| VISHTASP

Vishtasp (Vištaspa, whence "Hystaspes") is the Avestan-language name of a figure of Zoroastrian scripture and tradition, portrayed as an early follower of Zoroaster, and his patron, and instrumental in the diffusion of the prophet's message. Although Vishtasp is not epigraphically attested, he is – like Zoroaster also – traditionally assumed to have been a historical figure, and – again, like Zoroaster – that figure is obscured by accretions from legend and myth.

In Zoroastrian tradition, which builds on allusions found in the Avesta, Vishtasp is a righteous king who helped propagate and defend the faith. In the non-Zoroastrian Sistan cycle texts, Vishtasp is a loathsome ruler of Kayanian dynasty who intentionally sends his eldest son to a certain death. In Greco-Roman literature, Zoroaster's patron was the pseudo-anonymous author of a set of prophecies written under his name.

In

scripture :

The Gathic allusions recur in the Yashts of the Younger Avesta. The appeal to Mazda for a boon reappears in Yasht 5. 98, where the boon is asked for the Haugvan [n 1] and Naotara families, and in which Vishtasp is said to be a member of the latter. [n 2] Later in the same hymn, Zoroaster is described as appealing to Mazda to "bring Vishtaspa, son of Aurvataspa, to think according to Daena (Religion), to speak according to the Religion, to act according to the Religion." (Yt. 5. 104–105). In Yasht 9. 25–26, the last part of which is an adaptation of the Gathic Yasna 49. 7, the prophet makes the same appeal with regard to Hutaosa, wife of Vishtasp.

In Yasht 9. 130, Vishtasp himself appeals for the ability to drive off the attacks of the daeva-worshipping Arejat.aspa and other members of drujvant Hyaona family. Similarly in Yasht 5. 109, Vishtasp pleads for strength that he may "crush Tathryavant of the bad religion, the daeva-worshipper Peshana, and the wicked Arejat.aspa." Elsewhere (Yt. 5. 112–113), Vishtasp also pleads for strength on behalf of Zairivairi (Pahl. Zarer), who in later tradition is said to be Vishtasp's younger brother. The allusions to conflicts (perhaps battles, see below) are again obliquely referred to in Yasht 13. 99–100, in which the fravashis of Zoroaster and Vishtasp are described as victorious combatants for Asha, and the rescuers and furtherers of the religion. This description is repeated in Yasht 19. 84–87, where Zoroaster, Vishtasp and Vishtasp's ancestors are additionally said to possess khvarenah. While the chief hero of the conflicts is said to be Vishtasp's son, Spentodhat, (Yt. 13. 103)[6] in Yasht 13. 100, Vishtasp is proclaimed to have set his adopted faith "in the place of honor" amongst peoples.

Passages in the Frawardin Yasht (Yt. 13. 99–103) and elsewhere have enabled commentators to infer family connections between Vishtasp and several other figures named in the Avesta. The summaries of several lost Avestan texts (Wishtasp sast nask, Spand nask, Chihrdad nask, and Varshtmansar nask), as reported in the Denkard (respectively 8. 11, 8. 13, 8. 14, and 9. 33. 5), suggest that there once existed a detailed "history" of Vishtasp and his ancestors in scripture. The Yasht 13 mentions Zairiuuairi, Piší šiiaotna (Vishtasp's eschatological son Pišišotan), Spentodata (Spandyad), Bastauuairi (Bastwar), Kauuarazman, Frašaoštra and Jamaspa (the Huuoguua brothers in the Gathas), all of whom are featured in the Pahlavi narrative about the war between Vishtasp and Arzasp (Arjasp, king of the Xiiaonas). In Yasht 9.31, Vishtasp prays to Druuaspa that he may successfully fight and kill various opponents and, apparently, turn Humaiia and Varedakana away from the lands of the Xiiaonas.

In Yasna 12, the Zarathustra, Vishtasp, Frašaoštra and Jamaspa, and the three Saošiiants, Zarathustra’s eschatological sons, and in Yasna 23.2 and 26.5, the fravashi of Gaiia Maretan, Zarathustra, Vishtasp, and Isar.vastra (another of Zarathustra’s eschatological sons) are listed as the principal fighters for Asha.

The meaning of Vishtasp's name is uncertain. Interpretations include "'he whose horses have (or horse has) come in ready (for riding, etc.)'";"'he who has trained horses'"; and "'whose horses are released (for the race)'". [n 3] It agrees with the description from Yasht 5.132 in which was a prototypical winner of the chariot race.

In

tradition and folklore

The Yasht's allusions to conflicts are amplified in the 9th–11th century books of Zoroastrian tradition, where the conflicts are portrayed as outright battles of the faith. So for example the surviving fragments of a fragmentary text that celebrates the deeds of Zairivairi, Vishtasp's brother and captain of his forces against Arejat.aspa, chief of the Hyonas. According to that text (Ayadgar i Zareran, 10–11), upon hearing of Vishtasp's conversion, Arejat.aspa sent messengers to demand that Vishtasp" abandon 'the pure Mazda-worshipping religion which he had received from Ohrmazd', and should become once more 'of the same religion'" as himself. The battle that following Vishtasp's refusal left Vishtasp victorious.

The

conversion of Vishtasp is likewise a theme of the 9th–11th

century books, and these legends remain the "best known and

most current" among Zoroastrians today. According to this tradition,

when Zoroaster arrived at Vishtasp's court, the prophet was "met

with hostility from the kayags and karabs (kavis and karapans),

with whom he disputed at a great assembly–a tradition which

may well be based on reality, for [Vishtasp] must have had his own

priests and seers, who would hardly have welcomed a new prophet

claiming divine authority."

In medieval Zoroastrian chronology, Vishtasp is identified as a grandfather of "Ardashir", i.e. the 5th century BCE Artaxerxes I (or II). This myth is tied to the Sassanid (early 3rd–early 7th century) claim of descent from Artaxerxes, and the claim of relationship to the Kayanids, that is, with Vishtasp and his ancestors. The full adoption of Kayanid names, titles and myths from the Avesta by the Sassanids was a "main component of [Sassanid] ideology." The association of Artaxerxes with the Kayanids occurred through the identification of Artaxerxes II's title ('Mnemon' in Greek) with the name of Vishtasp's legendary grandson and successor, Wahman: both are theophorics of Avestan Vohu Manah "Good Mind(ed)"; Middle Persian 'Wahman' is a contraction of the Avestan name, while Greek 'Mnemon' is a calque of it. The Sassanid association of their dynasty with Vishtaspa's is a development dated to the end of the 4th century, and which "arose to some extent because this was when the Sasanians conquered Balkh, the birthplace of Vishtasp and the 'holy land' of Zoroastrianism."[n 7]

As was also the case for the fourth century Roman identification of Zoroaster's patron with the late-6th century BCE father of Darius I (see below) – the identification of Vishtasp as a grandfather of "Ardashir" (Artaxerxes I/II) was once perceived to substantiate the "traditional date" of Zoroaster, which places the prophet in the 6th century BCE. The traditional descriptions of Vishtasp's ancestors as having chariots (a description that puts them fully in the Bronze Age) also contribute to the academic debate on the dating of Zoroaster; for a summary of the role of Vishtasp's ancestors in this issue, see Boyce 1984, p. 62, n. 38. [n 8]

In the Sistan heroic cycle :

Gushtasp

in a section of folio 402 of the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp. The illustration,

dated ca. 1520 and now in the Aga Khan Museum, Toronto (accession

# AKM 00163), is one of six miniatures in the Houghton manuscript

that are attributed to Mirza Ali, the early 16th-century court artist

of the Moghuls.

In several respects, for instance in Goshtasb's/Goshtasf's (etc) mythological genealogy, the Sistan cycle texts continue the Zoroastrian tradition. So, for example, Goshtasp is identified as a member of the Kayanian dynasty, is the son of Lohrasp/Lohrasb (etc), is the brother of Zareh/Zarer (etc), is the father of Esfandiar/Isfandiar (etc) and Bashutan/Beshotan (etc), and so on. However, in the Sistan legends, Goshtasb/Goshtasf (etc.) is an abominable figure, altogether unlike the hero of Zoroastrian tradition. The reason for this discrepancy is unknown. According to the Sistan tradition, Goshtasb demands the throne from his father Lohrasp, but storms off to India ("Hind") when the king declines. Goshtasb's brother Zareh (Zareh/Zarer etc., Avestan Zairivairi) is sent to fetch him, but Goshtasb flees to "Rome" where he marries Katayoun (Katayun/Katayoun etc), the daughter of the 'qaysar'. Goshtasb subsequently becomes a military commander for the Roman emperor, and encourages the emperor to demand tribute from Iran. Again Zareh is sent to fetch Goshtasb, who is then promised the throne, and is thus persuaded to return.

Back in Sistan, Goshtasb imprisons his own son Esfandiar (Esfandiar/Isfandiar etc., Avestan Spentodata), but then has to seek Esfandiar's help in defeating Arjasp (Avestan Aurvatasp) who is threatening Balkh. Goshtasb promises Esfandiar the throne in return for his help, but when Esfandiar is successful, his father stalls and instead sends him off on another mission to suppress a rebellion in Turan. Esfandiar is again successful, and upon his return Goshtasb hedges once again and – aware of a prediction that foretells the death of Esfandiar at the hand of Rostam – sends him off on a mission in which Esfandiar is destined to die. In the Shahnameh, the nobles upbraid Goshtasb as a disgrace to the throne; his daughters denounce him as a heinous criminal; and his younger son Bashutan (Avestan Peshotanu) condemns him as a wanton destroyer of Iran.

As in Zoroastrian tradition, in the Sistan cycle texts Goshtasp is succeeded by Esfandiar's son, Bahman (< MP Wahman). The identification of Bahman with 'Ardashir' (see above) reappears in the Sistan cycle texts as well.

In

Greek and Roman thought :

None of the works attributed to him are still extant, but quotations and references have survived in the works of others, especially in those of two early Christian writers – Justin Martyr (ca. 100 CE) in Samaria and the mid-3rd century Lactantius in North Africa – who drew on them by way of confirmation that what themselves held to be revealed truth had already been uttered.[30] Only one of these pseudepigraphic works – referred to as the Book of Hystaspes or the Oracles of Hystaspes or just Hystaspes – is known by name. This work (or set of works) of the first century BCE is referred to by Lactantius, Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, Lydus, and Aristokritos, all of whom describe it as foretelling the downfall of the Roman empire, the return of rule to the east, and of the coming of the saviour.

Lactantius

provides a detailed summary of the Oracles of Hystaspes in his Divinae

Institutiones (Book VII, from the end of chapter 15 through chapter

19). It begins with Hystaspes awaking from a dream, and needing

to have it interpreted for him. This is duly accomplished by a young

boy, "here representing, according to convention, the openness

of youth and innocent to divine visitations." As interpreted

by the boy, the dream "predicts" the iniquity of the last

age, and the impending destruction of the wicked by fire.

Unlike the works attributed to the other two les Mages hellénisés, the Oracles of Hystaspes was apparently based on the genuine Zoroastrian myths, and "the argument for ultimate magian composition is a strong one. As prophecies they have a political context, a function, and a focus which radically distinguish them from the philosophical and encyclopedic wisdom of the other pseudepigrapha. "Although "[p]rophecies of woes and iniquities in the last age are alien to orthodox Zoroastrianism", there was probably a growth of Zoroastrian literature in the late fourth-early third centuries denouncing the evils of the Hellenistic age, and offering hope of the coming kingdom of Ahura Mazda.

The Greco-Roman obsession with Zoroaster as the "inventor" of astrology also influenced the image of Hystaspes. So for example in Lydus' On the months (de Mensibus II. 4), which credits "the Chaldeans in the circle of Zoroaster and Hystaspes and the Egyptians" for the creation of the seven-day week after the number of planets.

The

fourth century Ammianus Marcellinus (xxiii. 6. 32) identifies Zoroaster's

patron with another Vishtaspa, better known as Hystaspes in English,

the (late-6th century BCE) father of Darius I. The sixth century

Agathias was more ambivalent, observing that it wasn't clear to

him whether the name of Zoroaster's patron referred to the father

of Darius or to another Hystaspes (ii. 24). As with the medieval

Zoroastrian chronology that identifies Vishtasp with "Ardashir"

(see above), Ammianus' identification was once considered to substantiate

the "traditional date" of Zoroaster.

https://en.wikipedia.org/

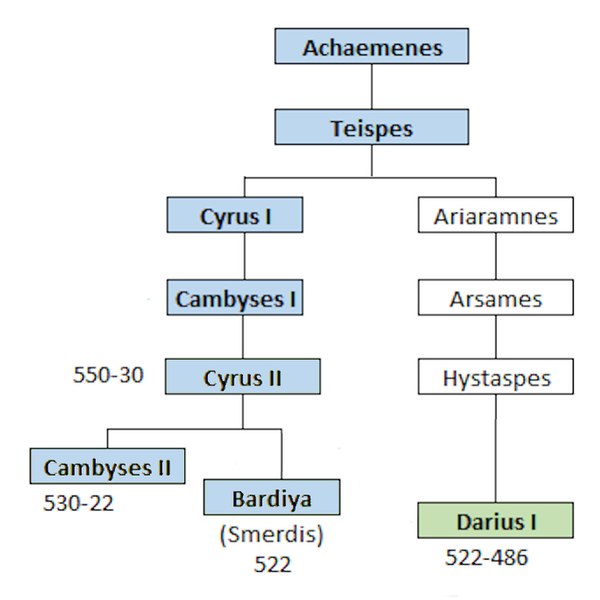

Hystaspes, Vishtaspa (Old Persian : Vištaspa), Vishtap or Gustasp (modern Persian) (fl. 550 BC), was a Persian satrap of Bactria and Persis. He was the father of Darius I, king of the Achaemenid Empire, and Artabanus, who was a trusted advisor to both his brother Darius as well as Darius's son and successor, Xerxes I.

The son of Arsames, Hystaspes was a member of the Persian royal house of the Achaemenids. He was satrap of Persis under Cambyses, and probably under Cyrus the Great also. He accompanied Cyrus on his expedition against the Massagetae. However, he was sent back to Persis to keep watch over his eldest son, Darius, whom Cyrus, after a dream, suspected of considering treason.

Besides Darius, Hystaspes had three sons: Artabanus, Artaphernes, and Artanes, as well as a daughter who married Darius' lance-bearer Gobryas.

Ammianus Marcellinus makes him a chief of the Magians, and tells a story of his studying in India under the Brahmins, an event that would correspond to the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley :

Click here to view Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley.

"Hystaspes, a very wise monarch, the father of Darius. Who while boldly penetrating into the remoter districts of upper India, came to a certain woody retreat, of which with its tranquil silence the Brahmans, men of sublime genius, were the possessors. From their teaching he learnt the principles of the motion of the world and of the stars, and the pure rites of sacrifice, as far as he could; and of what he learnt he infused some portion into the minds of the Magi, which they have handed down by tradition to later ages, each instructing his own children, and adding to it their own system of divination".

—

Ammianus Marcellinus, XXIII. 6.[9]

The name of Hystaspes occurs in the inscriptions at Persepolis and in the Behistun Inscription, where the full lineage of Darius the Great is given:

King

Darius says :

King

Darius says :

King

Darius says :

— Behistun Inscription

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.png)