| SUSA

Susa, Iran

The Palace of Darius I in Susa Location

: Shush, Khuzestan Province, Iran

Susa (Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform: šušinki; Persian: Šuš; Hebrew: Šušan; Old Persian: Çuša) was an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains about 250 km (160 mi) east of the Tigris River, between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers. One of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East, Susa served as the capital of Elam and the Achaemenid Empire, and remained a strategic centre during the Parthian and Sasanian periods.

The site currently consists of three archaeological mounds, covering an area of around one square kilometre. The modern Iranian town of Shush is located on the site of ancient Susa. Shush is identified as Shushan, mentioned in the Book of Esther and other Biblical books.

Name

:

Literary references :

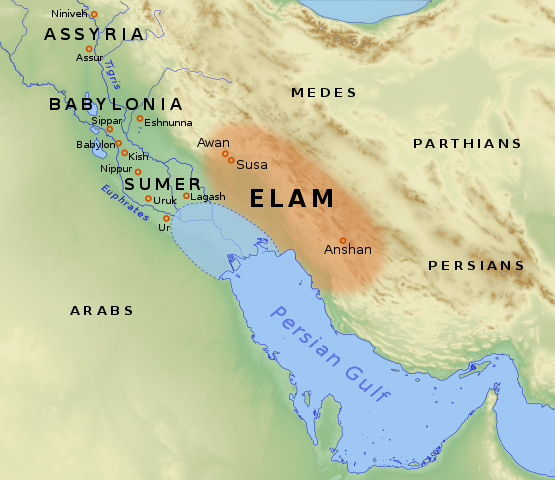

Map showing the area of the Elamite kingdom (in orange) and the neighboring areas. The approximate Bronze Age extension of the Persian Gulf is shown Susa was one of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East. In historic literature, Susa appears in the very earliest Sumerian records: for example, it is described as one of the places obedient to Inanna, patron deity of Uruk, in Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratt.

Biblical

texts :

Other

Religious texts :

Excavation history :

Site of Susa

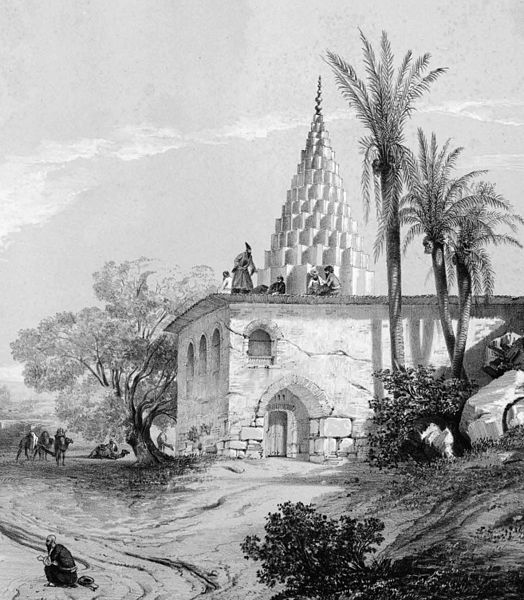

Assyria. Ruins of Susa, Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection The site was examined in 1836 by Henry Rawlinson and then by A. H. Layard.

In 1851, some modest excavation was done by William Loftus, who identified it as Susa.

In 1885 and 1886 Marcel-Auguste Dieulafoy and Jane Dieulafoy began the first French excavations. Almost all of the excavations at Susa, post 1885, were organized and authorized by the French Monarchy.

Jacques de Morgan conducted major excavations from 1897 until 1911. The excavations that were conducted in Susa brought many artistic and historical artifacts back to France. These artifacts filled multiple halls in the Museum of the Louvre throughout the late 1890s and early 1900s. These efforts continued under Roland De Mecquenem until 1914, at the beginning of World War I. French work at Susa resumed after the war, led by De Mecquenem, continuing until World War II in 1940. To supplement the original publications of De Mecquenem the archives of his excavation have now been put online thanks to a grant from the Shelby White Levy Program.

Roman Ghirshman took over direction of the French efforts in 1946, after the end of the war. Together with his wife Tania Ghirshman, he continued there until 1967. The Ghirshmans concentrated on excavating a single part of the site, the hectare sized Ville Royale, taking it all the way down to bare earth. The pottery found at the various levels enabled a stratigraphy to be developed for Susa. During the 1970s, excavations resumed under Jean Perrot.

History

:

The founding of Susa corresponded with the abandonment of nearby villages. Potts suggests that the settlement may have been founded to try to reestablish the previously destroyed settlement at Chogha Mish. Previously, Chogha Mish was also a very large settlement, and it featured a similar massive platform that was later built at Susa.

Another important settlement in the area is Chogha Bonut, that was discovered in 1976.

Susa I period (4200 - 3800 BCE) :

Goblet and cup, Iran, Susa I style, 4th millennium BC – Ubaid period; goblet height c. 12 cm; Sèvres – Cité de la céramique, France Shortly after Susa was first settled over 6000 years ago, its inhabitants erected a monumental platform that rose over the flat surrounding landscape. The exceptional nature of the site is still recognizable today in the artistry of the ceramic vessels that were placed as offerings in a thousand or more graves near the base of the temple platform.

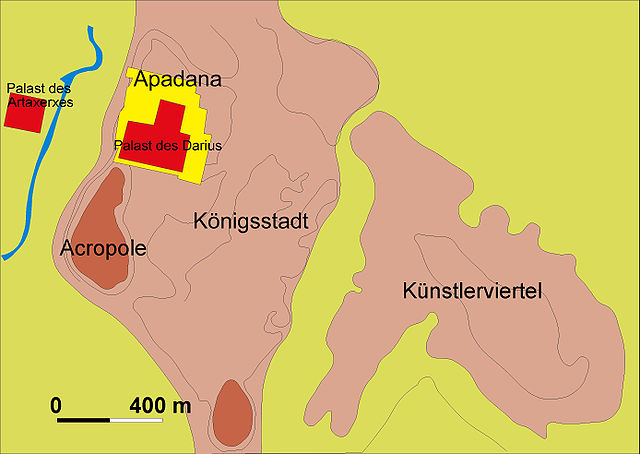

Susa's earliest settlement is known as Susa I period (c. 4200–3900 BCE). Two settlements named by archaeologists Acropolis (7 ha) and Apadana (6.3 ha), would later merge to form Susa proper (18 ha). The Apadana was enclosed by 6m thick walls of rammed earth (this particular place is named Apadana because it also contains a late Achaemenid structure of this type).

Nearly two thousand pots of Susa I style were recovered from the cemetery, most of them now in the Louvre. The vessels found are eloquent testimony to the artistic and technical achievements of their makers, and they hold clues about the organization of the society that commissioned them. Painted ceramic vessels from Susa in the earliest first style are a late, regional version of the Mesopotamian Ubaid ceramic tradition that spread across the Near East during the fifth millennium BC. Susa I style was very much a product of the past and of influences from contemporary ceramic industries in the mountains of western Iran. The recurrence in close association of vessels of three types—a drinking goblet or beaker, a serving dish, and a small jar—implies the consumption of three types of food, apparently thought to be as necessary for life in the afterworld as it is in this one. Ceramics of these shapes, which were painted, constitute a large proportion of the vessels from the cemetery.

Others are coarse cooking-type jars and bowls with simple bands painted on them and were probably the grave goods of the sites of humbler citizens as well as adolescents and, perhaps, children. The pottery is carefully made by hand. Although a slow wheel may have been employed, the asymmetry of the vessels and the irregularity of the drawing of encircling lines and bands indicate that most of the work was done freehand.

Copper metallurgy is also attested during this period, which was contemporary with metalwork at some highland Iranian sites such as Tepe Sialk.

Louvre Suse I Boisseau décor géométrique

Louvre Suse I Nécropole du tell de l'Acropole Coupe décor géométrique

Master of animals, Susa I, Louvre Sb 2246

Sun and deities, Susa I, Louvre Susa II and Uruk influence (3800 - 3100 BCE) :

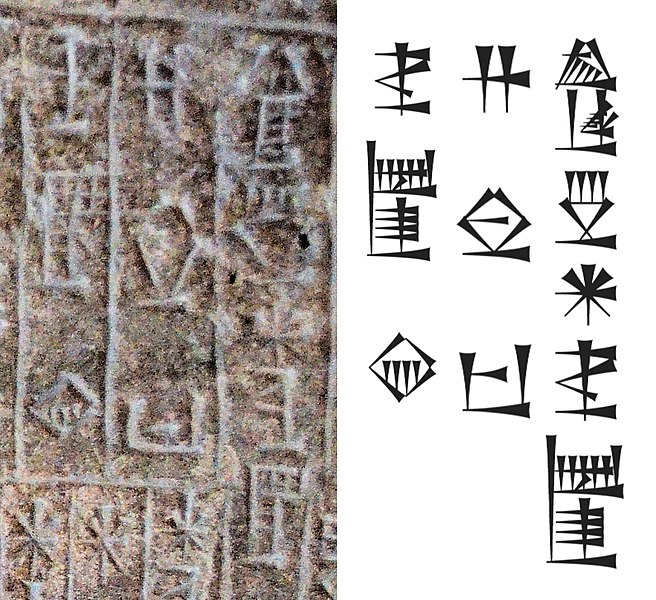

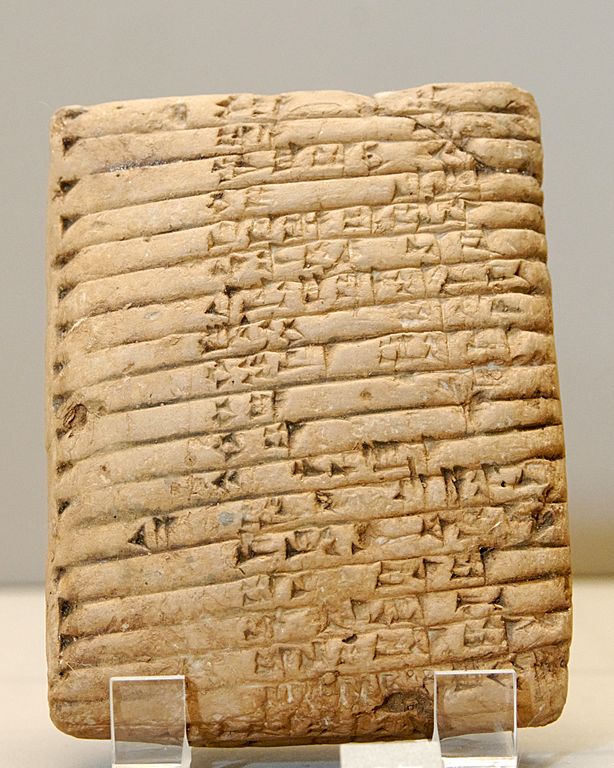

Globular envelope with the accounting tokens. Clay, Uruk period (c. 3500 BCE). From the Tell of the Acropolis in Susa. The Louvre Susa came within the Uruk cultural sphere during the Uruk period. An imitation of the entire state apparatus of Uruk, proto-writing, cylinder seals with Sumerian motifs, and monumental architecture is found at Susa. According to some scholars, Susa may have been a colony of Uruk.

There is some dispute about the comparative periodization of Susa and Uruk at this time, as well as about the extent of Uruk influence in Susa. Recent research indicates that Early Uruk period corresponds to Susa II period.

Click here to view uruk in Sumerian mythology.

Click here to view uruk in mahabharat.

King-priest with bow fighting enemies, with horned temple in the center. Susa II or Uruk period (3800-3100 BCE), found in excavations at Susa. Louvre Museum D. T. Potts, argue that the influence from the highland Iranian Khuzestan area in Susa was more significant at the early period, and also continued later on. Thus, Susa combined the influence of two cultures, from the highland area and from the alluvial plains. Also, Potts stresses the fact that the writing and numerical systems of Uruk were not simply borrowed in Susa wholesale. Rather, only partial and selective borrowing took place, that was adapted to Susa's needs. Despite the fact that Uruk was far larger than Susa at the time, Susa was not its colony, but still maintained some independence for a long time, according to Potts. An architectural link has also been suggested between Susa, Tal-i Malyan, and Godin Tepe at this time, in support of the idea of the parallel development of the protocuneiform and protoelamite scripts.

Some scholars believe that Susa was part of the greater Uruk culture. Holly Pittman, an art historian at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia says, "they [Susanians] are participating entirely in an Uruk way of life. They are not culturally distinct; the material culture of Susa is a regional variation of that on the Mesopotamian plain". Gilbert Stein, director of the University of Chicago's Oriental Institute, says that "An expansion once thought to have lasted less than 200 years now apparently went on for 700 years. It is hard to think of any colonial system lasting that long. The spread of Uruk material is not evidence of Uruk domination; it could be local choice".

Work in the granaries, Susa II, Louvre

Priest-King with bow and arrows, Susa II, Louvre

Prisoners, Susa II, Louvre

Orant statuette, Susa II, Louvre Susa

III, or "Proto-Elamite", period (3100–2700 BCE)

:

Ambiguous reference to Elam (Cuneiform; NIM) appear also in this period in Sumerian records. Susa enters history during the Early Dynastic period of Sumer. A battle between Kish and Susa is recorded in 2700 BCE, when En-me-barage-si is said to have "made the land of Elam submit".

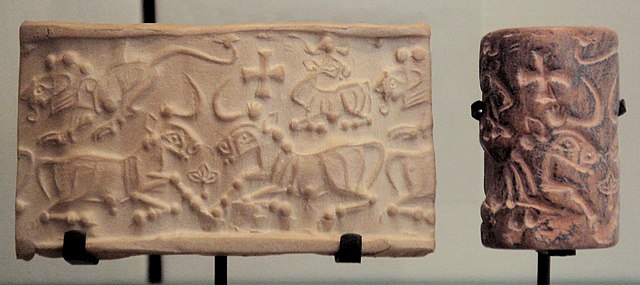

Susa III/ Proto-Elamite cylinder seal, 3150–2800 BC. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 1484

Susa III/ Proto-Elamite cylinder seal 3150–2800 BC Mythological being on a boat Louvre Museum Sb 6379

Susa III/ Proto-Elamite cylinder seal 3150–2800 BC Louvre Museum Sb 6166

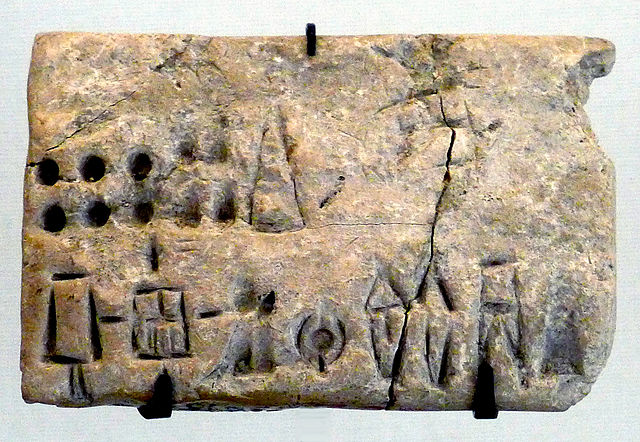

Economical tablet in Proto-Elamite script, Suse III, Louvre Museum, reference Sb 15200, circa 3100-2850 BCE Elamites :

Puzur-Inshushinak Ensi Shushaki, "Puzur-Inshushinak Ensi (Governor) of Susa", in the "Table au Lion", dated 2100 BCE, Louvre Museum In the Sumerian period, Susa was the capital of a state called Susiana (Šušan), which occupied approximately the same territory of modern Khuzestan Province centered on the Karun River. Control of Susiana shifted between Elam, Sumer, and Akkad. Susiana is sometimes mistaken as synonymous with Elam but, according to F. Vallat, it was a distinct cultural and political entity.

During the Elamite monarchy, many riches and materials were brought to Susa from the plundering of other cities. This was mainly due to the fact of Susa's location on Iran's South Eastern region, closer to the city of Babylon and cities in Mesopotamia.

The use of the Elamite language as an administrative language was first attested in texts of ancient Ansan, Tall-e Mal-yan, dated 1000 BCE. Previous to the era of Elamites, the Akkadian language was responsible for most or all of the text used in ancient documents. Susiana was incorporated by Sargon the Great into his Akkadian Empire in approximately 2330 BCE.

Silver cup from Marvdasht, Iran, with a linear-Elamite inscription from the time of Kutik-Inshushinak. National Museum of Iran The main goddess of the city was Nanaya, who had a significant temple in Susa.

Old Elamite period (c. 2700 – 1500 BCE) :

Dynastic list of twelve kings of Awan dynasty and twelve kings of the Shimashki Dynasty, 1800–1600 BCE, Susa, Louvre Museum Sb 17729 The Old Elamite period began around 2700 BCE. Historical records mention the conquest of Elam by Enmebaragesi, the Sumerian king of Kish in Mesopotamia. Three dynasties ruled during this period. Twelve kings of each of the first two dynasties, those of Awan (or Avan; c. 2400–2100 BCE) and Simashki (c. 2100–1970 BC), are known from a list from Susa dating to the Old Babylonian period. Two Elamite dynasties said to have exercised brief control over parts of Sumer in very early times include Awan and Hamazi; and likewise, several of the stronger Sumerian rulers, such as Eannatum of Lagash and Lugal-anne-mundu of Adab, are recorded as temporarily dominating Elam.

Kutik-Inshushinak

:

The city was subsequently conquered by the neo-Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur and held until Ur finally collapsed at the hands of the Elamites under Kindattu in ca. 2004 BCE. At this time, Susa became an Elamite capital under the Epartid dynasty.

Indus-Susa

relations (2600 - 1700 BCE) :

Impression of an Indus cylinder seal discovered in Susa, in strata dated to 2600-1700 BCE. Elongated buffalo with line of standard Indus script signs. Tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 2425. Indus script numbering convention per Asko Parpola.

Indus round seal with impression. Elongated buffalo with Harappan script imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 5614

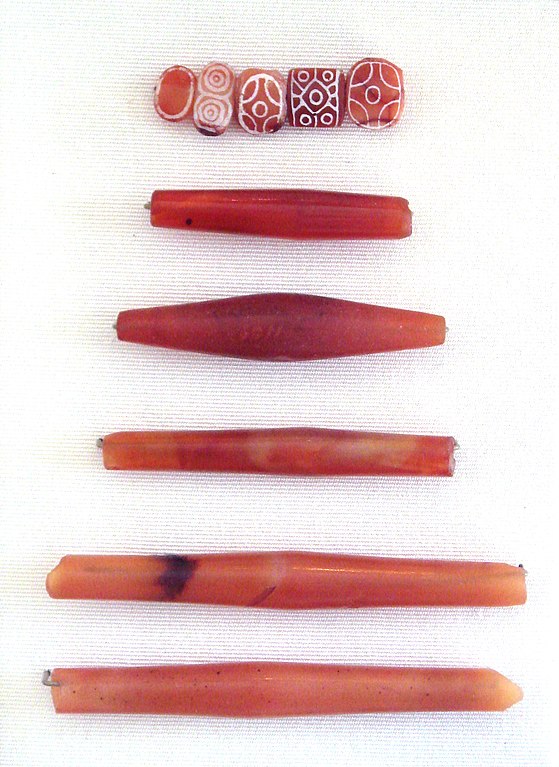

Indian carnelian beads with white design, etched in white with an alkali through a heat process, imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 17751. These beads are identical with beads found in the Indus Civilization site of Dholavira.

Indus bracelet, front and back, made of Pleuroploca trapezium or Turbinella pyrum imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 14473. This type of bracelet was manufactured in Mohenjo-daro, Lothal and Balakot. The back is engraved with an oblong chevron design which is typical of shell bangles of the Indus Civilization.

Indus Valley Civilization carnelian beads excavated in Susa

Jewelry with components from the Indus, Central Asia and Northern-eastern Iran found in Susa dated to 2600-1700 BCE Middle Elamite period (c. 1500 – 1100 BCE) :

Middle-Elamite basrelief of warrior gods, Susa, 1600-1100 BCE Around 1500 BCE, the Middle Elamite period began with the rise of the Anshanite dynasties. Their rule was characterized by an "Elamisation" of Susa, and the kings took the title "king of Anshan and Susa". While, previously, the Akkadian language was frequently used in inscriptions, the succeeding kings, such as the Igihalkid dynasty of c. 1400 BCE, tried to use Elamite. Thus, Elamite language and culture grew in importance in Susiana.

This was also the period when the Elamite pantheon was being imposed in Susiana. This policy reached its height with the construction of the political and religious complex at Chogha Zanbil, 30 km (19 mi) south-east of Susa.

In ca. 1175 BCE, the Elamites under Shutruk-Nahhunte plundered the original stele bearing the Code of Hammurabi and took it to Susa. Archeologists found it in 1901. Nebuchadnezzar I of the Babylonian empire plundered Susa around fifty years later.

An ornate design on this limestone ritual vat from the Middle Elamite period depicts creatures with the heads of goats and the tails of fish, Susa, 1500–1110 BCE

The Ziggurat at Chogha Zanbil was built by Elamite king Untash-Napirisha circa 1300 BCE

Susa, Middle-Elamite model of a sun ritual, circa 1150 BCE Neo-Elamite

period (c. 1100 – 540 BCE) :

"Susa, the great holy city, abode of their gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed. . . .I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and I carried away their bones toward the land of Ashur. I devastated the provinces of Elam and, on their lands, I sowed salt."

Assyrian rule of Susa began in 647 BCE and lasted till Median capture of Susa in 617 BCE.

Susa after Achaemenid Persian Conquest :

Statue of Darius the Great, National Museum of Iran

Archers frieze from Darius' palace at Susa. Detail of the beginning of the frieze

The 24 countries subject to the Achaemenid Empire at the time of Darius, on the Statue of Darius I Susa underwent a major political and ethnocultural transition when it became part of the Persian Achaemenid empire between 540 and 539 BCE when it was captured by Cyrus the Great during his conquest of Elam (Susiana), of which Susa was the capital. The Nabonidus Chronicle records that, prior to the battle(s), Nabonidus had ordered cult statues from outlying Babylonian cities to be brought into the capital, suggesting that the conflict over Susa had begun possibly in the winter of 540 BCE.

It is probable that Cyrus negotiated with the Babylonian generals to obtain a compromise on their part and therefore avoid an armed confrontation. Nabonidus was staying in the city at the time and soon fled to the capital, Babylon, which he had not visited in years. Cyrus' conquest of Susa and the rest of Babylonia commenced a fundamental shift, bringing Susa under Persian control for the first time.

Under Cyrus' son Cambyses II, Susa became a center of political power as one of 4 capitals of the Achaemenid Persian empire, while reducing the significance of Pasargadae as the capital of Persis. Following Cambyses' brief rule, Darius the Great began a major building program in Susa and Persepolis,which included building a large palace. During this time he describes his new capital in the DSf inscription :

"This palace which I built at Susa, from afar its ornamentation was brought. Downward the earth was dug, until I reached rock in the earth. When the excavation had been made, then rubble was packed down, some 40 cubits in depth, another part 20 cubits in depth. On that rubble the palace was constructed." Susa continued as a winter capital and residence for Achaemenid kings succeeding Darius the Great, Xerxes I, and their successors.

The city forms the setting of The Persians (472 BCE), an Athenian tragedy by the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus that is the oldest surviving play in the history of theatre.

Events mentioned in the Old Testament book of Esther are said to have occurred in Susa during the Achaemenid period.

Seleucid period :

The marriages of Stateira II to Alexander the Great of Macedon and her sister, Drypteis, to Hephaestion at Susa in 324 BCE, as depicted in a late-19th-century engraving Susa lost much of its importance after the invasion of Alexander the Great of Macedon in 331 BCE. In 324 BCE he met Nearchus here, who explored the Persian Gulf [citation needed] as he returned from the Indus River by sea. In that same year Alexander celebrated in Susa with a mass wedding between the Persians and Macedonians.

The city retained its importance under the Seleucids for approximately one century after Alexander, however Susa lost its position of imperial capital to Seleucia to become the regional capital of the satrapy of Susiana. Nevertheless, Susa retained its economic importance to the empire with its vast assortment of merchants conducting trade in Susa, using Charax Spasinou as its port.

Seleucus I Nicator minted coins there in substantial quantities. Susa is rich in Greek inscriptions, [citation needed] perhaps indicating a significant number of Greeks living in the city. Especially in the royal city large, well-equipped peristyle houses have been excavated.

Parthian

period :

Susa was a frequent place of refuge for Parthian and later, the Persian Sassanid kings, as the Romans sacked Ctesiphon five different times between 116 and 297 CE. Susa was briefly captured in 116 CE by the Roman emperor Trajan during the course of his Parthian campaign. Never again would the Roman Empire advance so far to the east.

Sassanid

period :

Under the Sassanids, following the founding of Gundeshapur Susa slowly lost its importance. Archaeologically, the Sassanid city is less dense compared to the Parthian period, but there were still significant buildings, with the settlement extending over 400 hectares. Susa was also still very significant economically and a trading center, especially in gold trading. Coins also continued to be minted in the city. The city had a Christian community in a separate district with a Nestorian bishop, whose last representative is attested to in 1265. Archaeologically a stucco panel with the image of a Christian saint has been found.

During the reign of Shapur II after Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire in 312, and the identification of Christians as possible collaborators with the enemy Christians living in the Sasanian Empire were persecuted from 339 onwards. Shapur II also imposed a double tax on the Christians during his war campaign against the Romans. Following a rebellion of Christians living in Susa, the king destroyed the city in 339 using 300 elephants. He later had the city rebuilt and resettled with prisoners of war and weavers, which is believed to have been after his victory over the Romans in Amida in 359. The weaver produced silk brocade. He renamed it Eran-Khwarrah-Shapur ("Iran's glory [built by] Shapur").

Islamic

period :

A group of Western and Iranian Archaeologists at a conference held

in Susa, Khuzestan, Iran in 1977. Henry Wright, William Sumner,

Elizabeth Carter, Genevieve Dolfus, Greg Johnson, Saeid Ganjavi,

Yousef Majidzadeh, Vanden Berghe, ...

In the other story, once again the Muslims were taunted from the city wall that only an Al-Masih ad-Dajjal could capture the city, and since there were none in the besieging army then they may as well give up and go home. One of the Muslim commanders was so angry and frustrated at this taunt that he went up to one of the city gates and kicked it. Instantly the chains snapped, the locks broke and it fell open.

Following their entry into the city, the Muslims killed all of the Persian nobles.

Once the city was taken, as Daniel (Arabic: Danyal) was not mentioned in the Qur'an, nor is he regarded as a prophet in Judaism, the initial reaction of the Muslim was to destroy the cult by confiscating the treasure that had stored at the tomb since the time of the Achaemenids. They then broke open the silver coffin and carried off the mummified corpse, removing from the corpse a signet ring, which carried an image of a man between two lions. However, upon hearing what had happened, the caliph Umar ordered the ring to be returned and the body reburied under the river bed. In time, Daniel became a Muslim cult figure and they as well as Christians began making pilgrimages to the site, despite several other places claiming to be the site of Daniel's grave.

Following the capture of Susa, the Muslims moved on to besiege Gundeshapur.

Susa recovered following its capture and remained a regional center of more than 400 hectares in size. A mosque was built, but also Nestorian bishops are still testifie. In addition, there was a Jewish community with its own synagogue. The city continued to be a manufacturing center of luxury fabrics during this period. Archaeologically, the Islamic period is characterized mainly by its rich ceramics. Beth Huzaye (East Syrian Ecclesiastical Province) had a significant Christian population during the first millennium, and was a diocese of the Church of the East between the 5th and 13th centuries, in the metropolitan province of Beth Huzaye (Elam).

In 1218, the city was razed by invading Mongols and was never able to regain its previous importance. The city further degraded in the 15th century when the majority of its population moved to Dezful.

Today

:

World

Heritage listing :

Gallery :

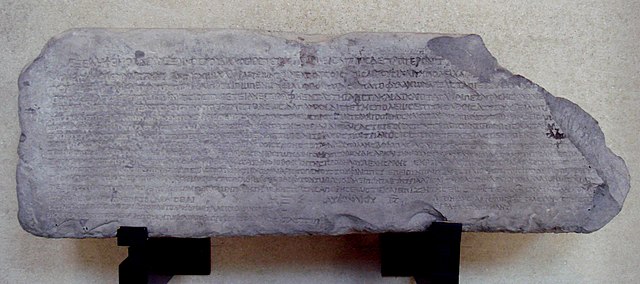

Letter in Greek of the Parthian king Artabanus II to the inhabitants of Susa in the 1st century CE (the city retained Greek institutions since the time of the Seleucid empire). Louvre Museum

Glazed clay cup: Cup with rose petals, 8th–9th centuries

Anthropoid sarcophagus

Lion on a decorative panel from Darius I the Great's palace

Marble head representing Seleucid King Antiochus III who was born near Susa around 242 BC

Glazed clay vase: Vase with palmtrees, 8th–9th centuries

Winged sphinx from the palace of Darius the Great at Susa

Tomb of Daniel

Ninhursag with the spirit of the forests next to the seven-spiked cosmic tree of life. Relief from Susa

19th-century engraving of Daniel's tomb in Susa, from Voyage en Perse Moderne, by Flandin and Coste

Archers frieze from Darius' palace at Susa. Detail of the beginning of the frieze, left. Louvre Museum

Ribbed torc with lion heads, Achaemenid artwork, excavated by Jacques de Morgan, 1901, found in the Acropole Tomb

Shush Castle, 2011

Children in Susa

Herm pillar with Hermes, from the well of the "Dungeon" in Susa Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

,_late_1st_century_BC%96early_1st_century_AD,_Louvre_Museum_(74628.jpg)