| SASSANID PERIOD

Derafsh Kaviani (State flag)

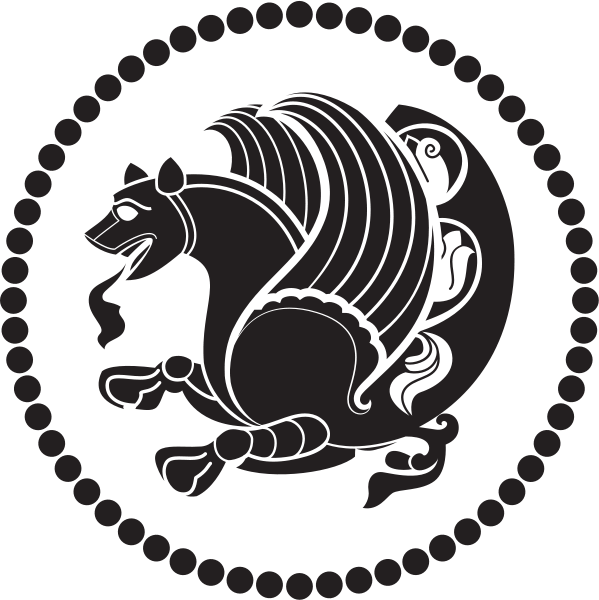

Simurgh (imperial emblem)

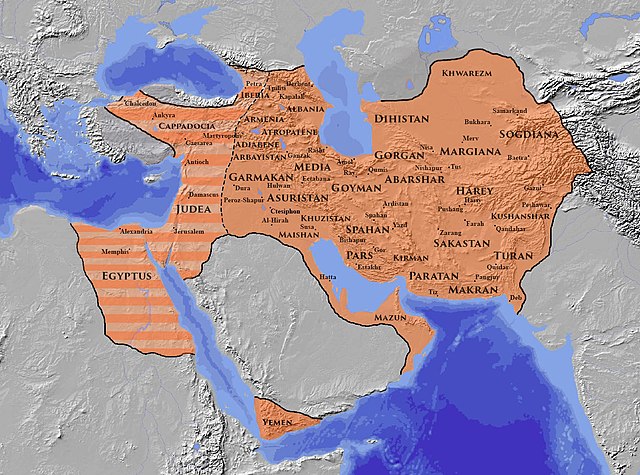

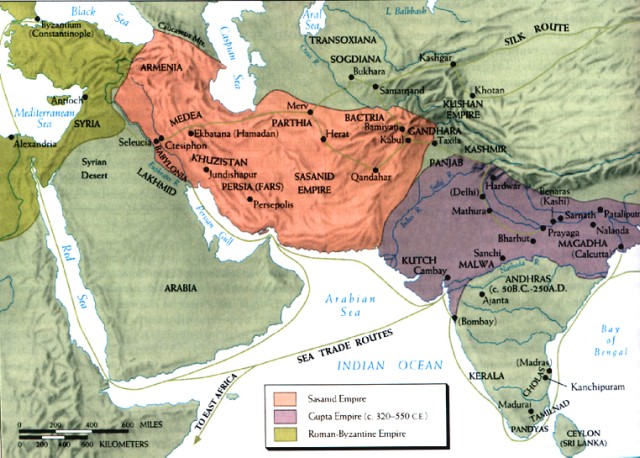

The Sasanian Empire at its greatest extent c. 620, under Khosrow II

Sasanian Empire

Eranshahr

224 - 651

Capital : Istakhr (224 - 226), Ctesiphon (226 - 637)

Common languages : Middle Persian (official), Other languages

Religion : Zoroastrianism (official), Christianity, Judaism, Manichaeism and Mazdakism

Government : Feudal monarchy

Shahanshah

• 224 - 241 : Ardashir I (first)

• 632 - 651 : Yazdegerd III (last)

Historical era : Late Antiquity

• Battle of Hormozdgan : 28 April 224

•

The Iberian War : 526 - 532

• Climactic Roman - Persian War of 602 - 628 : 602 - 628

• Civil war : 628 - 632

• Muslim conquest : 633 - 651

• Empire collapses : 651

Area

550 : 3,500,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi)

Preceded by

Parthian Empire

Kingdom of Iberia (antiquity)

Kushan Empire

Kingdom of Armenia (antiquity)

Kings of Persis

Succeeded

by

Rashidun Caliphate

Dabuyid

dynasty

Bavand

dynasty

Zarmihrids

Masmughans

of Damavand

Qarinvand

dynasty

The

Sasanian Empire or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire

of Iranians (Middle Persian: Eranshahr), and called the Neo-Persian

Empire by historians, was the last Persian imperial dynasty before

the arrival of Islam in the mid seventh century AD. Named after

the House of Sasan, it endured for over four centuries, from 224

to 651 AD, making it the longest-lived Persian dynasty. The Sasanian

Empire succeeded the Parthian Empire, and reestablished the Iranians

as a superpower in late antiquity, alongside its neighbouring arch-rival,

the Roman-Byzantine Empire.

The period of Sasanian rule is considered a high point in Iranian history, and in many ways was the peak of ancient Iranian culture before the Muslim conquest and subsequent Islamisation. The Sasanians tolerated the varied faiths and cultures of their subjects; developed a complex, centralised government bureaucracy; revitalized Zoroastrianism as a legitimising and unifying force of their rule; built grand monuments and public works; and patronised cultural and educational institutions. The empire's cultural influence extended far beyond its territorial borders—including Western Europe, Africa, China and India—and helped shape European and Asian medieval art. Persian culture became the basis for much of Islamic culture, influencing art, architecture, music, literature, and philosophy throughout the Muslim world.

Name

:

More commonly, due to the fact that the ruling dynasty was named after Sasan, the Empire is known as the Sasanian Empire in historical and academic sources. This term is also recorded in English as the Sassanian Empire, the Sasanid Empire and the Sassanid Empire. Historians have also referred to the Sasanian Empire as the Neo-Persian Empire, since it was the second Iranian empire that rose from Pars (Persis); while the Achaemenid Empire was the first one.

History :

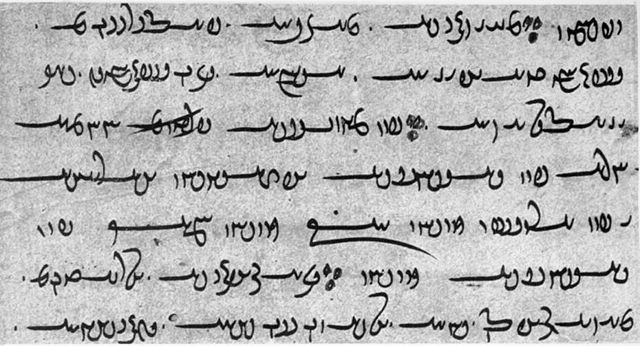

Obv: Bearded facing head, wearing diadem and Parthian-style tiara,

legend "The divine Ardaxir, king" in Pahlavi.

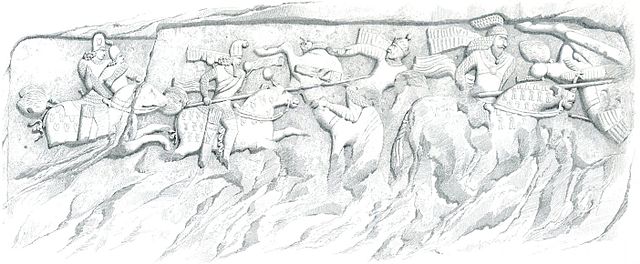

1840 illustration of a Sasanian relief at Firuzabad, showing Ardashir I's victory over Artabanus IV and his forces

Rock relief of Ardashir I receiving the ring of kingship by the Zoroastrian supreme god Ahura Mazda Conflicting accounts shroud the details of the fall of the Parthian Empire and subsequent rise of the Sassanian Empire in mystery. The Sassanian Empire was established in Estakhr by Ardashir I. Papak was originally the ruler of a region called Khir. However, by the year 200 he had managed to overthrow Gochihr and appoint himself the new ruler of the Bazrangids. His mother, Rodhagh, was the daughter of the provincial governor of Pars. Papak and his eldest son Shapur managed to expand their power over all of Pars. The subsequent events are unclear, due to the elusive nature of the sources. It is certain, however, that following the death of Papak, Ardashir, who at the time was the governor of Darabgerd, became involved in a power struggle of his own with his elder brother Shapur. Sources reveal that Shapur, leaving for a meeting with his brother, was killed when the roof of a building collapsed on him. By the year 208, over the protests of his other brothers who were put to death, Ardashir declared himself ruler of Pars.

Once Ardashir was appointed shah (King), he moved his capital further to the south of Pars and founded Ardashir-Khwarrah (formerly Gur, modern day Firuzabad). The city, well protected by high mountains and easily defensible due to the narrow passes that approached it, became the centre of Ardashir's efforts to gain more power. It was surrounded by a high, circular wall, probably copied from that of Darabgird. Ardashir's palace was on the north side of the city; remains of it are extant. After establishing his rule over Pars, Ardashir rapidly extended his territory, demanding fealty from the local princes of Fars, and gaining control over the neighbouring provinces of Kerman, Isfahan, Susiana and Mesene. This expansion quickly came to the attention of Artabanus V, the Parthian king, who initially ordered the governor of Khuzestan to wage war against Ardashir in 224, but Ardashir was victorious in the ensuing battles. In a second attempt to destroy Ardashir, Artabanus himself met Ardashir in battle at Hormozgan, where the former met his death. Following the death of the Parthian ruler, Ardashir went on to invade the western provinces of the now defunct Parthian Empire.

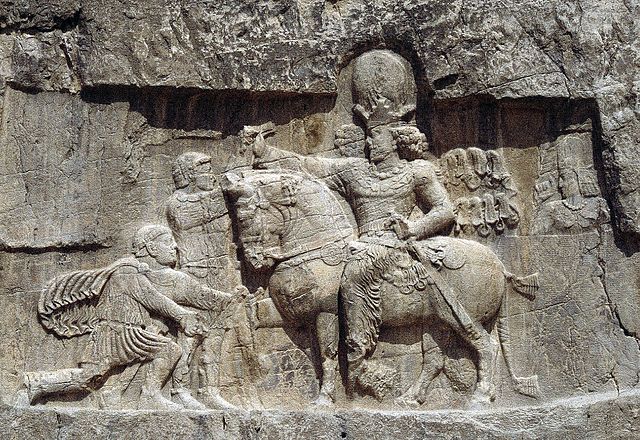

Rock-face relief at Naqsh-e Rostam of Persian emperor Shapur I (on horseback) capturing Roman emperor Valerian (standing) and Philip the Arab (kneeling), suing for peace, following the victory at Edessa At that time the Arsacid dynasty was divided between supporters of Artabanus V and Vologases VI, which probably allowed Ardashir to consolidate his authority in the south with little or no interference from the Parthians. Ardashir was aided by the geography of the province of Fars, which was separated from the rest of Iran. Crowned in 224 at Ctesiphon as the sole ruler of Persia, Ardashir took the title shahanshah, or "King of Kings" (the inscriptions mention Adhur-Anahid as his Banbishnan banbishn, "Queen of Queens", but her relationship with Ardashir has not been fully established), bringing the 400-year-old Parthian Empire to an end, and beginning four centuries of Sassanid rule.

In the next few years, local rebellions occurred throughout the empire. Nonetheless, Ardashir I further expanded his new empire to the east and northwest, conquering the provinces of Sakastan, Gorgan, Khorasan, Marw (in modern Turkmenistan), Balkh and Chorasmia. He also added Bahrain and Mosul to Sassanid's possessions. Later Sassanid inscriptions also claim the submission of the Kings of Kushan, Turan and Makuran to Ardashir, although based on numismatic evidence it is more likely that these actually submitted to Ardashir's son, the future Shapur I. In the west, assaults against Hatra, Armenia and Adiabene met with less success. In 230, Ardashir raided deep into Roman territory, and a Roman counter-offensive two years later ended inconclusively, although the Roman emperor, Alexander Severus, celebrated a triumph in Rome.

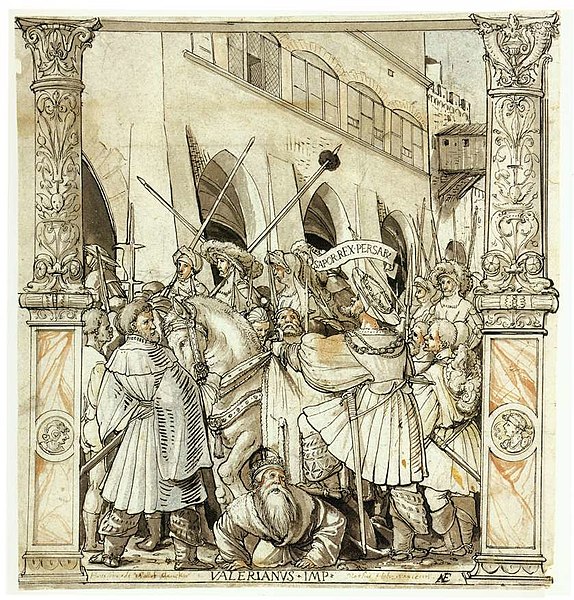

The Humiliation of Valerian by Shapur (Hans Holbein the Younger, 1521, pen and black ink on a chalk sketch, Kunstmuseum Basel) Ardashir I's son Shapur I continued the expansion of the empire, conquering Bactria and the western portion of the Kushan Empire, while leading several campaigns against Rome. Invading Roman Mesopotamia, Shapur I captured Carrhae and Nisibis, but in 243 the Roman general Timesitheus defeated the Persians at Rhesaina and regained the lost territories. The emperor Gordian III's (238–244) subsequent advance down the Euphrates was defeated at Meshike (244), leading to Gordian's murder by his own troops and enabling Shapur to conclude a highly advantageous peace treaty with the new emperor Philip the Arab, by which he secured the immediate payment of 500,000 denarii and further annual payments.

Shapur soon resumed the war, defeated the Romans at Barbalissos (253), and then probably took and plundered Antioch. Roman counter-attacks under the emperor Valerian ended in disaster when the Roman army was defeated and besieged at Edessa and Valerian was captured by Shapur, remaining his prisoner for the rest of his life. Shapur celebrated his victory by carving the impressive rock reliefs in Naqsh-e Rostam and Bishapur, as well as a monumental inscription in Persian and Greek in the vicinity of Persepolis. He exploited his success by advancing into Anatolia (260), but withdrew in disarray after defeats at the hands of the Romans and their Palmyrene ally Odaenathus, suffering the capture of his harem and the loss of all the Roman territories he had occupied.

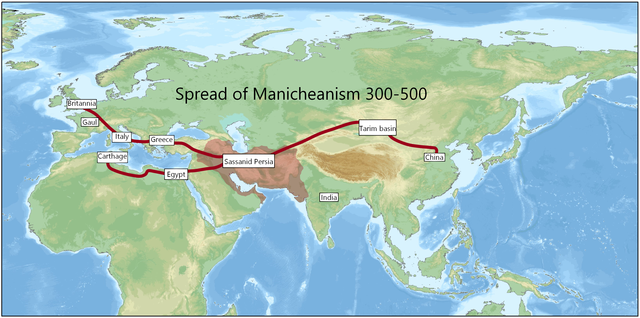

The spread of Manichaeism (300 – 500) Shapur had intensive development plans. He ordered the construction of the first dam bridge in Iran and founded many cities, some settled in part by emigrants from the Roman territories, including Christians who could exercise their faith freely under Sassanid rule. Two cities, Bishapur and Nishapur, are named after him. He particularly favoured Manichaeism, protecting Mani (who dedicated one of his books, the Shabuhragan, to him) and sent many Manichaean missionaries abroad. He also befriended a Babylonian rabbi called Samuel.

This friendship was advantageous for the Jewish community and gave them a respite from the oppressive laws enacted against them. Later kings reversed Shapur's policy of religious tolerance. When Shapur's son Bahram I acceded to the throne, he was pressured by the Zoroastrian high-priest Kartir Bahram I to kill Mani and persecute his followers. Bahram II was also amenable to the wishes of the Zoroastrian priesthood. During his reign, the Sassanid capital Ctesiphon was sacked by the Romans under Emperor Carus, and most of Armenia, after half a century of Persian rule, was ceded to Diocletian.

Succeeding Bahram III (who ruled briefly in 293), Narseh embarked on another war with the Romans. After an early success against the Emperor Galerius near Callinicum on the Euphrates in 296, he was eventually decisively defeated by them. Galerius had been reinforced, probably in the spring of 298, by a new contingent collected from the empire's Danubian holdings. Narseh did not advance from Armenia and Mesopotamia, leaving Galerius to lead the offensive in 298 with an attack on northern Mesopotamia via Armenia. Narseh retreated to Armenia to fight Galerius's force, to the former's disadvantage: the rugged Armenian terrain was favourable to Roman infantry, but not to Sassanid cavalry. Local aid gave Galerius the advantage of surprise over the Persian forces, and, in two successive battles, Galerius secured victories over Narseh.

Rome and satellite kingdom of Armenia around 300, after Narseh's defeat During the second encounter, Roman forces seized Narseh's camp, his treasury, his harem, and his wife. Galerius advanced into Media and Adiabene, winning successive victories, most prominently near Erzurum, and securing Nisibis (Nusaybin, Turkey) before 1 October 298. He then advanced down the Tigris, taking Ctesiphon. Narseh had previously sent an ambassador to Galerius to plead for the return of his wives and children. Peace negotiations began in the spring of 299, with both Diocletian and Galerius presiding.

The conditions of the peace were heavy: Persia would give up territory to Rome, making the Tigris the boundary between the two empires. Further terms specified that Armenia was returned to Roman domination, with the fort of Ziatha as its border; Caucasian Iberia would pay allegiance to Rome under a Roman appointee; Nisibis, now under Roman rule, would become the sole conduit for trade between Persia and Rome; and Rome would exercise control over the five satrapies between the Tigris and Armenia: Ingilene, Sophanene (Sophene), Arzanene (Aghdznik), Corduene, and Zabdicene (near modern Hakkâri, Turkey).

The Sassanids ceded five provinces west of the Tigris, and agreed not to interfere in the affairs of Armenia and Georgia. In the aftermath of this defeat, Narseh gave up the throne and died a year later, leaving the Sassanid throne to his son, Hormizd II. Unrest spread throughout the land, and while the new king suppressed revolts in Sakastan and Kushan, he was unable to control the nobles and was subsequently killed by Bedouins on a hunting trip in 309.

First Golden Era (309–379) :

Bust of Shapur II (r. 309 – 379) Following Hormizd II's death, northern Arabs started to ravage and plunder the western cities of the empire, even attacking the province of Fars, the birthplace of the Sassanid kings. Meanwhile, Persian nobles killed Hormizd II's eldest son, blinded the second, and imprisoned the third (who later escaped into Roman territory). The throne was reserved for Shapur II, the unborn child of one of Hormizd II's wives who was crowned in utero: the crown was placed upon his mother's stomach. During his youth the empire was controlled by his mother and the nobles. Upon his coming of age, Shapur II assumed power and quickly proved to be an active and effective ruler.

He first led his small but disciplined army south against the Arabs, whom he defeated, securing the southern areas of the empire. He then began his first campaign against the Romans in the west, where Persian forces won a series of battles but were unable to make territorial gains due to the failure of repeated sieges of the key frontier city of Nisibis, and Roman success in retaking the cities of Singara and Amida after they had previously fallen to the Persians.

These campaigns were halted by nomadic raids along the eastern borders of the empire, which threatened Transoxiana, a strategically critical area for control of the Silk Road. Shapur therefore marched east toward Transoxiana to meet the eastern nomads, leaving his local commanders to mount nuisance raids on the Romans. He crushed the Central Asian tribes, and annexed the area as a new province.

In the east around 325, Shapur II regained the upper hand against the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom and took control of large territories in areas now known as Afghanistan and Pakistan. Cultural expansion followed this victory, and Sasanian art penetrated Transoxiana, reaching as far as China. Shapur, along with the nomad King Grumbates, started his second campaign against the Romans in 359 and soon succeeded in retaking Singara and Amida. In response the Roman emperor Julian struck deep into Persian territory and defeated Shapur's forces at Ctesiphon. He failed to take the capital, however, and was killed while trying to retreat to Roman territory. His successor Jovian, trapped on the east bank of the Tigris, had to hand over all the provinces the Persians had ceded to Rome in 298, as well as Nisibis and Singara, to secure safe passage for his army out of Persia.

Early Alchon Huns coin based on the coin design of Shapur II, adding the Alchon Tamgha symbol Alchon Tamga.png and "Alchono" in Bactrian script on the obverse. Dated 400–440 From around 370, however, towards the end of the reign of Shapur II, the Sasanians lost the control of Bactria to invaders from the north: first the Kidarites, then the Hephthalites and finally the Alchon Huns, who would follow up with the invasion of India. These invaders initially issued coins based on Sasanian designs. Various coins minted in Bactria and based on Sasanian designs are extant, often with busts imitating Sassanian kings Shapur II (r. 309 to 379) and Shapur III (r. 383 to 388), adding the Alchon Tamgha and the name "Alchono" in Bactrian script on the obverse, and with attendants to a fire altar on the reverse.

Shapur II pursued a harsh religious policy. Under his reign, the collection of the Avesta, the sacred texts of Zoroastrianism, was completed, heresy and apostasy were punished, and Christians were persecuted. The latter was a reaction against the Christianization of the Roman Empire by Constantine the Great. Shapur II, like Shapur I, was amicable towards Jews, who lived in relative freedom and gained many advantages during his reign (see also Raba). At the time of his death, the Persian Empire was stronger than ever, with its enemies to the east pacified and Armenia under Persian control.

Intermediate Era (379 – 498) :

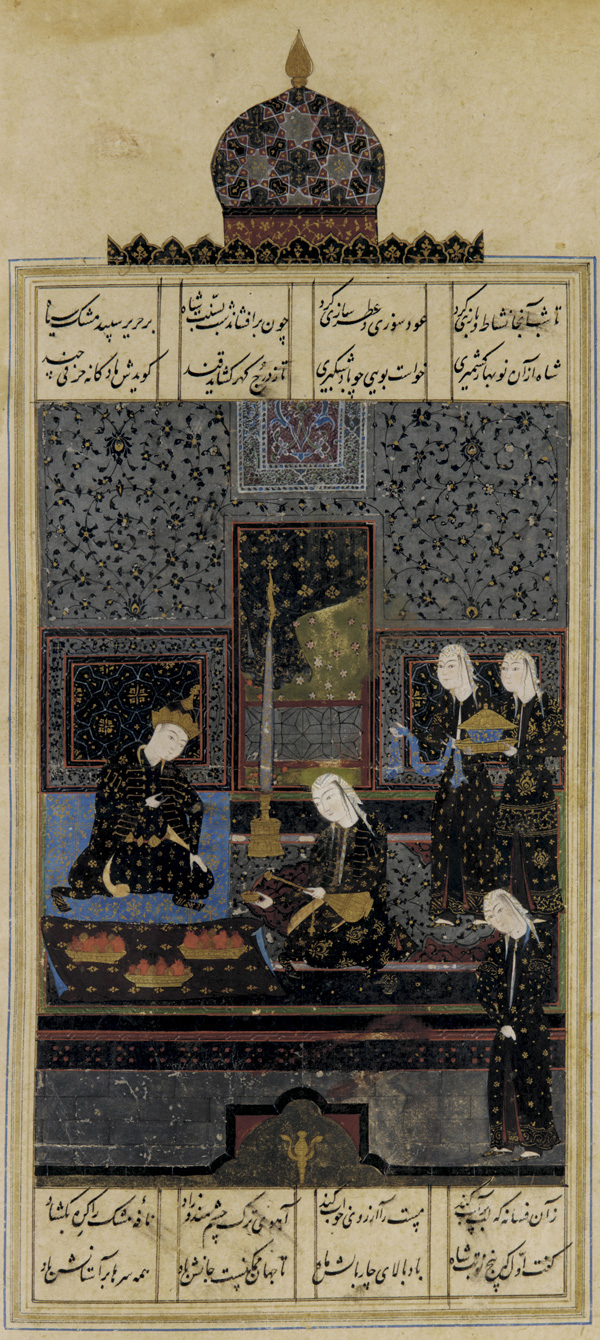

Bahram V is a great favourite in Persian literature and poetry. "Bahram and the Indian princess in the black pavilion." Depiction of a Khamsa (Quintet) by the great Persian poet Nizami, mid-16th-century Safavid era. (at

the bottom of the above Photo there is a trident / trishul seen)

After Shapur II died in 379, the empire passed on to his half-brother Ardashir II (379–383; son of Hormizd II) and his son Shapur III (383–388), neither of whom demonstrated their predecessor's skill in ruling. Ardashir, who was raised as the "half-brother" of the emperor, failed to fill his brother's shoes, and Shapur was too much of a melancholy character to achieve anything. Bahram IV (388–399), although not as inactive as his father, still failed to achieve anything important for the empire. During this time Armenia was divided by a treaty between the Roman and Sasanian empires. The Sasanians reestablished their rule over Greater Armenia, while the Byzantine Empire held a small portion of western Armenia.

Bahram IV's son Yazdegerd I (399–421) is often compared to Constantine I. Both were physically and diplomatically powerful, opportunistic, practiced religious tolerance and provided freedom for the rise of religious minorities. Yazdegerd stopped the persecution against the Christians and punished nobles and priests who persecuted them. His reign marked a relatively peaceful era with the Romans, and he even took the young Theodosius II (408–450) under his guardianship. Yazdegerd also married a Jewish princess, who bore him a son called Narsi.

Yazdegerd I's successor was his son Bahram V (421–438), one of the most well-known Sasanian kings and the hero of many myths. These myths persisted even after the destruction of the Sasanian Empire by the Arabs. Bahram gained the crown after Yazdegerd's sudden death (or assassination), which occurred when the grandees opposed the king with the help of al-Mundhir, the Arabic dynast of al-Hirah. Bahram's mother was Shushandukht, the daughter of the Jewish Exilarch. In 427, he crushed an invasion in the east by the nomadic Hephthalites, extending his influence into Central Asia, where his portrait survived for centuries on the coinage of Bukhara (in modern Uzbekistan). Bahram deposed the vassal king of the Iranian-held area of Armenia and made it a province of the empire.

There are many stories that tell of Bahram V's valour, his beauty, and his victories over the Romans, Turkic peoples, Indians and Africans, as well as his exploits in hunting and his pursuits of love. He was better known as Bahram-e Gur, Gur meaning onager, on account of his love for hunting and, in particular, hunting onagers. He symbolised a king at the height of a golden age, embodying royal prosperity. He had won his crown by competing with his brother and spent much time fighting foreign enemies, but mostly he kept himself amused by hunting, holding court parties and entertaining a famous band of ladies and courtiers. During his time, the best pieces of Sassanid literature were written, notable pieces of Sassanid music were composed, and sports such as polo became royal pastimes.

A coin of Yazdegerd II Bahram V's son Yazdegerd II (438–457) was in some ways a moderate ruler, but, in contrast to Yazdegerd I, he practised a harsh policy towards minority religions, particularly Christianity. However, at the Battle of Avarayr in 451, the Armenian subjects led by Vardan Mamikonian reaffirmed Armenia's right to profess Christianity freely. This was to be later confirmed by the Nvarsak Treaty (484).

At the beginning of his reign in 441, Yazdegerd II assembled an army of soldiers from various nations, including his Indian allies, and attacked the Byzantine Empire, but peace was soon restored after some small-scale fighting. He then gathered his forces in Nishapur in 443 and launched a prolonged campaign against the Kidarites. After a number of battles he crushed them and drove them out beyond the Oxus river in 450. During his eastern campaign, Yazdegerd II grew suspicious of the Christians in the army and expelled them all from the governing body and army. He then persecuted the Christians in his land, and, to a much lesser extent, the Jews. In order to reestablish Zoroastrianism in Armenia, he crushed an uprising of Armenian Christians at the Battle of Vartanantz in 451. The Armenians, however, remained primarily Christian. In his later years, he was engaged yet again with the Kidarites right up until his death in 457. Hormizd III (457–459), the younger son of Yazdegerd II, then ascended to the throne. During his short rule, he continually fought with his elder brother Peroz I, who had the support of the nobility, and with the Hephthalites in Bactria. He was killed by his brother Peroz in 459.

Plate of Peroz I hunting argali At the beginning of the 5th century, the Hephthalites (White Huns), along with other nomadic groups, attacked Iran. At first Bahram V and Yazdegerd II inflicted decisive defeats against them and drove them back eastward. The Huns returned at the end of the 5th century and defeated Peroz I (457–484) in 483. Following this victory, the Huns invaded and plundered parts of eastern Iran continually for two years. They exacted heavy tribute for some years thereafter.

These attacks brought instability and chaos to the kingdom. Peroz tried again to drive out the Hephthalites, but on the way to Balkh his army was trapped by the Huns in the desert. Peroz was defeated and killed by a Hephthalite army near Balkh. His army was completely destroyed, and his body was never found. Four of his sons and brothers had also died. The main Sasanian cities of the eastern region of Khorasan-Nishapur, Herat and Marw were now under Hephthalite rule. Sukhra, a member of the Parthian House of Karen, one of the Seven Great Houses of Iran, quickly raised a new force and stopped the Hephthalites from achieving further success. Peroz' brother, Balash, was elected as shah by the Iranian magnates, most notably Sukhra and the Mihranid general Shapur Mihran.

Balash (484–488) was a mild and generous monarch, and showed care towards his subjects, including the Christians. However, he proved unpopular among the nobility and clergy who had him deposed after just four years in 488. Sukhra, who had played a key role in Balash's deposition, appointed Peroz' son Kavad I as the new shah of Iran. According to Miskawayh (d. 1030), Sukhra was Kavad's maternal uncle. Kavad I (488–531) was an energetic and reformist ruler. He gave his support to the sect founded by Mazdak, son of Bamdad, who demanded that the rich should divide their wives and their wealth with the poor. By adopting the doctrine of the Mazdakites, his intention evidently was to break the influence of the magnates and the growing aristocracy. These reforms led to his being deposed and imprisoned in the Castle of Oblivion in Khuzestan, and his younger brother Jamasp (Zamaspes) became king in 496. Kavad, however, quickly escaped and was given refuge by the Hephthalite king.

Jamasp (496–498) was installed on the Sassanid throne upon the deposition of Kavad I by members of the nobility. He was a good and kind king; he reduced taxes in order to improve the condition of the peasants and the poor. He was also an adherent of the mainstream Zoroastrian religion, diversions from which had cost Kavad I his throne and freedom. Jamasp's reign soon ended, however, when Kavad I, at the head of a large army granted to him by the Hephthalite king, returned to the empire's capital. Jamasp stepped down from his position and returned the throne to his brother. No further mention of Jamasp is made after the restoration of Kavad I, but it is widely believed that he was treated favourably at the court of his brother.

Second Golden Era (498 – 622) :

Plate of a Sasanian king hunting rams, perhaps Kavad I (r. 488–496, 498–531) The second golden era began after the second reign of Kavad I. With the support of the Hephtalites, Kavad launched a campaign against the Romans. In 502, he took Theodosiopolis in Armenia, but lost it soon afterwards. In 503 he took Amida on the Tigris. In 504, an invasion of Armenia by the western Huns from the Caucasus led to an armistice, the return of Amida to Roman control and a peace treaty in 506. In 521/522 Kavad lost control of Lazica, whose rulers switched their allegiance to the Romans; an attempt by the Iberians in 524/525 to do likewise triggered a war between Rome and Persia.

In 527, a Roman offensive against Nisibis was repulsed and Roman efforts to fortify positions near the frontier were thwarted. In 530, Kavad sent an army under Perozes to attack the important Roman frontier city of Dara. The army was met by the Roman general Belisarius, and, though superior in numbers, was defeated at the Battle of Dara. In the same year, a second Persian army under Mihr-Mihroe was defeated at Satala by Roman forces under Sittas and Dorotheus, but in 531 a Persian army accompanied by a Lakhmid contingent under Al-Mundhir III defeated Belisarius at the Battle of Callinicum, and in 532 an "eternal" peace was concluded. Although he could not free himself from the yoke of the Hephthalites, Kavad succeeded in restoring order in the interior and fought with general success against the Eastern Romans, founded several cities, some of which were named after him, and began to regulate taxation and internal administration.

Plate depicting Khosrow I After the reign of Kavad I, his son Khosrow I, also known as Anushirvan ("with the immortal soul"; ruled 531–579), ascended to the throne. He is the most celebrated of the Sassanid rulers. Khosrow I is most famous for his reforms in the aging governing body of Sassanids. He introduced a rational system of taxation based upon a survey of landed possessions, which his father had begun, and he tried in every way to increase the welfare and the revenues of his empire. Previous great feudal lords fielded their own military equipment, followers, and retainers. Khosrow I developed a new force of dehqans, or "knights", paid and equipped by the central government and the bureaucracy, tying the army and bureaucracy more closely to the central government than to local lords.

Emperor Justinian I (527–565) paid Khosrow I 440,000 pieces of gold as a part of the "eternal peace" treaty of 532. In 540, Khosrow broke the treaty and invaded Syria, sacking Antioch and extorting large sums of money from a number of other cities. Further successes followed: in 541 Lazica defected to the Persian side, and in 542 a major Byzantine offensive in Armenia was defeated at Anglon. Also in 541, Khosrow I entered Lazica at the invitation of its king, captured the main Byzantine stronghold at Petra, and established another protectorate over the country, commencing the Lazic War. A five-year truce agreed to in 545 was interrupted in 547 when Lazica again switched sides and eventually expelled its Persian garrison with Byzantine help; the war resumed but remained confined to Lazica, which was retained by the Byzantines when peace was concluded in 562.

In 565, Justinian I died and was succeeded by Justin II (565–578), who resolved to stop subsidies to Arab chieftains to restrain them from raiding Byzantine territory in Syria. A year earlier, the Sassanid governor of Armenia, Chihor-Vishnasp of the Suren family, built a fire temple at Dvin near modern Yerevan, and he put to death an influential member of the Mamikonian family, touching off a revolt which led to the massacre of the Persian governor and his guard in 571, while rebellion also broke out in Iberia. Justin II took advantage of the Armenian revolt to stop his yearly payments to Khosrow I for the defense of the Caucasus passes.

The Armenians were welcomed as allies, and an army was sent into Sassanid territory which besieged Nisibis in 573. However, dissension among the Byzantine generals not only led to an abandonment of the siege, but they in turn were besieged in the city of Dara, which was taken by the Persians. Capitalizing on this success, the Persians then ravaged Syria, causing Justin II to agree to make annual payments in exchange for a five-year truce on the Mesopotamian front, although the war continued elsewhere. In 576 Khosrow I led his last campaign, an offensive into Anatolia which sacked Sebasteia and Melitene, but ended in disaster: defeated outside Melitene, the Persians suffered heavy losses as they fled across the Euphrates under Byzantine attack. Taking advantage of Persian disarray, the Byzantines raided deep into Khosrow's territory, even mounting amphibious attacks across the Caspian Sea. Khosrow sued for peace, but he decided to continue the war after a victory by his general Tamkhosrow in Armenia in 577, and fighting resumed in Mesopotamia. The Armenian revolt came to an end with a general amnesty, which brought Armenia back into the Sassanid Empire.

Around 570, "Ma 'd-Karib", half-brother of the King of Yemen, requested Khosrow I's intervention. Khosrow I sent a fleet and a small army under a commander called Vahriz to the area near present Aden, and they marched against the capital San'a'l, which was occupied. Saif, son of Mard-Karib, who had accompanied the expedition, became King sometime between 575 and 577. Thus, the Sassanids were able to establish a base in South Arabia to control the sea trade with the east. Later, the south Arabian kingdom renounced Sassanid overlordship, and another Persian expedition was sent in 598 that successfully annexed southern Arabia as a Sassanid province, which lasted until the time of troubles after Khosrow II.

Khosrow I's reign witnessed the rise of the dihqans (literally, village lords), the petty landholding nobility who were the backbone of later Sassanid provincial administration and the tax collection system. Khosrow I was a great builder, embellishing his capital and founding new towns with the construction of new buildings. He rebuilt the canals and restocked the farms destroyed in the wars. He built strong fortifications at the passes and placed subject tribes in carefully chosen towns on the frontiers to act as guardians against invaders. He was tolerant of all religions, though he decreed that Zoroastrianism should be the official state religion, and was not unduly disturbed when one of his sons became a Christian.

15th-century Shahnameh illustration of Hormizd IV seated on his throne After Khosrow I, Hormizd IV (579–590) took the throne. The war with the Byzantines continued to rage intensely but inconclusively until the general Bahram Chobin, dismissed and humiliated by Hormizd, rose in revolt in 589. The following year, Hormizd was overthrown by a palace coup and his son Khosrow II (590–628) placed on the throne. However, this change of ruler failed to placate Bahram, who defeated Khosrow, forcing him to flee to Byzantine territory, and seized the throne for himself as Bahram VI. Khosrow asked the Byzantine Emperor Maurice (582–602) for assistance against Bahram, offering to cede the western Caucasus to the Byzantines. To cement the alliance, Khosrow also married Maurice's daughter Miriam. Under the command of Khosrow and the Byzantine generals Narses and John Mystacon, the new combined Byzantine-Persian army raised a rebellion against Bahram, defeating him at the Battle of Blarathon in 591. When Khosrow was subsequently restored to power he kept his promise, handing over control of western Armenia and Caucasian Iberia.

Coin of Khosrow II The new peace arrangement allowed the two empires to focus on military matters elsewhere: Khosrow focused on the Sassanid Empire's eastern frontier while Maurice restored Byzantine control of the Balkans. Circa 600, the Hephthalites had been raiding the Sassanid Empire as far as Spahan in central Iran. The Hephthalites issued numerous coins imitating the coinage of Khosrow II. In c. 606/607, Khosrow recalled Smbat IV Bagratuni from Persian Armenia and sent him to Iran to repel the Hephthalites. Smbat, with the aid of a Persian prince named Datoyean, repelled the Hephthalites from Persia, and plundered their domains in eastern Khorasan, where Smbat is said to have killed their king in single combat.

After Maurice was overthrown and killed by Phocas (602–610) in 602, however, Khosrow II used the murder of his benefactor as a pretext to begin a new invasion, which benefited from continuing civil war in the Byzantine Empire and met little effective resistance. Khosrow's generals systematically subdued the heavily fortified frontier cities of Byzantine Mesopotamia and Armenia, laying the foundations for unprecedented expansion. The Persians overran Syria and captured Antioch in 611.

In 613, outside Antioch, the Persian generals Shahrbaraz and Shahin decisively defeated a major counter-attack led in person by the Byzantine emperor Heraclius. Thereafter, the Persian advance continued unchecked. Jerusalem fell in 614, Alexandria in 619, and the rest of Egypt by 621. The Sassanid dream of restoring the Achaemenid boundaries was almost complete, while the Byzantine Empire was on the verge of collapse. This remarkable peak of expansion was paralleled by a blossoming of Persian art, music, and architecture.

Decline

and fall (622–651) :

The Siege of Constantinople in 626 by the combined Sassanid, Avar, and Slavic forces depicted on the murals of the Moldovita Monastery, Romania In response, Khosrau, in coordination with Avar and Slavic forces, launched a siege on the Byzantine capital of Constantinople in 626. The Sassanids, led by Shahrbaraz, attacked the city on the eastern side of the Bosphorus, while his Avar and Slavic allies invaded from the western side. Attempts to ferry the Persian forces across the Bosphorus to aid their allies (the Slavic forces being by far the most capable in siege warfare) were blocked by the Byzantine fleet, and the siege ended in failure. In 627–628, Heraclius mounted a winter invasion of Mesopotamia, and, despite the departure of his Khazar allies, defeated a Persian army commanded by Rhahzadh in the Battle of Nineveh. He then marched down the Tigris, devastating the country and sacking Khosrau's palace at Dastagerd. He was prevented from attacking Ctesiphon by the destruction of the bridges on the Nahrawan Canal and conducted further raids before withdrawing up the Diyala into north-western Iran.

Queen Boran, daughter of Khosrau II, the first woman and one of the last rulers on the throne of the Sasanian Empire, she reigned from 17 June 629 to 16 June 630 The impact of Heraclius's victories, the devastation of the richest territories of the Sassanid Empire, and the humiliating destruction of high-profile targets such as Ganzak and Dastagerd fatally undermined Khosrau's prestige and his support among the Persian aristocracy. In early 628, he was overthrown and murdered by his son Kavadh II (628), who immediately brought an end to the war, agreeing to withdraw from all occupied territories. In 629, Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic ceremony. Kavadh died within months, and chaos and civil war followed. Over a period of four years and five successive kings, the Sassanid Empire weakened considerably. The power of the central authority passed into the hands of the generals. It would take several years for a strong king to emerge from a series of coups, and the Sassanids never had time to recover fully.

Extent of the Sasanian Empire in 632 with modern borders superimposed In early 632, a grandson of Khosrau I, who had lived in hiding in Estakhr, Yazdegerd III, acceded to the throne. The same year, the first raiders from the Arab tribes, newly united by Islam, arrived in Persian territory. According to Howard-Johnston, years of warfare had exhausted both the Byzantines and the Persians. The Sassanids were further weakened by economic decline, heavy taxation, religious unrest, rigid social stratification, the increasing power of the provincial landholders, and a rapid turnover of rulers, facilitating the Islamic conquest of Persia.

The Sassanids never mounted a truly effective resistance to the pressure applied by the initial Arab armies. Yazdegerd was a boy at the mercy of his advisers and incapable of uniting a vast country crumbling into small feudal kingdoms, despite the fact that the Byzantines, under similar pressure from the newly expansive Arabs, were no longer a threat. Caliph Abu Bakr's commander Khalid ibn Walid, once one of Muhammad's chosen companions-in-arms and leader of the Arab army, moved to capture Iraq in a series of lightning battles. Redeployed to the Syrian front against the Byzantines in June 634, Khalid's successor in Iraq failed him, and the Muslims were defeated in the Battle of the Bridge in 634. However, the Arab threat did not stop there and reemerged shortly via the disciplined armies of Khalid ibn Walid.

Umayyad Caliphate coin imitating Khosrau II. Coin of the time of

Mu'awiya I ibn Abi Sufyan. BCRA (Basra) mint; "Ubayd Allah

ibn Ziyad, governor". Dated AH 56 = 675/6. Sasanian style bust

imitating Khosrau II right; bismillah and three pellets in margin;

c/m: winged creature right / Fire altar with ribbons and attendants;

star and crescent flanking flames; date to left, mint name to right.

Upon hearing of the defeat in Nihawand, Yazdegerd along with Farrukhzad and some of the Persian nobles fled further inland to the eastern province of Khorasan. Yazdegerd was assassinated by a miller in Merv in late 651, while some of the nobles settled in Central Asia, where they contributed greatly to spreading the Persian culture and language in those regions and to the establishment of the first native Iranian Islamic dynasty, the Samanid dynasty, which sought to revive Sassanid traditions.

The abrupt fall of the Sassanid Empire was completed in a period of just five years, and most of its territory was absorbed into the Islamic caliphate; however, many Iranian cities resisted and fought against the invaders several times. Islamic caliphates repeatedly suppressed revolts in cities such as Rey, Isfahan, and Hamadan. The local population was initially under little pressure to convert to Islam, remaining as dhimmi subjects of the Muslim state and paying a jizya. In addition, the old Sassanid "land tax" (known in Arabic as Kharaj) was also adopted. Caliph Umar is said to have occasionally set up a commission to survey the taxes, to judge if they were more than the land could bear.

Descendants

:

•

The Dabuyid dynasty (642–760) descendant of Jamasp.

On a smaller scale, the territory might also be ruled by a number of petty rulers from a noble family, known as shahrdar, overseen directly by the shahanshah. The districts of the provinces were ruled by a shahrab and a mowbed (chief priest). The mowbed's job was to deal with estates and other things relating to legal matters. Sasanian rule was characterized by considerable centralization, ambitious urban planning, agricultural development, and technological improvements. Below the king, a powerful bureaucracy carried out much of the affairs of government; the head of the bureaucracy was the wuzurg framadar (vizier or prime minister). Within this bureaucracy the Zoroastrian priesthood was immensely powerful. The head of the Magi priestly class, the mowbedan mowbed, along with the commander-in-chief, the spahbed, the head of traders and merchants syndicate Ho Tokhshan Bod and minister of agriculture (wastaryoshan-salar), who was also head of farmers, were, below the emperor, the most powerful men of the Sassanid state.

The Sassanian rulers always considered the advice of their ministers. A Muslim historian, Masudi, praised the "excellent administration of the Sasanian kings, their well-ordered policy, their care for their subjects, and the prosperity of their domains". In normal times, the monarchical office was hereditary, but might be transferred by the king to a younger son; in two instances the supreme power was held by queens. When no direct heir was available, the nobles and prelates chose a ruler, but their choice was restricted to members of the royal family.

The Sasanian nobility was a mixture of old Parthian clans, Persian aristocratic families, and noble families from subjected territories. Many new noble families had risen after the dissolution of the Parthian dynasty, while several of the once-dominant Seven Parthian clans remained of high importance. At the court of Ardashir I, the old Arsacid families of the House of Karen and the House of Suren, along with several other families, the Varazes and Andigans, held positions of great honor. Alongside these Iranian and non-Iranian noble families, the kings of Merv, Abarshahr, Kirman, Sakastan, Iberia, and Adiabene, who are mentioned as holding positions of honor amongst the nobles, appeared at the court of the shahanshah. Indeed, the extensive domains of the Surens, Karens and Varazes, had become part of the original Sassanid state as semi-independent states. Thus, the noble families that attended at the court of the Sassanid empire continued to be ruling lines in their own right, although subordinate to the shahanshah.

In general, Wuzurgan from Iranian families held the most powerful positions in the imperial administration, including governorships of border provinces (marzban). Most of these positions were patrimonial, and many were passed down through a single family for generations. The marzbans of greatest seniority were permitted a silver throne, while marzbans of the most strategic border provinces, such as the Caucasus province, were allowed a golden throne. In military campaigns, the regional marzbans could be regarded as field marshals, while lesser spahbeds could command a field army.

Culturally, the Sassanids implemented a system of social stratification. This system was supported by Zoroastrianism, which was established as the state religion. Other religions appear to have been largely tolerated, although this claim has been debated. Sassanid emperors consciously sought to resuscitate Persian traditions and to obliterate Greek cultural influence.

Sasanian military :

The active army of the Sassanid Empire originated from Ardashir I, the first shahanshah of the empire. Ardashir restored the Achaemenid military organizations, retained the Parthian cavalry model, and employed new types of armour and siege warfare techniques.

Role

of priests :

Infantry :

Sasanian army helmet The Paygan formed the bulk of the Sassanid infantry, and were often recruited from the peasant population. Each unit was headed by an officer called a "Paygan-salar", which meant "commander of the infantry" and their main task was to guard the baggage train, serve as pages to the Asvaran (a higher rank), storm fortification walls, undertake entrenchment projects, and excavate mines.

Those serving in the infantry were fitted with shields and lances. To make the size of their army larger, the Sassanids added soldiers provided by the Medes and the Dailamites to their own. The Medes provided the Sassanid army with high-quality javelin throwers, slingers and heavy infantry. Iranian infantry are described by Ammianus Marcellinus as "armed like gladiators" and "obey orders like so many horse-boys". The Dailamite people also served as infantry and were Iranian people who lived mainly within Gilan, Iranian Azerbaijan and Mazandaran. They are reported as having fought with weapons such as daggers, swords and javelins and reputed to have been recognized by Romans for their skills and hardiness in close-quarter combat. One account of Dailamites recounted their participation in an invasion of Yemen where 800 of them were led by the Dailamite officer Vahriz. Vahriz would eventually defeat the Arab forces in Yemen and its capital Sana'a making it a Sasanian vassal until the invasion of Persia by Arabs.

Navy

:

Cavalry :

A Sassanid king posing as an armored cavalryman, Taq-e Bostan, Iran

Sassanian silver plate showing lance combat between two nobles The cavalry used during the Sassanid Empire were two types of heavy cavalry units: Clibanarii and Cataphracts. The first cavalry force, composed of elite noblemen trained since youth for military service, was supported by light cavalry, infantry and archers. Mercenaries and tribal people of the empire, including the Turks, Kushans, Sarmatians, Khazars, Georgians, and Armenians were included in these first cavalry units. The second cavalry involved the use of the war elephants. In fact, it was their specialty to deploy elephants as cavalry support.

Unlike the Parthians, the Sassanids developed advanced siege engines. The development of siege weapons was a useful weapon during conflicts with Rome, in which success hinged upon the ability to seize cities and other fortified points; conversely, the Sassanids also developed a number of techniques for defending their own cities from attack. The Sassanid army was much like the preceding Parthian army, although some of the Sassanid's heavy cavalry were equipped with lances, while Parthian armies were heavily equipped with bows. The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus's description of Shapur II's clibanarii cavalry manifestly shows how heavily equipped it was, and how only a portion were spear equipped :

All the companies were clad in iron, and all parts of their bodies were covered with thick plates, so fitted that the stiff-joints conformed with those of their limbs; and the forms of human faces were so skillfully fitted to their heads, that since their entire body was covered with metal, arrows that fell upon them could lodge only where they could see a little through tiny openings opposite the pupil of the eye, or where through the tip of their nose they were able to get a little breath. Of these, some who were armed with pikes, stood so motionless that you would have thought them held fast by clamps of bronze.

Horsemen in the Sassanid cavalry lacked a stirrup. Instead, they used a war saddle which had a cantle at the back and two guard clamps which curved across the top of the rider's thighs. This allowed the horsemen to stay in the saddle at all times during the battle, especially during violent encounters.

The Byzantine emperor Maurikios also emphasizes in his Strategikon that many of the Sassanid heavy cavalry did not carry spears, relying on their bows as their primary weapons. However the Taq-i Bustan reliefs and Al-Tabari's famed list of equipment required for dihqan knights which included the lance, provide a contrast. What is certain is that the horseman's paraphernalia was extensive.

The amount of money involved in maintaining a warrior of the Asawaran (Azatan) knightly caste required a small estate, and the Asawaran (Azatan) knightly caste received that from the throne, and in return, were the throne's most notable defenders in time of war.

Relations

with neighboring regimes :

A fine cameo showing an equestrian combat of Shapur I and Roman emperor Valerian in which the Roman emperor is seized following the Battle of Edessa, according to Shapur's own statement, "with our own hand", in 260 The Sassanids, like the Parthians, were in constant hostilities with the Roman Empire. The Sassanids, who succeeded the Parthians, were recognized as one of the leading world powers alongside its neighboring rival the Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire, for a period of more than 400 years. Following the division of the Roman Empire in 395, the Byzantine Empire, with its capital at Constantinople, continued as Persia's principal western enemy, and main enemy in general. Hostilities between the two empires became more frequent. The Sassanids, similar to the Roman Empire, were in a constant state of conflict with neighboring kingdoms and nomadic hordes. Although the threat of nomadic incursions could never be fully resolved, the Sassanids generally dealt much more successfully with these matters than did the Romans, due to their policy of making coordinated campaigns against threatening nomads.

The last of the many and frequent wars with the Byzantines, the climactic Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, which included the siege of the Byzantine capital Constantinople, ended with both rivalling sides having drastically exhausted their human and material resources. Furthermore, social conflict within the Empire had considerably weakened it further. Consequently, they were vulnerable to the sudden emergence of the Islamic Rashidun Caliphate, whose forces invaded both empires only a few years after the war. The Muslim forces swiftly conquered the entire Sasanian Empire and in the Byzantine–Arab Wars deprived the Byzantine Empire of its territories in the Levant, the Caucasus, Egypt, and North Africa. Over the following centuries, half the Byzantine Empire and the entire Sasanian Empire came under Muslim rule.

In general, over the span of the centuries, in the west, Sassanid territory abutted that of the large and stable Roman state, but to the east, its nearest neighbors were the Kushan Empire and nomadic tribes such as the White Huns. The construction of fortifications such as Tus citadel or the city of Nishapur, which later became a center of learning and trade, also assisted in defending the eastern provinces from attack.

In south and central Arabia, Bedouin Arab tribes occasionally raided the Sassanid empire. The Kingdom of Al-Hirah, a Sassanid vassal kingdom, was established to form a buffer zone between the empire's heartland and the Bedouin tribes. The dissolution of the Kingdom of Al-Hirah by Khosrau II in 602 contributed greatly to decisive Sassanid defeats suffered against Bedouin Arabs later in the century. These defeats resulted in a sudden takeover of the Sassanid empire by Bedouin tribes under the Islamic banner.

Sassanian fortress in Derbent, Dagestan. Now inscribed on Russia's UNESCO world heritage list since 2003 In the north, Khazars and the Western Turkic Khaganate frequently assaulted the northern provinces of the empire. They plundered Media in 634. Shortly thereafter, the Persian army defeated them and drove them out. The Sassanids built numerous fortifications in the Caucasus region to halt these attacks, of which perhaps the most notably are the imposing fortifications built in Derbent (Dagestan, North Caucasus, now a part of Russia) that to a large extent, have remained intact up to this day.

On the eastern side of the Caspian Sea, the Sassanians erected the Great Wall of Gorgan, a 200 km-long defensive structure probably aimed to protect the empire from northern peoples, such as the White Huns.

War with Axum :

In 522, before Khosrau's reign, a group of monophysite Axumites led an attack on the dominant Himyarites of southern Arabia. The local Arab leader was able to resist the attack but appealed to the Sassanians for aid, while the Axumites subsequently turned towards the Byzantines for help. The Axumites sent another force across the Red Sea and this time successfully killed the Arab leader and replaced him with an Axumite man to be king of the region.

In 531, Justinian suggested that the Axumites of Yemen should cut out the Persians from Indian trade by maritime trade with the Indians. The Ethiopians never met this request because an Axumite general named Abraha took control of the Yemenite throne and created an independent nation. After Abraha's death one of his sons, Ma'd-Karib, went into exile while his half-brother took the throne. After being denied by Justinian, Ma'd-Karib sought help from Khosrau, who sent a small fleet and army under commander Vahriz to depose the new king of Yemen. After capturing the capital city San'a'l, Ma'd-Karib's son, Saif, was put on the throne.

Justinian was ultimately responsible for Sassanian maritime presence in Yemen. By not providing the Yemenite Arabs support, Khosrau was able to help Ma'd-Karib and subsequently established Yemen as a principality of the Sassanian Empire.

Relations

with China :

On different occasions, Sassanid kings sent their most talented Persian musicians and dancers to the Chinese imperial court at Luoyang during the Jin and Northern Wei dynasties, and to Chang'an during the Sui and Tang dynasties. Both empires benefited from trade along the Silk Road and shared a common interest in preserving and protecting that trade. They cooperated in guarding the trade routes through central Asia, and both built outposts in border areas to keep caravans safe from nomadic tribes and bandits.

Politically, there is evidence of several Sassanid and Chinese efforts in forging alliances against the common enemy, the Hephthalites. Upon the rise of the nomadic Göktürks in Inner Asia, there is also what looks like a collaboration between China and the Sassanids to defuse Turkic advances. Documents from Mt. Mogh talk about the presence of a Chinese general in the service of the king of Sogdiana at the time of the Arab invasions.

Following the invasion of Iran by Muslim Arabs, Peroz III, son of Yazdegerd III, escaped along with a few Persian nobles and took refuge in the Chinese imperial court. Both Peroz and his son Narsieh (Chinese neh-shie) were given high titles at the Chinese court. On at least two occasions, the last possibly in 670, Chinese troops were sent with Peroz in order to restore him to the Sassanid throne with mixed results, one possibly ending in a short rule of Peroz in Sakastan, from which we have some remaining numismatic evidence. Narsieh later attained the position of a commander of the Chinese imperial guards, and his descendants lived in China as respected princes, Sassanian refugees fleeing from the Arab conquest to settle in China. The Emperor of China at this time was Emperor Gaozong of Tang.

Relations with India :

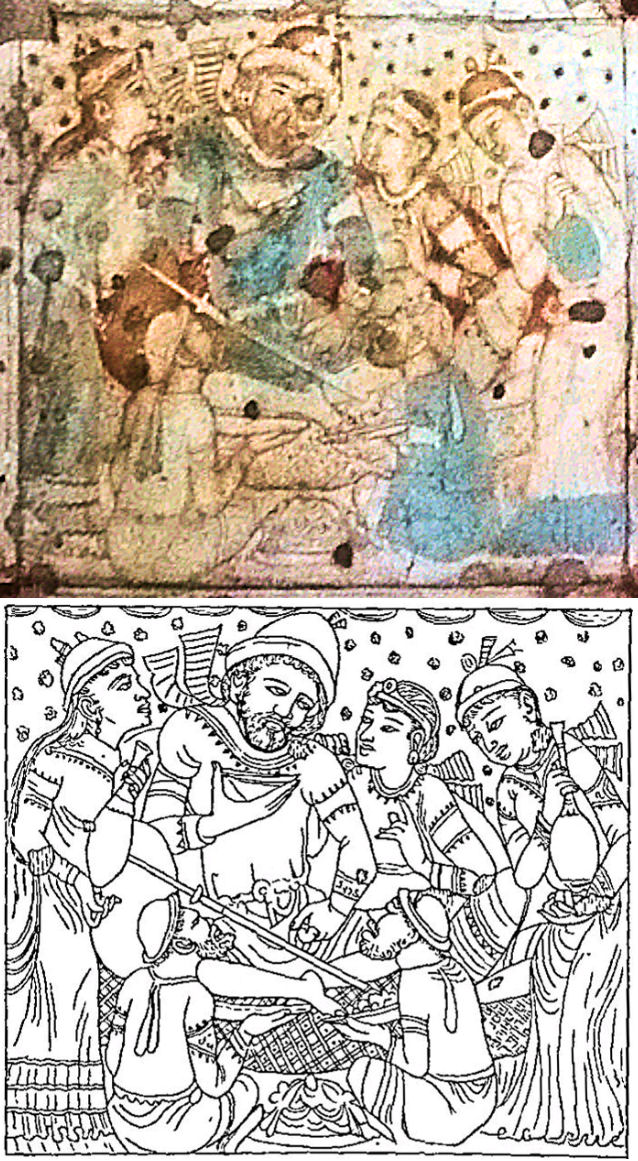

Foreign dignitary drinking wine, on ceiling of Cave 1, at Ajanta Caves, possibly depicting the Sasanian embassy to Indian king Pulakesin II (610–642), photograph and drawing Following the conquest of Iran and neighboring regions, Shapur I extended his authority northwest of the Indian subcontinent. The previously autonomous Kushans were obliged to accept his suzerainty. These were the western Kushans which controlled Afghanistan while the eastern Kushans were active in India. Although the Kushan empire declined at the end of the 3rd century, to be replaced by the Indian Gupta Empire in the 4th century, it is clear that the Sassanids remained relevant in India's northwest throughout this period. [citation needed]

Persia and northwestern India, the latter that made up formerly part of the Kushans, engaged in cultural as well as political intercourse during this period, as certain Sassanid practices spread into the Kushan territories. In particular, the Kushans were influenced by the Sassanid conception of kingship, which spread through the trade of Sassanid silverware and textiles depicting emperors hunting or dispensing justice.

This cultural interchange did not, however, spread Sassanid religious practices or attitudes to the Kushans. Lower-level cultural interchanges also took place between India and Persia during this period. For example, Persians imported the early form of chess, the chaturanga (Middle Persian: chatrang) from India. In exchange, Persians introduced backgammon (New-Ardašer) to India.

During Khosrau I's reign, many books were brought from India and translated into Middle Persian. Some of these later found their way into the literature of the Islamic world and Arabic literature. A notable example of this was the translation of the Indian Panchatantra by one of Khosrau's ministers, Borzuya. This translation, known as the Kalilag ud Dimnag, later made its way into the Arabic literature and Europe. The details of Burzoe's legendary journey to India and his daring acquisition of the Panchatantra are written in full detail in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, which says :

In Indian books, Borzuya read that on a mountain in that land there grows a plant which when sprinkled over the dead revives them. Borzuya asked Khosrau I for permission to travel to India to obtain the plant. After a fruitless search, he was led to an ascetic who revealed the secret of the plant to him: The "plant" was word, the "mountain" learning, and the "dead" the ignorant. He told Borzuya of a book, the remedy of ignorance, called the Kalila, which was kept in a treasure chamber. The king of India gave Borzuya permission to read the Kalila, provided that he did not make a copy of it. Borzuya accepted the condition but each day memorized a chapter of the book. When he returned to his room he would record what he had memorized that day, thus creating a copy of the book, which he sent to Iran. In Iran, Bozorgmehr translated the book into Pahlavi and, at Borzuya's request, named the first chapter after him.

Society

:

The Palace of Taq-i Kisra in Sasanian capital Ctesiphon. The city developed into a rich commercial metropolis. It may have been the most populous city of the world in 570–622 In contrast to Parthian society, the Sassanids renewed emphasis on a charismatic and centralized government. In Sassanid theory, the ideal society could maintain stability and justice, and the necessary instrument for this was a strong monarch. Thus, the Sasanians aimed to be an urban empire, at which they were quite successful. During the late Sasanian period, Mesopotamia had the largest population density in the medieval world. This can be credited to, among other things, the Sasanians founding and re-founding a number of cities, which is talked about in the surviving Middle Persian text Šahrestaniha i Eranšahr (the provincial capitals of Iran). Ardashir I himself built and re-built many cities, which he named after himself, such as Veh-Ardashir in Asoristan, Ardashir-Khwarrah in Pars and Vahman-Ardashir in Meshan. During the Sasanian period, many cities with the name "Iran-khwarrah" were established. This was because Sasanians wanted to revive Avesta ideology.

Many of these cities, both new and old, were populated not only by native ethnic groups, such as the Iranians or Syriacs, but also by the deported Roman prisoners of war, such as Goths, Slavs, Latins, and others. Many of these prisoners were experienced workers, who were used to build things such as cities, bridges, and dams. This allowed the Sasanians to become familiar with Roman technology. The impact these foreigners made on the economy was significant, as many of them were Christians, and the spread of the religion accelerated throughout the empire.

Unlike the amount of information about the settled people of the Sasanian Empire, there is little about the nomadic/unsettled ones. It is known that they were called "Kurds" by the Sasanians, and that they regularly served the Sasanian military, particularly the Dailamite and Gilani nomads. This way of handling the nomads continued into the Islamic period, where the service of the Dailamites and Gilanis continued unabated.

Shahanshah :

Plate of a Sasanian king, located in the Azerbaijan Museum in Iran The head of the Sasanian Empire was the shahanshah (king of kings), also simply known as the shah (king). His health and welfare was of high importance—accordingly, the phrase "May you be immortal" was used to reply to him. The Sasanian coins which appeared from the 6th-century and afterwards depict a moon and sun, which, in the words of the Iranian historian Touraj Daryaee, "suggest that the king was at the center of the world and the sun and moon revolved around him. In effect he was the "king of the four corners of the world", which was an old Mesopotamian idea. The king saw all other rulers, such as the Romans, Turks, and Chinese, as being beneath him. The king wore colorful clothes, makeup, a heavy crown, while his beard was decorated with gold. The early Sasanian kings considered themselves of divine descent; they called themselves "bay" (divine).

When the king went out in public, he was hidden behind a curtain, and had some of his men in front of him, whose duty was to keep the masses away from him and to clear the way. When one came to the king, one was expected to prostrate oneself before him, also known as proskynesis. The king's guards were known as the pushtigban. On other occasions, the king was protected by a discrete group of palace guards, known as the darigan. Both of these groups were enlisted from royal families of the Sasanian Empire, and were under the command of the hazarbed, who was in charge of the king's safety, controlled the entrance of the kings palace, presented visitors to the king, and was allowed military commands or used as a negotiator. The hazarbed was also allowed in some cases to serve as the royal executioner. During Nowruz (Iranian new year) and Mihragan (Mihr's day), the king would hold a speech.

Class

division :

1.

Asronan (priests)

The Sasanian caste system outlived the empire, continuing in the early Islamic period.

Slavery

:

The most common slaves in the Sasanian Empire were the household servants, who worked in private estates and at the fire-temples. Usage of a woman slave in a home was common, and her master had outright control over her and could even produce children with her if he wanted to. Slaves also received wages and were able to have their own families whether they were female or male. Harming a slave was considered a crime, and not even the king himself was allowed to do it.

The master of a slave was allowed to free the person when he wanted to, which, no matter what faith the slave believed in, was considered a good deed. A slave could also be freed if his/her master died.

There was a major school, called the Grand School, in the capital. In the beginning, only 50 students were allowed to study at the Grand School. In less than 100 years, enrollment at the Grand School was over 30,000 students.

Society

:

Art, science and literature :

Horse head, gilded silver, 4th century, Sasanian art

A Sasanian silver plate featuring a simurgh. The mythical bird was used as the royal emblem in the Sasanian period

A Sasanian silver plate depicting a royal lion hunt The Sasanian kings were patrons of letters and philosophy. Khosrau I had the works of Plato and Aristotle, translated into Pahlavi, taught at Gundishapur, and read them himself. During his reign, many historical annals were compiled, of which the sole survivor is the Karnamak-i Artaxshir-i Papakan (Deeds of Ardashir), a mixture of history and romance that served as the basis of the Iranian national epic, the Shahnameh. When Justinian I closed the schools of Athens, seven of their professors went to Persia and found refuge at Khosrau's court. In his treaty of 533 with Justinian, the Sasanian king stipulated that the Greek sages should be allowed to return and be free from persecution.

Under Khosrau I, the Academy of Gundishapur, which had been founded in the 5th century, became "the greatest intellectual center of the time", drawing students and teachers from every quarter of the known world. Nestorian Christians were received there, and brought Syriac translations of Greek works in medicine and philosophy. The medical lore of India, Persia, Syria and Greece mingled there to produce a flourishing school of therapy.

Artistically, the Sasanian period witnessed some of the highest achievements of Iranian civilization. Much of what later became known as Muslim culture, including architecture and writing, was originally drawn from Persian culture. At its peak, the Sasanian Empire stretched from western Anatolia to northwest India (today Pakistan), but its influence was felt far beyond these political boundaries. Sasanian motifs found their way into the art of Central Asia and China, the Byzantine Empire, and even Merovingian France. Islamic art however, was the true heir to Sasanian art, whose concepts it was to assimilate while at the same time instilling fresh life and renewed vigor into it. According to Will Durant :

Sasanian art exported its forms and motifs eastward into India, Turkestan and China, westward into Syria, Asia Minor, Constantinople, the Balkans, Egypt and Spain. Probably its influence helped to change the emphasis in Greek art from classic representation to Byzantine ornament, and in Latin Christian art from wooden ceilings to brick or stone vaults and domes and buttressed walls.

Sasanian carvings at Taq-e Bostan and Naqsh-e Rustam were colored; so were many features of the palaces; but only traces of such painting remain. The literature, however, makes it clear that the art of painting flourished in Sasanian times; the prophet Mani is reported to have founded a school of painting; Firdowsi speaks of Persian magnates adorning their mansions with pictures of Iranian heroes; and the poet al-Buhturi describes the murals in the palace at Ctesiphon. When a Sasanian king died, the best painter of the time was called upon to make a portrait of him for a collection kept in the royal treasury.

Painting, sculpture, pottery, and other forms of decoration shared their designs with Sasanian textile art. Silks, embroideries, brocades, damasks, tapestries, chair covers, canopies, tents and rugs were woven with patience and masterly skill, and were dyed in warm tints of yellow, blue and green. Every Persian but the peasant and the priest aspired to dress above his class; presents often took the form of sumptuous garments; and great colorful carpets had been an appendage of wealth in the East since Assyrian days. The two dozen Sasanian textiles that have survived are among the most highly valued fabrics in existence. Even in their own day, Sasanian textiles were admired and imitated from Egypt to the Far East; and during the Middle Ages, they were favored for clothing the relics of Christian saints. When Heraclius captured the palace of Khosrau II Parvez at Dastagerd, delicate embroideries and an immense rug were among his most precious spoils. Famous was the "Winter Carpet", also known as "Khosrau's Spring" (Spring Season Carpet) of Khosrau Anushirvan, designed to make him forget winter in its spring and summer scenes: flowers and fruits made of inwoven rubies and diamonds grew, in this carpet, beside walks of silver and brooks of pearls traced on a ground of gold. Harun al-Rashid prided himself on a spacious Sasanian rug thickly studded with jewelry. Persians wrote love poems about their rugs.

Studies on Sasanian remains show over 100 types of crowns being worn by Sasanian kings. The various Sasanian crowns demonstrate the cultural, economic, social and historical situation in each period. The crowns also show the character traits of each king in this era. Different symbols and signs on the crowns–the moon, stars, eagle and palm, each illustrate the wearer's religious faith and beliefs.

The Sasanian Dynasty, like the Achaemenid, originated in the province of Pars. The Sasanians saw themselves as successors of the Achaemenids, after the Hellenistic and Parthian interlude, and believed that it was their destiny to restore the greatness of Persia.

In reviving the glories of the Achaemenid past, the Sasanians were no mere imitators. The art of this period reveals an astonishing virility, in certain respects anticipating key features of Islamic art. Sasanian art combined elements of traditional Persian art with Hellenistic elements and influences. The conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great had inaugurated the spread of Hellenistic art into Western Asia. Though the East accepted the outward form of this art, it never really assimilated its spirit. Already in the Parthian period, Hellenistic art was being interpreted freely by the peoples of the Near East. Throughout the Sasanian period, there was reaction against it. Sasanian art revived forms and traditions native to Persia, and in the Islamic period, these reached the shores of the Mediterranean. According to Fergusson :

With the accession of the [Sasanians], Persia regained much of that power and stability to which she had been so long a stranger ... The improvement in the fine arts at home indicates returning prosperity, and a degree of security unknown since the fall of the Achaemenidae.

Surviving palaces illustrate the splendor in which the Sasanian monarchs lived. Examples include palaces at Firuzabad and Bishapur in Fars, and the capital city of Ctesiphon in the Asoristan province (present-day Iraq). In addition to local traditions, Parthian architecture influenced Sasanian architectural characteristics. All are characterized by the barrel-vaulted iwans introduced in the Parthian period. During the Sasanian period, these reached massive proportions, particularly at Ctesiphon. There, the arch of the great vaulted hall, attributed to the reign of Shapur I (241–272), has a span of more than 80 feet (24 m) and reaches a height of 118 feet (36 m). This magnificent structure fascinated architects in the centuries that followed and has been considered one of the most important examples of Persian architecture. Many of the palaces contain an inner audience hall consisting, as at Firuzabad, of a chamber surmounted by a dome. The Persians solved the problem of constructing a circular dome on a square building by employing squinches, or arches built across each corner of the square, thereby converting it into an octagon on which it is simple to place the dome. The dome chamber in the palace of Firuzabad is the earliest surviving example of the use of the squinch, suggesting that this architectural technique was probably invented in Persia.

The unique characteristic of Sasanian architecture was its distinctive use of space. The Sasanian architect conceived his building in terms of masses and surfaces; hence the use of massive walls of brick decorated with molded or carved stucco. Stucco wall decorations appear at Bishapur, but better examples are preserved from Chal Tarkhan near Rey (late Sasanian or early Islamic in date), and from Ctesiphon and Kish in Mesopotamia. The panels show animal figures set in roundels, human busts, and geometric and floral motifs.

At Bishapur, some of the floors were decorated with mosaics showing scenes of banqueting. The Roman influence here is clear, and the mosaics may have been laid by Roman prisoners. Buildings were decorated with wall paintings. Particularly fine examples have been found on Mount Khajeh in Sistan.

Economy :

Sasanian silk twill textile of a simurgh in a beaded surround, 6th–7th century. Used in the reliquary of Saint Len, Paris

Due to the majority of the inhabitants being of peasant stock, the

Sasanian economy relied on farming and agriculture, Khuzestan and

Iraq being the most important provinces for it. The Nahravan Canal

is one of the greatest examples of Sasanian irrigation systems,

and many of these things can still be found in Iran. The mountains

of the Sasanian state were used for lumbering by the nomads of the

region, and the centralized nature of the Sasanian state allowed

it to impose taxes on the nomads and inhabitants of the mountains.

During the reign of Khosrau I, further land was brought under centralized

administration.

Industry and trade :

Sasanian sea trade routes Persian industry under the Sasanians developed from domestic to urban forms. Guilds were numerous. Good roads and bridges, well patrolled, enabled state post and merchant caravans to link Ctesiphon with all provinces; and harbors were built in the Persian Gulf to quicken trade with India. Sasanian merchants ranged far and wide and gradually ousted Romans from the lucrative Indian Ocean trade routes. Recent archeological discovery has shown the interesting fact that Sasanians used special labels (commercial labels) on goods as a way of promoting their brands and distinguish between different qualities.

Khosrau I further extended the already vast trade network. The Sasanian state now tended toward monopolistic control of trade, with luxury goods assuming a far greater role in the trade than heretofore, and the great activity in building of ports, caravanserais, bridges and the like, was linked to trade and urbanization. The Persians dominated international trade, both in the Indian Ocean, Central Asia and South Russia, in the time of Khosrau, although competition with the Byzantines was at times intense. Sassanian settlements in Oman and Yemen testify to the importance of trade with India, but the silk trade with China was mainly in the hands of Sasanian vassals and the Iranian people, the Sogdians.

The main exports of the Sasanians were silk; woolen and golden textiles; carpets and rugs; hides; and leather and pearls from the Persian Gulf. There were also goods in transit from China (paper, silk) and India (spices), which Sasanian customs imposed taxes upon, and which were re-exported from the Empire to Europe.

It was also a time of increased metallurgical production, so Iran earned a reputation as the "armory of Asia". Most of the Sasanian mining centers were at the fringes of the Empire – in Armenia, the Caucasus and above all, Transoxania. The extraordinary mineral wealth of the Pamir Mountains on the eastern horizon of the Sasanian empire led to a legend among the Tajiks, an Iranian people living there, which is still told today. It said that when God was creating the world, he tripped over the Pamirs, dropping his jar of minerals, which spread across the region.

Religion

:

Sassanid Zoroastrianism would develop to have clear distinctions from the practices laid out in the Avesta, the holy books of Zoroastrianism. It is often argued [who?] that the Sassanid Zoroastrian clergy later modified the religion in a way to serve themselves, causing substantial religious uneasiness. [specify] Sassanid religious policies contributed to the flourishing of numerous religious reform movements, most importantly those founded by the influential religious leaders Mani and Mazdak.

The relationship between the Sassanid kings and the religions practiced in their empire became complex and varied. For instance, while Shapur I tolerated and encouraged a variety of religions and seems to have been a Zurvanite himself, religious minorities at times were suppressed under later kings, such as Bahram II. Shapur II, on the other hand, tolerated religious groups except Christians, whom he only persecuted in the wake of Constantine's conversion.

Tansar

and his justification for Ardashir I's rebellion :

Gushnasp had accused Ardashir I of having forsaken tradition by usurping the throne, and that while his actions "may have been good for the World" they were "bad for the faith". Tansar refuted these charges in his letter to Gushnasp by proclaiming that not all of the old ways had been good, and that Ardashir was more virtuous than his predecessors. The Letter of Tansar included some attacks on the religious practices and orientation of the Parthians, who did not follow an orthodox Zoroastrian tradition but rather a heterodox one, and so attempted to justify Ardashir's rebellion against them by arguing that Zoroastrianism had 'decayed' after Alexander's invasion, a decay which had continued under the Parthians and so needed to be 'restored'.

Tansar would later help to oversee the formation of a single 'Zoroastrian church' under the control of the Persian magi, alongside the establishment of a single set of Avestan texts, which he himself approved and authorised.

Influence

of Kartir :

Zoroastrian

calendar reforms under the Sasanians :

Some difficulties arose with the introduction of the first calendar reform, particularly the pushing forward of important Zoroastrian festivals such as Hamaspat-maedaya and Nowruz on the calendar year by year. This confusion apparently caused much distress among ordinary people, and while the Sassanids tried to enforce the observance of these great celebrations on the new official dates, much of the populace continued to observe them on the older, traditional dates, and so parallel celebrations for Nowruz and other Zoroastrian celebrations would often occur within days of each other, in defiance of the new official calendar dates, causing much confusion and friction between the laity and the ruling class. A compromise on this by the Sassanids was later introduced, by linking the parallel celebrations as a 6-day celebration/feast. This was done for all except Nowruz.

A further problem occurred as Nowruz had shifted in position during this period from the spring equinox to autumn, although this inconsistency with the original spring-equinox date for Nowruz had possibly occurred during the Parthian period too.

Further calendar reforms occurred during the later Sassanid era. Ever since the reforms under Ardashir I there had been no intercalation. Thus with a quarter-day being lost each year, the Zoroastrian holy year had slowly slipped backwards, with Nowruz eventually ending up in July. A great council was therefore convened and it was decided that Nowruz be moved back to the original position it had during the Achaemenid period – back to spring. This change probably took place during the reign of Kavad I in the early 6th century. Much emphasis seems to have been placed during this period on the importance of spring and on its connection with the resurrection and Frashegerd.

Three Great Fires :

Ruins of Adur Gushnasp, one of three main Zoroastrian temples in the Sassanian Empire Reflecting the regional rivalry and bias the Sassanids are believed to have held against their Parthian predecessors, it was probably during the Sassanid era that the two great fires in Pars and Media—the Adur Farnbag and Adur Gushnasp respectively—were promoted to rival, and even eclipse, the sacred fire in Parthia, the Adur Burzen-Mehr. The Adur Burzen-Mehr, linked (in legend) with Zoroaster and Vishtaspa (the first Zoroastrian King), was too holy for the Persian magi to end veneration of it completely.

It was therefore during the Sassanid era that the three Great Fires of the Zoroastrian world were given specific associations. The Adur Farnbag in Pars became associated with the magi, Adur Gushnasp in Media with warriors, and Adur Burzen-Mehr in Parthia with the lowest estate, farmers and herdsmen.