, seals and seal impressions can be used to track the various phases of the Elamite Empire and can teach a lot about the empire in ways which other forms of documentation cannot.

The seal pictured shows two seated figures holding cups with a man in front of them wearing a long robe next to a table. A man is sitting on a throne, presumably the king, and is in a wrapped robe. The second figure, perhaps his queen, is draped in a wide, flounced garment and is elevated on a platform beneath an overhanging vine. A crescent is shown in the field.

Statue of Queen Napir-Asu :

Statue of Napirasu This life-size votive offering of Queen Napir-Asu was commissioned around 1300 BC in Susa, Iran. It is made of copper using the lost-wax casting method and rests on a solid bronze frame that weighs 1750 kg (3760 lb). This statue is different from many other Elamite statues of women because it resembles male statues due to the wide belt on the dress and the patterns which closely resemble those on male statues.

The inscription on the side of the statue curses anyone, specifically men, who attempts to destroy the statue: "I, Napir-Asu, wife of Untash-Napirisha. He who would seize my statue, who would smash it, who would destroy its inscription, who would erase my name, may he be smitten by the curse of Napirisha, of Kiririsha, and of Inshushinka, that his name shall become extinct, that his offspring be barren, that the forces of Beltiya, the great goddess, shall sweep down on him. This is Napir-Asu's offering."

Stele

of Untash Napirisha :

King Untash Napirisha dedicated the stele to the god Ishushinak. Like other forms of art in the ancient Near East, this one portrays a king ceremonially recognizing a deity. This stele is unique in that the acknowledgement between king and god is reciprocal.

Religion :

A

carved chlorite vase decorated with a relief depicting a "two-horned"

figure wrestling with serpent goddesses. The Elamite artifact was

discovered by Iran's border police in the possession of historical

heritage traffickers, en route to Turkey, and was confiscated. Style

is determined to be from "Jiroft".[citation needed]

In the later period, Elam worshipped a supreme triad consisting of Inshushinak (originally the civic protector god of Susa, eventually the leader of the triad :401 and guarantor of the monarchy), Kiririsha (an earth/mother goddess in southern Elam :406), and Khumban (a sky god). Other deities include Pinikir (a mother goddess, and possibly originally chief deity, in northern Elam, :400 later supplanted by or identified with Kiririsha) and Jabru (a god of the underworld). There were also imported deities, such as Beltiya.

Language

:

The Elamite language may have survived as late as the early Islamic period (roughly contemporary with the early medieval period in Europe). Among other Islamic medieval historians, Ibn al-Nadim, for instance, wrote that "The Iranian languages are Fahlavi (Pahlavi), Dari (not to be confused with Dari Persian in modern Afghanistan), Khuzi, Persian and Suryani (Assyrian)", and Ibn Moqaffa noted that Khuzi was the unofficial language of the royalty of Persia, "Khuz" being the corrupted name for Elam.

Suggested

relations to other language families :

Legacy :

The Assyrians had utterly destroyed the Elamite nation, but new polities emerged in the area after Assyrian power faded. Among the nations that benefited from the decline of the Assyrians were the Iranian tribes, whose presence around Lake Urmia to the north of Elam is attested from the 9th century BC in Assyrian texts. Some time after that region fell to Madius the Scythian (653 BC), Teispes, son of Achaemenes, conquered Elamite Anshan in the mid 7th century BC, forming a nucleus that would expand into the Persian Empire. They were largely regarded as vassals of the Assyrians, and the Medes, Mannaeans, and Persians paid tribute to Assyria from the 10th century BC until the death of Ashurbanipal in 627 BC. After his death, the Medes played a major role in the destruction of the weakened Assyrian Empire in 612 BC.

The rise of the Achaemenids in the 6th century BC brought an end to the existence of Elam as an independent political power "but not as a cultural entity" (Encyclopædia Iranica, Columbia University). Indigenous Elamite traditions, such as the use of the title "king of Anshan" by Cyrus the Great; the "Elamite robe" worn by Cambyses I of Anshan and seen on the famous winged genii at Pasargadae; some glyptic styles; the use of Elamite as the first of three official languages of the empire used in thousands of administrative texts found at Darius’ city of Persepolis; the continued worship of Elamite deities; and the persistence of Elamite religious personnel and cults supported by the crown, formed an essential part of the newly emerging Achaemenid culture in Persian Iran. The Elamites thus became the conduit by which achievements of the Mesopotamian civilizations were introduced to the tribes of the Iranian plateau.

Conversely, remnants of Elamite had "absorbed Iranian influences in both structure and vocabulary" by 500 BC, suggesting a form of cultural continuity or fusion connecting the Elamite and the Persian periods.

The name of "Elam" survived into the Hellenistic period and beyond. In its Greek form, Elymais, it emerges as designating a semi-independent state under Parthian suzerainty during the 2nd century BC to the early 3rd century AD. In Acts 2:8–9 in the New Testament, the language of the Elamites is one of the languages heard at the Pentecost. From 410 onwards Elam (Beth Huzaye) was the senior metropolitan province of the Church of the East, surviving into the 14th century. Indian Carmelite historian John Marshal has proposed that the root of Carmelite history in the Indian subcontinent could be traced to the promise of restoration of Elam (Jeremiah 49:39). [unreliable source]

A 4.5 inch long lapis lazuli dove is studded with gold pegs. Dated 1200 BC from Susa, a city later on shared with the Achaemenids

Elamite reliefs at Eshkaft-e Salman. The picture of a woman with dignity shows the importance of women in the Elamite era In modern Iran, Ilam Province and Khuzestan Province are named after Elam civilization. Khuzestan means land of the Khuzis and Khuzi itself is a Middle Persian name for Elamites.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |