| INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION

Geographical

range : Basins of the Indus River, Pakistan and the seasonal

Ghaggar-Hakra river, northwest India and eastern Pakistan.

Preceded

by : Mehrgarh

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE. Together with ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, it was one of three early civilisations of the Near East and South Asia, and of the three, the most widespread, its sites spanning an area stretching from northeast Afghanistan, through much of Pakistan, and into western and northwestern India. It flourished in the basins of the Indus River, which flows through the length of Pakistan, and along a system of perennial, mostly monsoon-fed, rivers that once coursed in the vicinity of the seasonal Ghaggar-Hakra river in northwest India and eastern Pakistan.

The civilisation's cities were noted for their urban planning, baked brick houses, elaborate drainage systems, water supply systems, clusters of large non-residential buildings, and new techniques in handicraft (carnelian products, seal carving) and metallurgy (copper, bronze, lead, and tin). The large cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa very likely grew to containing between 30,000 and 60,000 individuals, and the civilisation itself during its florescence may have contained between one and five million individuals.

Gradual drying of the region's soil during the 3rd millennium BCE may have been the initial spur for the urbanisation associated with the civilisation, but eventually weaker monsoons and reduced water supply caused the civilisation's demise, and to scatter its population eastward and southward.

The Indus civilisation is also known as the Harappan Civilisation, after its type site, Harappa, the first of its sites to be excavated early in the 20th century in what was then the Punjab province of British India and now is Pakistan. The discovery of Harappa and soon afterwards Mohenjo-daro was the culmination of work beginning in 1861 with the founding of the Archaeological Survey of India during the British Raj. There were however earlier and later cultures often called Early Harappan and Late Harappan in the same area; for this reason, the Harappan civilisation is sometimes called the Mature Harappan to distinguish it from these other cultures.

By 2002, over 1,000 Mature Harappan cities and settlements had been reported, of which just under a hundred had been excavated, However, there are only five major urban sites: Harappa, Mohenjo-daro (UNESCO World Heritage Site), Dholavira, Ganeriwala in Cholistan, and Rakhigarhi. The early Harappan cultures were preceded by local Neolithic agricultural villages, from which the river plains were populated.

The Harappan language is not directly attested, and its affiliation is uncertain since the Indus script is still undeciphered. A relationship with the Dravidian or Elamo-Dravidian language family is favoured by a section of scholars like leading Finnish Indologist, Asko Parpola.

Excavated ruins of Mohenjo-daro, Sindh province, Pakistan, showing the Great Bath in the foreground. Mohenjo-daro, on the right bank of the Indus River, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the first site in South Asia to be so declared.

Miniature Votive Images or Toy Models from Harappa, c. 2500 BCE. Hand-modeled terra-cotta figurines indicate the yoking of zebu oxen for pulling a cart and the presence of the chicken, a domesticated jungle fowl.

Name

:

Aryan indigenist writers like David Frawley use the terms "Sarasvati culture", the "Sarasvati Civilisation", the "Indus-Sarasvati Civilisation" or the "Sindhu-Saraswati Civilisation", because they consider the Ghaggar-Hakra river to be the same as the Sarasvati, a river mentioned several times in the Rig Ved, a collection of ancient Sanskrit hymns composed in the second millennium BCE. Recent geophysical research suggests that unlike the Sarasvati, whose descriptions in the Rig Veda are those of a snow-fed river, the Ghaggar-Hakra was a system of perennial monsoon-fed rivers, which became seasonal around the time that the civilisation diminished, approximately 4,000 years ago. In addition, proponents of the Sarasvati nomenclature see a connection between the decline of the Indus civilisation and the rise of the Vedic civilisation on the Gangetic plain; however, historians of the decline of the mature Indus civilisation consider the two to be substantially disconnected.

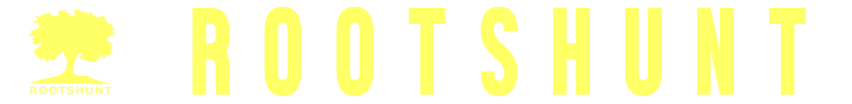

Extent :

Major sites and extent of the Indus Valley Civilization The Indus civilization was roughly contemporary with the other riverine civilisations of the ancient world: Egypt along the Nile, Mesopotamia in the lands watered by the Euphrates and the Tigris, and China in the drainage basin of the Yellow River and the Yangtze. By the time of its mature phase, the civilisation had spread over an area larger than the others, which included a core of 1,500 kilometres (900 mi) up the alluvial plain of the Indus and its tributaries. In addition, there was a region with disparate flora, fauna, and habitats, up to ten times as large, which had been shaped culturally and economically by the Indus.

Around 6500 BCE, agriculture emerged in Balochistan, on the margins of the Indus alluvium. In the following millennia, settled life made inroads into the Indus plains, setting the stage for the growth of rural and urban human settlements. The more organized sedentary life in turn led to a net increase in the birth rate. The large urban centres of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa very likely grew to containing between 30,000 and 60,000 individuals, and during the civilization's florescence, the population of the subcontinent grew to between 4–6 million people. During this period the death rate increased as well, for close living conditions of humans and domesticated animals led to an increase in contagious diseases. According to one estimate, the population of the Indus civilization at its peak may have been between one and five million.

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) extended from Pakistan's Balochistan in the west to India's western Uttar Pradesh in the east, from northeastern Afghanistan in the north to India's Gujarat state in the south. The largest number of sites are in Gujarat, Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir states in India, and Sindh, Punjab, and Balochistan provinces in Pakistan. Coastal settlements extended from Sutkagan Dor in Western Baluchistan to Lothal in Gujarat. An Indus Valley site has been found on the Oxus River at Shortugai in northern Afghanistan, in the Gomal River valley in northwestern Pakistan, at Manda, Jammu on the Beas River near Jammu, India, and at Alamgirpur on the Hindon River, only 28 km (17 mi) from Delhi. The southern most site of the Indus valley civilisation is Daimabad in Maharashtra. Indus Valley sites have been found most often on rivers, but also on the ancient seacoast, for example, Balakot, and on islands, for example, Dholavira.

Discovery and history of excavation :

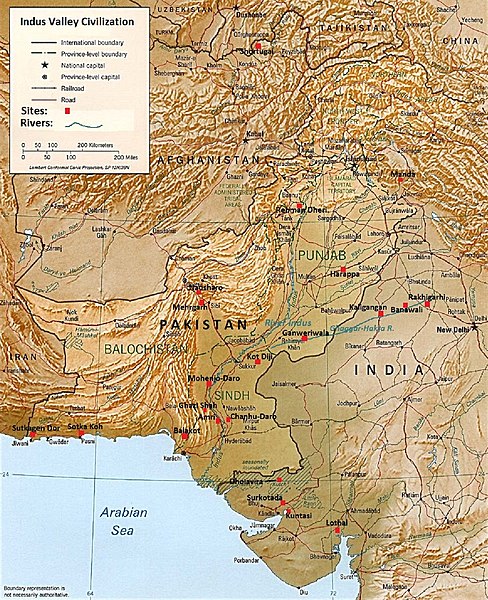

Alexander Cunningham, the first director general of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), interpreted a Harappan stamp seal in 1875.

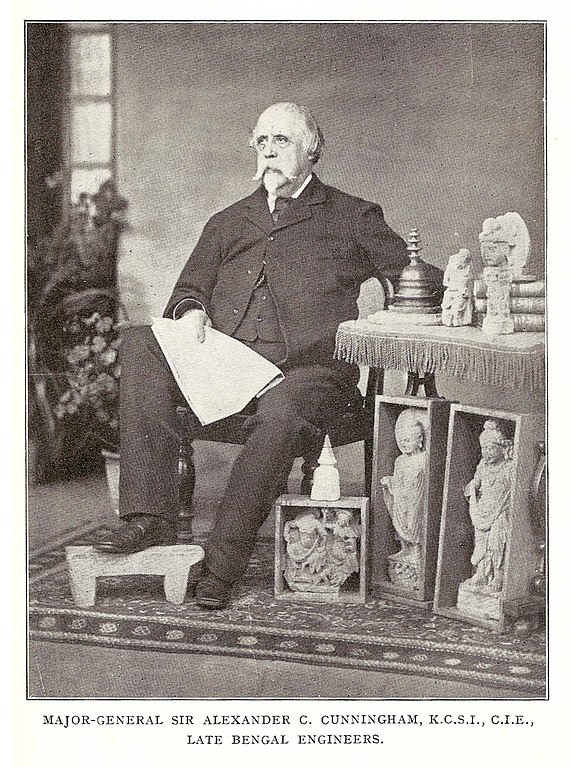

R. D. Banerji, an officer of the ASI, visited Mohenjo-daro in 1919–1920, and again in 1922–1923, postulating the site's far-off antiquity.

John

Marshall, the director-general of the ASI from 1902–1928,

who oversaw the excavations in Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, shown in

a 1906 photograph.

• South Asia (orthographic projection)

Two years later, the Company contracted Alexander Burnes to sail up the Indus to assess the feasibility of water travel for its army. Burnes, who also stopped in Harappa, noted the baked bricks employed in the site's ancient masonry, but noted also the haphazard plundering of these bricks by the local population.

Despite these reports, Harappa was raided even more perilously for its bricks after the British annexation of the Punjab in 1848–49. A considerable number were carted away as track ballast for the railway lines being laid in the Punjab. Nearly 160 km (100 mi) of railway track between Multan and Lahore, laid in the mid 1850s, was supported by Harappan bricks.

In 1861, three years after the dissolution of the East India Company and the establishment of Crown rule in India, archaeology on the subcontinent became more formally organised with the founding of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Alexander Cunningham, the Survey's first director-general, who had visited Harappa in 1853 and had noted the imposing brick walls, visited again to carry out a survey, but this time of a site whose entire upper layer had been stripped in the interim. Although his original goal of demonstrating Harappa to be a lost Buddhist city mentioned in the seventh century CE travels of the Chinese visitor, Xuanzang, proved elusive, Cunningham did publish his findings in 1875. For the first time, he interpreted a Harappan stamp seal, with its unknown script, which he concluded to be of an origin foreign to India.

Archaeological work in Harappa thereafter flagged until a new viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, pushed through the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act 1904, and appointed John Marshall to lead the ASI. Several years later, Hiranand Sastri, who had been assigned by Marshall to survey Harappa, reported it to be of non-Buddhist origin, and by implication more ancient. Expropriating Harappa for the ASI under the Act, Marshall directed ASI archaeologist Daya Ram Sahni to excavate the site's two mounds.

Farther south, along the main stem of the Indus in Sind province, the largely undisturbed site of Mohenjo-daro had attracted notice. Marshall deputed a succession of ASI officers to survey the site. These included D. R. Bhandarkar (1911), R. D. Banerji (1919, 1922–1923), and M.S. Vats (1924). In 1923, on his second visit to Mohenjo-daro, Baneriji wrote to Marshall about the site, postulating an origin in "remote antiquity," and noting a congruence of some of its artifacts with those of Harappa. Later in 1923, Vats, also in correspondence with Marshall, noted the same more specifically about the seals and the script found at both sites. On the weight of these opinions, Marshall ordered crucial data from the two sites to be brought to one location and invited Banerji and Sahni to a joint discussion. By 1924, Marshall had become convinced of the significance of the finds, and on 24 September 1924, made a tentative but conspicuous public intimation in the Illustrated London News :

"Not often has it been given to archaeologists, as it was given to Schliemann at Tiryns and Mycenae, or to Stein in the deserts of Turkestan, to light upon the remains of a long forgotten civilization. It looks, however, at this moment, as if we were on the threshold of such a discovery in the plains of the Indus."

Systematic excavations began in Mohenjo-daro in 1924–25 with that of K. N. Dikshit, continuing with those of H. Hargreaves (1925–1926), and Ernest J. H. Mackay (1927–1931). By 1931, much of Mohenjo-daro had been excavated, but occasional excavations continued, such as the one led by Mortimer Wheeler, a new director-general of the ASI appointed in 1944.

After the partition of India in 1947, when most excavated sites of the Indus Valley civilisation lay in territory awarded to Pakistan, the Archaeological Survey of India, its area of authority reduced, carried out large numbers of surveys and excavations along the Ghaggar-Hakra system in India. Some speculated that the Ghaggar-Hakra system might yield more sites than the Indus river basin. By 2002, over 1,000 Mature Harappan cities and settlements had been reported, of which just under a hundred had been excavated, mainly in the general region of the Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra rivers and their tributaries; however, there are only five major urban sites: Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, Ganeriwala and Rakhigarhi. According to a historian approximately 616 sites have been reported in India, whereas 406 sites have been reported in Pakistan. However, according to an archaeologist, many Ghaggar-Hakra sites in India are those of local cultures; some sites display contact with Harappan civilization, but only a few are fully developed Harappan ones.

Unlike India, in which after 1947, the ASI attempted to "Indianise" archaeological work in keeping with the new nation's goals of national unity and historical continuity, in Pakistan the national imperative was the promotion of Islamic heritage, and consequently archaeological work on early sites was left to foreign archaeologists. After the partition, Mortimer Wheeler, the Director of ASI from 1944, oversaw the establishment of archaeological institutions in Pakistan, later joining a UNESCO effort tasked to conserve the site at Mohenjo-daro. Other international efforts at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa have included the German Aachen Research Project Mohenjo-daro, the Italian Mission to Mohenjo-daro, and the US Harappa Archaeological Research Project (HARP) founded by George F. Dales. Following a chance flash flood which exposed a portion of an archaeological site at the foot of the Bolan Pass in Balochistan, excavations were carried out in Mehrgarh by French archaeologist Jean-François Jarrige and his team.

Chronology :

The cities of the Indus Valley Civilisation had "social hierarchies, their writing system, their large planned cities and their long-distance trade [which] mark them to archaeologists as a full-fledged 'civilisation.'" The mature phase of the Harappan civilisation lasted from c. 2600–1900 BCE. With the inclusion of the predecessor and successor cultures – Early Harappan and Late Harappan, respectively – the entire Indus Valley Civilisation may be taken to have lasted from the 33rd to the 14th centuries BCE. It is part of the Indus Valley Tradition, which also includes the pre-Harappan occupation of Mehrgarh, the earliest farming site of the Indus Valley.

Several periodisations are employed for the periodisation of the IVC. The most commonly used classifies the Indus Valley Civilisation into Early, Mature and Late Harappan Phase. An alternative approach by Shaffer divides the broader Indus Valley Tradition into four eras, the pre-Harappan "Early Food Producing Era," and the Regionalisation, Integration, and Localisation eras, which correspond roughly with the Early Harappan, Mature Harappan, and Late Harappan phases.

Pre-Harappan

era: Mehrgarh :

Jean-Francois Jarrige argues for an independent origin of Mehrgarh. Jarrige notes "the assumption that farming economy was introduced full-fledged from Near-East to South Asia," and the similarities between Neolithic sites from eastern Mesopotamia and the western Indus valley, which are evidence of a "cultural continuum" between those sites. But given the originality of Mehrgarh, Jarrige concludes that Mehrgarh has an earlier local background," and is not a "'backwater' of the Neolithic culture of the Near East."

Lukacs and Hemphill suggest an initial local development of Mehrgarh, with a continuity in cultural development but a change in population. According to Lukacs and Hemphill, while there is a strong continuity between the neolithic and chalcolithic (Copper Age) cultures of Mehrgarh, dental evidence shows that the chalcolithic population did not descend from the neolithic population of Mehrgarh, which "suggests moderate levels of gene flow." Mascarenhas et al. (2015) note that "new, possibly West Asian, body types are reported from the graves of Mehrgarh beginning in the Togau phase (3800 BCE)."

Gallego Romero et al. (2011) state that their research on lactose tolerance in India suggests that "the west Eurasian genetic contribution identified by Reich et al. (2009) principally reflects gene flow from Iran and the Middle East." They further note that " the earliest evidence of cattle herding in south Asia comes from the Indus River Valley site of Mehrgarh and is dated to 7,000 YBP."

Early Harappan :

Early Harappan Period, c. 3300–2600 BCE

Terracotta boat in the shape of a bull, and female figurines. Kot Diji period (c. 2800-2600 BC) The Early Harappan Ravi Phase, named after the nearby Ravi River, lasted from c.3300 BCE until 2800 BCE. It is related to the Hakra Phase, identified in the Ghaggar-Hakra River Valley to the west, and predates the Kot Diji Phase (2800–2600 BCE, Harappan 2), named after a site in northern Sindh, Pakistan, near Mohenjo-daro. The earliest examples of the Indus script date to the 3rd millennium BCE.

The mature phase of earlier village cultures is represented by Rehman Dheri and Amri in Pakistan. Kot Diji represents the phase leading up to Mature Harappan, with the citadel representing centralised authority and an increasingly urban quality of life. Another town of this stage was found at Kalibangan in India on the Hakra River.

Trade networks linked this culture with related regional cultures and distant sources of raw materials, including lapis lazuli and other materials for bead-making. By this time, villagers had domesticated numerous crops, including peas, sesame seeds, dates, and cotton, as well as animals, including the water buffalo. Early Harappan communities turned to large urban centres by 2600 BCE, from where the mature Harappan phase started. The latest research shows that Indus Valley people migrated from villages to cities.

The final stages of the Early Harappan period are characterised by the building of large walled settlements, the expansion of trade networks, and the increasing integration of regional communities into a "relatively uniform" material culture in terms of pottery styles, ornaments, and stamp seals with Indus script, leading into the transition to the Mature Harappan phase.

Mature Harappan :

Mature Harappan Period, c. 2600–1900 BCE

View of Granary and Great Hall on Mound F in Harappa

Archaeological remains of washroom drainage system at Lothal

Dholavira in Gujarat, India, is one of the largest cities of Indus Valley Civilisation, with stepwell steps to reach the water level in artificially constructed reservoirs.

Skull of a Harappan, Indian Museum According to Giosan et al. (2012), the slow southward migration of the monsoons across Asia initially allowed the Indus Valley villages to develop by taming the floods of the Indus and its tributaries. Flood-supported farming led to large agricultural surpluses, which in turn supported the development of cities. The IVC residents did not develop irrigation capabilities, relying mainly on the seasonal monsoons leading to summer floods. Brooke further notes that the development of advanced cities coincides with a reduction in rainfall, which may have triggered a reorganisation into larger urban centers.

According to J.G. Shaffer and D.A. Lichtenstein, the Mature Harappan Civilisation was "a fusion of the Bagor, Hakra, and Kot Diji traditions or 'ethnic groups' in the Ghaggar-Hakra valley on the borders of India and Pakistan".

By 2600 BCE, the Early Harappan communities turned into large urban centres. Such urban centres include Harappa, Ganeriwala, Mohenjo-daro in modern-day Pakistan, and Dholavira, Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Rupar, and Lothal in modern-day India. In total, more than 1,000 cities and settlements have been found, mainly in the general region of the Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra Rivers and their tributaries.

Cities

:

As seen in Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and the recently partially excavated Rakhigarhi, this urban plan included the world's first known urban sanitation systems: see hydraulic engineering of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Within the city, individual homes or groups of homes obtained water from wells. From a room that appears to have been set aside for bathing, waste water was directed to covered drains, which lined the major streets. Houses opened only to inner courtyards and smaller lanes. The house-building in some villages in the region still resembles in some respects the house-building of the Harappans.

The ancient Indus systems of sewerage and drainage that were developed and used in cities throughout the Indus region were far more advanced than any found in contemporary urban sites in the Middle East and even more efficient than those in many areas of Pakistan and India today. The advanced architecture of the Harappans is shown by their impressive dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick platforms, and protective walls. The massive walls of Indus cities most likely protected the Harappans from floods and may have dissuaded military conflicts.

The purpose of the citadel remains debated. In sharp contrast to this civilisation's contemporaries, Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, no large monumental structures were built. There is no conclusive evidence of palaces or temples – or of kings, armies, or priests. Some structures are thought to have been granaries. Found at one city is an enormous well-built bath (the "Great Bath"), which may have been a public bath. Although the citadels were walled, it is far from clear that these structures were defensive.

Most city dwellers appear to have been traders or artisans, who lived with others pursuing the same occupation in well-defined neighbourhoods. Materials from distant regions were used in the cities for constructing seals, beads and other objects. Among the artefacts discovered were beautiful glazed faïence beads. Steatite seals have images of animals, people (perhaps gods), and other types of inscriptions, including the yet un-deciphered writing system of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Some of the seals were used to stamp clay on trade goods.

Although some houses were larger than others, Indus Civilisation cities were remarkable for their apparent, if relative, egalitarianism. All the houses had access to water and drainage facilities. This gives the impression of a society with relatively low wealth concentration, though clear social levelling is seen in personal adornments.[clarification needed]

Authority and governance :

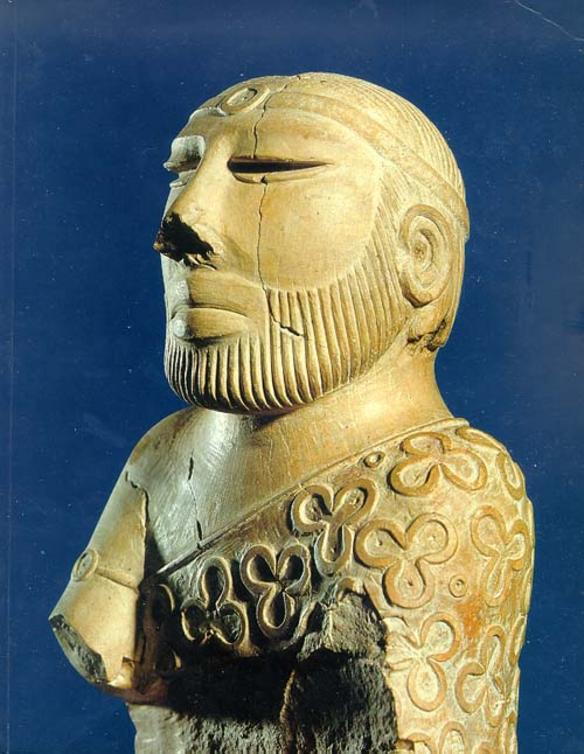

So-called "Priest King" statue, Mohenjo-daro, late Mature Harappan period, National Museum, Karachi, Pakistan Archaeological records provide no immediate answers for a centre of power or for depictions of people in power in Harappan society. But, there are indications of complex decisions being taken and implemented. For instance, the majority of the cities were constructed in a highly uniform and well-planned grid pattern, suggesting they were planned by a central authority; extraordinary uniformity of Harappan artefacts as evident in pottery, seals, weights and bricks; presence of public facilities and monumental architecture; heterogeneity in the mortuary symbolism and in grave goods (items included in burials).[citation needed]

These are the major theories : [citation needed]

•

There was a single state, given the similarity in artefacts, the

evidence for planned settlements, the standardised ratio of brick

size, and the establishment of settlements near sources of raw material.

Harappan weights found in the Indus Valley These chert weights were in a ratio of 5:2:1 with weights of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 units, with each unit weighing approximately 28 grams, similar to the English Imperial ounce or Greek uncia, and smaller objects were weighed in similar ratios with the units of 0.871. However, as in other cultures, actual weights were not uniform throughout the area. The weights and measures later used in Kautilya's Arthashastra (4th century BCE) are the same as those used in Lothal.

Harappans evolved some new techniques in metallurgy and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin.[citation needed]

A touchstone bearing gold streaks was found in Banawali, which was probably used for testing the purity of gold (such a technique is still used in some parts of India).

Arts and crafts :

Fragment of a large deep vessel; circa 2500 BC; red pottery with

red and black slip-painted decoration; 12.5 × 15.5 cm (4 15/16

× 6 1/8 in.); Brooklyn Museum (New York City).

A number of gold, terracotta and stone figurines of girls in dancing poses reveal the presence of some dance form. These terracotta figurines included cows, bears, monkeys, and dogs. The animal depicted on a majority of seals at sites of the mature period has not been clearly identified. Part bull, part zebra, with a majestic horn, it has been a source of speculation. As yet, there is insufficient evidence to substantiate claims that the image had religious or cultic significance, but the prevalence of the image raises the question of whether or not the animals in images of the IVC are religious symbols.

Many crafts including, "shell working, ceramics, and agate and glazed steatite bead making" were practised and the pieces were used in the making of necklaces, bangles, and other ornaments from all phases of Harappan culture. Some of these crafts are still practised in the subcontinent today. Some make-up and toiletry items (a special kind of combs (kakai), the use of collyrium and a special three-in-one toiletry gadget) that were found in Harappan contexts still have similar counterparts in modern India. Terracotta female figurines were found (c. 2800–2600 BCE) which had red colour applied to the "manga" (line of partition of the hair).

Human statuettes :

The Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro; 2300-1750 BCE; bronze; height: 10.8 cm (4 1/4 in.) A handful of realistic statuettes have been found at IVC sites, of which much the most famous is the lost-wax casting bronze statuette of a slender-limbed Dancing Girl adorned with bangles, found in Mohenjo-daro. Two other realistic statuettes have been found in Harappa in proper stratified excavations, which display near-Classical treatment of the human shape: the statuette of a dancer who seems to be male, and a red jasper male torso, both now in the Delhi National Museum. Sir John Marshall reacted with surprise when he saw these two statuettes from Harappa :

When I first saw them I found it difficult to believe that they were prehistoric; they seemed to completely upset all established ideas about early art, and culture. Modeling such as this was unknown in the ancient world up to the Hellenistic age of Greece, and I thought, therefore, that some mistake must surely have been made; that these figures had found their way into levels some 3000 years older than those to which they properly belonged ... Now, in these statuettes, it is just this anatomical truth which is so startling; that makes us wonder whether, in this all-important matter, Greek artistry could possibly have been anticipated by the sculptors of a far-off age on the banks of the Indus.

These statuettes remain controversial, due to their advanced techniques. Regarding the red jasper torso, the discoverer, Vats, claims a Harappan date, but Marshall considered this statuette is probably historical, dating to the Gupta period, comparing it to the much later Lohanipur torso. A second rather similar grey stone statuette of a dancing male was also found about 150 meters away in a secure Mature Harappan stratum. Overall, anthropologist Gregory Possehl tends to consider that these statuettes probably form the pinnacle of Indus art during the Mature Harappan period.

Seals :

Stamp seals, some of them with Indus script; probably made of steatite; British Museum (London) Thousands of steatite seals have been recovered, and their physical character is fairly consistent. In size they range from squares of side 2 to 4 cm (3/4 to 1 1/2 in). In most cases they have a pierced boss at the back to accommodate a cord for handling or for use as personal adornment.

Seals have been found at Mohenjo-daro depicting a figure standing on its head, and another, on the Pashupati seal, sitting cross-legged in what some [who?] call a yoga-like pose (see image, the so-called Pashupati, below). This figure has been variously identified. Sir John Marshall identified a resemblance to the Hindu god, Shiv.

A harp-like instrument depicted on an Indus seal and two shell objects found at Lothal indicate the use of stringed musical instruments.

A human deity with the horns, hooves and tail of a bull also appears in the seals, in particular in a fighting scene with a horned tiger-like beast. This deity has been compared to the Mesopotamian bull-man Enkidu. Several seals also show a man fighting two lions or tigers, a "Master of Animals" motif common to civilizations in Western and South Asia.

Trade

and transportation :

Harappan burnished and painted clay ovoid Vase, with round carnelian beads. (3rd Millennium-2nd Millennium BCE) During 4300–3200 BCE of the chalcolithic period (copper age), the Indus Valley Civilisation area shows ceramic similarities with southern Turkmenistan and northern Iran which suggest considerable mobility and trade. During the Early Harappan period (about 3200–2600 BCE), similarities in pottery, seals, figurines, ornaments, etc. document intensive caravan trade with Central Asia and the Iranian plateau.

Archaeological discoveries suggest that trade routes between Mesopotamia and the Indus were active during the 3rd millennium BCE, leading to the development of Indus-Mesopotamia relations.

Boat with direction finding birds to find land. Model of Mohenjo-daro seal, 2500-1750 BCE Judging from the dispersal of Indus civilisation artefacts, the trade networks economically integrated a huge area, including portions of Afghanistan, the coastal regions of Persia, northern and western India, and Mesopotamia, leading to the development of Indus-Mesopotamia relations. Studies of tooth enamel from individuals buried at Harappa suggest that some residents had migrated to the city from beyond the Indus Valley. There is some evidence that trade contacts extended to Crete and possibly to Egypt.

There was an extensive maritime trade network operating between the Harappan and Mesopotamian civilisations as early as the middle Harappan Phase, with much commerce being handled by "middlemen merchants from Dilmun" (modern Bahrain and Failaka located in the Persian Gulf). Such long-distance sea trade became feasible with the development of plank-built watercraft, equipped with a single central mast supporting a sail of woven rushes or cloth.

It is generally assumed that most trade between the Indus Valley (ancient Meluhha) and western neighbors proceeded up the Persian Gulf rather than overland. Although there is no incontrovertible proof that this was indeed the case, the distribution of Indus-type artifacts on the Oman peninsula, on Bahrain and in southern Mesopotamia makes it plausible that a series of maritime stages linked the Indus Valley and the Gulf region.

In the 1980s, important archaeological discoveries were made at Ras al-Jinz (Oman), demonstrating maritime Indus Valley connections with the Arabian Peninsula.

Agriculture

:

According to Jean-Francois Jarrige, farming had an independent origin at Mehrgarh, despite the similarities which he notes between Neolithic sites from eastern Mesopotamia and the western Indus valley, which are evidence of a "cultural continuum" between those sites. Nevertheless, Jarrige concludes that Mehrgarh has an earlier local background," and is not a "'backwater' of the Neolithic culture of the Near East." Archaeologist Jim G. Shaffer writes that the Mehrgarh site "demonstrates that food production was an indigenous South Asian phenomenon" and that the data support interpretation of "the prehistoric urbanisation and complex social organisation in South Asia as based on indigenous, but not isolated, cultural developments".

Jarrige notes that the people of Mehrgarh used domesticated wheats and barley, while Shaffer and Liechtenstein note that the major cultivated cereal crop was naked six-row barley, a crop derived from two-row barley. Gangal agrees that "Neolithic domesticated crops in Mehrgarh include more than 90% barley," noting that "there is good evidence for the local domestication of barley." Yet, Gangal also notes that the crop also included "a small amount of wheat," which "are suggested to be of Near-Eastern origin, as the modern distribution of wild varieties of wheat is limited to Northern Levant and Southern Turkey."

The cattle that are often portrayed on Indus seals are humped Indian aurochs, which are similar to Zebu cattle. Zebu cattle is still common in India, and in Africa. It is different from the European cattle, and had been originally domesticated on the Indian subcontinent, probably in the Baluchistan region of Pakistan.

Research by J. Bates et al. (2016) confirms that Indus populations were the earliest people to use complex multi-cropping strategies across both seasons, growing foods during summer (rice, millets and beans) and winter (wheat, barley and pulses), which required different watering regimes. Bates et al. (2016) also found evidence for an entirely separate domestication process of rice in ancient South Asia, based around the wild species Oryza nivara. This led to the local development of a mix of "wetland" and "dryland" agriculture of local Oryza sativa indica rice agriculture, before the truly "wetland" rice Oryza sativa japonica arrived around 2000 BCE.

Language

:

According to Heggarty and Renfrew, Dravidian languages may have spread into the Indian subcontinent with the spread of farming. According to David McAlpin, the Dravidian languages were brought to India by immigration into India from Elam. In earlier publications, Renfrew also stated that proto-Dravidian was brought to India by farmers from the Iranian part of the Fertile Crescent, but more recently Heggarty and Renfrew note that "a great deal remains to be done in elucidating the prehistory of Dravidian." They also note that "McAlpin's analysis of the language data, and thus his claims, remain far from orthodoxy." Heggarty and Renfrew conclude that several scenarios are compatible with the data, and that "the linguistic jury is still very much out."

Possible writing system :

Ten Indus characters from the northern gate of Dholavira, dubbed the Dholavira Signboard, one of the longest known sequences of Indus characters Between 400 and as many as 600 distinct Indus symbols have been found on seals, small tablets, ceramic pots and more than a dozen other materials, including a "signboard" that apparently once hung over the gate of the inner citadel of the Indus city of Dholavira. Typical Indus inscriptions are no more than four or five characters in length, most of which (aside from the Dholavira "signboard") are tiny; the longest on a single surface, which is less than 2.5 cm (1 in) square, is 17 signs long; the longest on any object (found on three different faces of a mass-produced object) has a length of 26 symbols.

While the Indus Valley Civilisation is generally characterised as a literate society on the evidence of these inscriptions, this description has been challenged by Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel (2004) who argue that the Indus system did not encode language, but was instead similar to a variety of non-linguistic sign systems used extensively in the Near East and other societies, to symbolise families, clans, gods, and religious concepts. Others have claimed on occasion that the symbols were exclusively used for economic transactions, but this claim leaves unexplained the appearance of Indus symbols on many ritual objects, many of which were mass-produced in moulds. No parallels to these mass-produced inscriptions are known in any other early ancient civilisations.

In a 2009 study by P.N. Rao et al. published in Science, computer scientists, comparing the pattern of symbols to various linguistic scripts and non-linguistic systems, including DNA and a computer programming language, found that the Indus script's pattern is closer to that of spoken words, supporting the hypothesis that it codes for an as-yet-unknown language.

Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel have disputed this finding, pointing out that Rao et al. did not actually compare the Indus signs with "real-world non-linguistic systems" but rather with "two wholly artificial systems invented by the authors, one consisting of 200,000 randomly ordered signs and another of 200,000 fully ordered signs, that they spuriously claim represent the structures of all real-world non-linguistic sign systems". Farmer et al. have also demonstrated that a comparison of a non-linguistic system like medieval heraldic signs with natural languages yields results similar to those that Rao et al. obtained with Indus signs. They conclude that the method used by Rao et al. cannot distinguish linguistic systems from non-linguistic ones.

The messages on the seals have proved to be too short to be decoded by a computer. Each seal has a distinctive combination of symbols and there are too few examples of each sequence to provide a sufficient context. The symbols that accompany the images vary from seal to seal, making it impossible to derive a meaning for the symbols from the images. There have, nonetheless, been a number of interpretations offered for the meaning of the seals. These interpretations have been marked by ambiguity and subjectivity.

Photos of many of the thousands of extant inscriptions are published in the Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions (1987, 1991, 2010), edited by Asko Parpola and his colleagues. The most recent volume republished photos taken in the 1920s and 1930s of hundreds of lost or stolen inscriptions, along with many discovered in the last few decades; formerly, researchers had to supplement the materials in the Corpus by study of the tiny photos in the excavation reports of Marshall (1931), MacKay (1938, 1943), Wheeler (1947), or reproductions in more recent scattered sources.

Edakkal Caves in Wayanad district of Kerala contain drawings that range over periods from as early as 5000 BCE to 1000 BCE. The youngest group of paintings have been in the news for a possible connection to the Indus Valley Civilisation.

Religion :

The Pashupati seal, showing a seated figure, surrounded by animals The religion and belief system of the Indus Valley people have received considerable attention, especially from the view of identifying precursors to deities and religious practices of Indian religions that later developed in the area. However, due to the sparsity of evidence, which is open to varying interpretations, and the fact that the Indus script remains undeciphered, the conclusions are partly speculative and largely based on a retrospective view from a much later Hindu perspective.

An early and influential work in the area that set the trend for Hindu interpretations of archaeological evidence from the Harappan sites was that of John Marshall, who in 1931 identified the following as prominent features of the Indus religion: a Great Male God and a Mother Goddess; deification or veneration of animals and plants; symbolic representation of the phallus (linga) and vulva (yoni); and, use of baths and water in religious practice. Marshall's interpretations have been much debated, and sometimes disputed over the following decades.

Swastik seals of Indus Valley Civilisation in British Museum One Indus Valley seal shows a seated figure with a horned headdress, possibly tricephalic and possibly ithyphallic, surrounded by animals. Marshall identified the figure as an early form of the Hindu god Shiv (or Rudra), who is associated with asceticism, yog, and ling; regarded as a lord of animals; and often depicted as having three eyes. The seal has hence come to be known as the Pashupati Seal, after Pashupati (lord of all animals), an epithet of Shiv. While Marshall's work has earned some support, many critics and even supporters have raised several objections. Doris Srinivasan has argued that the figure does not have three faces, or yogic posture, and that in Vedic literature Rudra was not a protector of wild animals. Herbert Sullivan and Alf Hiltebeitel also rejected Marshall's conclusions, with the former claiming that the figure was female, while the latter associated the figure with Mahish, the Buffalo God and the surrounding animals with vahan's (vehicles) of deities for the four cardinal directions. Writing in 2002, Gregory L. Possehl concluded that while it would be appropriate to recognise the figure as a deity, its association with the water buffalo, and its posture as one of ritual discipline, regarding it as a proto-Shiv would be going too far. Despite the criticisms of Marshall's association of the seal with a proto-Shiv icon, it has been interpreted as the Tirthankar Rishabhanath by Jains and Vilas Sangave. Historians such as Heinrich Zimmer and Thomas McEvilley believe that there is a connection between first Jain Tirthankar Rishabhanath and the Indus Valley civilisation.

Marshall hypothesised the existence of a cult of Mother Goddess worship based upon excavation of several female figurines, and thought that this was a precursor of the Hindu sect of Shaktism. However the function of the female figurines in the life of Indus Valley people remains unclear, and Possehl does not regard the evidence for Marshall's hypothesis to be "terribly robust". Some of the baetyls interpreted by Marshall to be sacred phallic representations are now thought to have been used as pestles or game counters instead, while the ring stones that were thought to symbolise yoni were determined to be architectural features used to stand pillars, although the possibility of their religious symbolism cannot be eliminated. Many Indus Valley seals show animals, with some depicting them being carried in processions, while others show chimeric creations. One seal from Mohenjo-daro shows a half-human, half-buffalo monster attacking a tiger, which may be a reference to the Sumerian myth of such a monster created by goddess Aruru to fight Gilgamesh. (in India there is a story mentioned in Purans about a Asur called Mahishasur who was half human and half buffalo and was killed by Goddess Durga).

In contrast to contemporary Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilisations, Indus Valley lacks any monumental palaces, even though excavated cities indicate that the society possessed the requisite engineering knowledge. This may suggest that religious ceremonies, if any, may have been largely confined to individual homes, small temples, or the open air. Several sites have been proposed by Marshall and later scholars as possibly devoted to religious purpose, but at present only the Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro is widely thought to have been so used, as a place for ritual purification. The funerary practices of the Harappan civilisation are marked by fractional burial (in which the body is reduced to skeletal remains by exposure to the elements before final interment), and even cremation.

Late Harappan :

Late Harappan Period, c. 1900–1300 BCE

Late Harappan figures from a hoard at Daimabad, 2000 BCE Around 1900 BCE signs of a gradual decline began to emerge, and by around 1700 BCE most of the cities had been abandoned. Recent examination of human skeletons from the site of Harappa has demonstrated that the end of the Indus civilisation saw an increase in inter-personal violence and in infectious diseases like leprosy and tuberculosis.

According to historian Upinder Singh, "the general picture presented by the late Harappan phase is one of a breakdown of urban networks and an expansion of rural ones."

During the period of approximately 1900 to 1700 BCE, multiple regional cultures emerged within the area of the Indus civilisation. The Cemetery H culture was in Punjab, Haryana, and Western Uttar Pradesh, the Jhukar culture was in Sindh, and the Rangpur culture (characterised by Lustrous Red Ware pottery) was in Gujarat. Other sites associated with the Late phase of the Harappan culture are Pirak in Balochistan, Pakistan, and Daimabad in Maharashtra, India.

The largest Late Harappan sites are Kudwala in Cholistan, Bet Dwarka in Gujarat, and Daimabad in Maharashtra, which can be considered as urban, but they are smaller and few in number compared with the Mature Harappan cities. Bet Dwarka was fortified and continued to have contacts with the Persian Gulf region, but there was a general decrease of long-distance trade. On the other hand, the period also saw a diversification of the agricultural base, with a diversity of crops and the advent of double-cropping, as well as a shift of rural settlement towards the east and the south.

The pottery of the Late Harappan period is described as "showing some continuity with mature Harappan pottery traditions," but also distinctive differences. Many sites continued to be occupied for some centuries, although their urban features declined and disappeared. Formerly typical artifacts such as stone weights and female figurines became rare. There are some circular stamp seals with geometric designs, but lacking the Indus script which characterised the mature phase of the civilisation. Script is rare and confined to potsherd inscriptions. There was also a decline in long-distance trade, although the local cultures show new innovations in faience and glass making, and carving of stone beads. Urban amenities such as drains and the public bath were no longer maintained, and newer buildings were "poorly constructed". Stone sculptures were deliberately vandalised, valuables were sometimes concealed in hoards, suggesting unrest, and the corpses of animals and even humans were left unburied in the streets and in abandoned buildings.

During the later half of the 2nd millennium BCE, most of the post-urban Late Harappan settlements were abandoned altogether. Subsequent material culture was typically characterised by temporary occupation, "the campsites of a population which was nomadic and mainly pastoralist" and which used "crude handmade pottery." However, there is greater continuity and overlap between Late Harappan and subsequent cultural phases at sites in Punjab, Haryana, and western Uttar Pradesh, primarily small rural settlements.

Aryan :

Painted pottery urns from Harappa (Cemetery H culture, c. 1900-1300 BCE) In 1953 Sir Mortimer Wheeler proposed that the invasion of an Indo-European tribe from Central Asia, the "Aryans", caused the decline of the Indus Civilisation. As evidence, he cited a group of 37 skeletons found in various parts of Mohenjo-daro, and passages in the Vedas referring to battles and forts. However, scholars soon started to reject Wheeler's theory, since the skeletons belonged to a period after the city's abandonment and none were found near the citadel. Subsequent examinations of the skeletons by Kenneth Kennedy in 1994 showed that the marks on the skulls were caused by erosion, and not by violence.

In the Cemetery H culture (the late Harappan phase in the Punjab region), some of the designs painted on the funerary urns have been interpreted through the lens of Vedic literature : for instance, peacocks with hollow bodies and a small human form inside, which has been interpreted as the souls of the dead, and a hound that can be seen as the hound of Yam, the god of death. This may indicate the introduction of new religious beliefs during this period, but the archaeological evidence does not support the hypothesis that the Cemetery H people were the destroyers of the Harappan cities.

Climate

change and drought :

The Ghaggar-Hakra system was rain-fed, and water-supply depended on the monsoons. The Indus Valley climate grew significantly cooler and drier from about 1800 BCE, linked to a general weakening of the monsoon at that time. The Indian monsoon declined and aridity increased, with the Ghaggar-Hakra retracting its reach towards the foothills of the Himalaya, leading to erratic and less extensive floods that made inundation agriculture less sustainable.

Aridification reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation's demise, and to scatter its population eastward. According to Giosan et al. (2012), the IVC residents did not develop irrigation capabilities, relying mainly on the seasonal monsoons leading to summer floods. As the monsoons kept shifting south, the floods grew too erratic for sustainable agricultural activities. The residents then migrated towards the Ganges basin in the east, where they established smaller villages and isolated farms. The small surplus produced in these small communities did not allow development of trade, and the cities died out.

Earthquakes

:

Continuity

:

At sites such as Bhagwanpura (in Haryana), archaeological excavations have discovered an overlap between the final phase of Late Harappan pottery and the earliest phase of Painted Grey Ware pottery, the latter being associated with the Vedic Culture and dating from around 1200 BCE. This site provides evidence of multiple social groups occupying the same village but using different pottery and living in different types of houses: "over time the Late Harappan pottery was gradually replaced by Painted Grey ware pottery," and other cultural changes indicated by archaeology include the introduction of the horse, iron tools, and new religious practices.

There is also a Harappan site called Rojdi in Rajkot district of Saurashtra. Its excavation started under an archaeological team from Gujarat State Department of Archaeology and the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania in 1982–83. In their report on archaeological excavations at Rojdi, Gregory Possehl and M.H. Raval write that although there are "obvious signs of cultural continuity" between the Harappan Civilisation and later South Asian cultures, many aspects of the Harappan "sociocultural system" and "integrated civilization" were "lost forever," while the Second Urbanisation of India (beginning with the Northern Black Polished Ware culture, c. 600 BCE) "lies well outside this sociocultural environment".

Post-Harappan

:

As of 2016, archaeological data suggests that the material culture classified as Late Harappan may have persisted until at least c. 1000–900 BCE and was partially contemporaneous with the Painted Grey Ware culture. Harvard archaeologist Richard Meadow points to the late Harappan settlement of Pirak, which thrived continuously from 1800 BCE to the time of the invasion of Alexander the Great in 325 BCE.

In the aftermath of the Indus Civilisation's localisation, regional cultures emerged, to varying degrees showing the influence of the Indus Civilisation. In the formerly great city of Harappa, burials have been found that correspond to a regional culture called the Cemetery H culture. At the same time, the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture expanded from Rajasthan into the Gangetic Plain. The Cemetery H culture has the earliest evidence for cremation; a practice dominant in Hinduism today.

Historical

context :

Impression of a cylinder seal of the Akkadian Empire, with label:

"The Divine Sharkalisharri Prince of Akkad, Ibni-Sharrum the

Scribe his servant". The long-horned buffalo is thought to

have come from the Indus Valley, and testifies to exchanges with

Meluhha, the Indus Valley civilization. Circa 2217-2193 BCE. Louvre

Museum.

The IVC has been compared in particular with the civilisations of Elam (also in the context of the Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis) and with Minoan Crete (because of isolated cultural parallels such as the ubiquitous goddess worship and depictions of bull-leaping). The IVC has been tentatively identified with the toponym Meluhha known from Sumerian records; the Sumerians called them Meluhhaites.

Shahr-i-Sokhta, located in southeastern Iran shows trade route with Mesopotamia. A number of seals with Indus script have been also found in Mesopotamian sites.

Dasyu

:

Munda

:

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org/ |

.png)

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png)

.png)

_02.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_Balance_&_Weights.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)