| KING VIKRAMADITYA HISTORY Vikramaditya was a legendary emperor of ancient India. Often characterized as an ideal king, he is known for his generosity, courage, and patronage of scholars. Vikramaditya is featured in hundreds of traditional Indian legends, including those in Baital Pachisi and Singhasan Battisi. Many describe him as a universal ruler, with his capital at Ujjain (Pataliputra or Pratishthan in a few stories).

According to popular tradition, Vikramaditya began the Vikram Samvat era in 57 BCE after defeating the Shakas, and those who believe that he is based on a historical figure place him around the first century BCE. However, this era is identified as "Vikram Samvat" after the ninth century CE. Other scholars believe that Vikramaditya is a mythical character, since several legends about him are fantastic in nature.

"Vikramaditya" was a common title adopted by several Indian kings, and the Vikramaditya legends may be embellished accounts of different kings (particularly Chandragupt II).

Etymology

and names :

Early

legends :

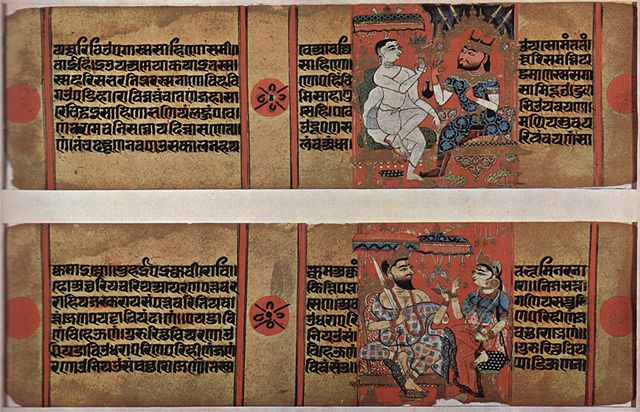

Gah Sattasai (or Gatha-Saptasati), a collection of poems attributed to the Satavahan king Hal (r. 20 – 24 CE), mentions a king named Vikramaditya who gave away his wealth out of charity. However, many stanzas in this work are not common to its revisions and are apparent Gupta-period expansions. The verse about Vikramaditya is similar to a phrase—Anekago-shatasahasra-hiranya-kotipradasya—found in Gupta inscriptions about Samudragupt and Chandragupt II (for example, the Pune and Riddhapur copper-plate inscriptions of Chandragupt's daughter, Prabhavatigupt); this phrase may have been a later, Gupta-era insertion in the work attributed to Hal.

The earliest uncontested mentions of Vikramaditya appear in sixth-century works: the biography of Vasubandhu by Paramarth (499–569) and Vasvadatt by Subandhu. Paramarath quotes a legend which mentions Ayodhya ("A-yu-ja") as the capital of king Vikramaditya ("Pi-ka-la-ma-a-chi-ta"). According to this legend, the king gave 300,000 gold coins to the Samkhya scholar Vindhyavas for defeating Vasubandhu's Buddhist teacher (Buddhamitra) in a philosophical debate. Vasubandhu then wrote Parmarth Saptati, illustrating deficiencies in Samkhya philosophy. Vikramaditya, pleased with Vasubandhu's arguments, gave him 300,000 gold coins as well. Vasubandhu later taught Buddhism to Prince Baladitya and converted the queen to Buddhism after the king's death. According to Subandhu, Vikramaditya was a glorious memory by his time.

In his Si-yu-ki, Xuanzang (c.?602 – c.?664) identifies Vikramaditya as the king of Shravasti. According to his account, the king (despite his treasurer's objections) ordered that 500,000 gold coins be distributed to the poor and gave a man 100,000 gold coins for putting him back on track during a wild boar hunt. Around the same time, a Buddhist monk known as Manorath paid a barber 100,000 gold coins for shaving his head. Vikramaditya, who prided himself on his generosity, was embarrassed and arranged a debate between Manorath and 100 non-Buddhist scholars. After Manorath defeated 99 of the scholars, the king and other non-Buddhists shouted him down and humiliated him at the beginning of the last debate. Before his death, Manorath wrote to his disciple Vasubandhu about the futility of debating biased, ignorant people. Shortly after Vikramaditya's death, Vasubandhu asked his successor, Baladitya, to organise another debate to avenge his mentor's humiliation. In this debate, Vasubandhu defeated 100 non-Buddhist scholars.

Association

with Vikrama Samvat :

A Shak ruler invaded north-western India and oppressed the Hindus. According to one source, he was a Shudra from the Almansura city; according to another, he was a non-Hindu who came from the west. In 78 CE, the Hindu king Vikramaditya defeated him and killed him in the Karur region, located between Multan and the castle of Loni. The astronomers and other people started using this date as the beginning of a new era.

Since there was a difference of over 130 years between the Vikramaditya era and the Shak era, Al-Biruni concluded that their founders were two kings with the same name. The Vikramaditya era named after the first, and the Shak era was associated with the defeat of the Shak ruler by the second Vikramaditya.

According to several later legends—particularly Jain legends—Vikramaditya established the 57 BCE era after he defeated the Shaks and was defeated in turn by Shalivahan, who established the 78 CE era. Both legends are historically inaccurate. There is a difference of 135 years between the beginning of the two eras, and Vikramaditya and Shalivahan could not have lived simultaneously. The association of the era beginning in 57 BCE with Vikramaditya is not found in any source before the ninth century. Earlier sources call this era by several names, including "Krta", "the era of the Malava tribe", or "Samvat" ("Era"). Scholars such as D. C. Sircar and D. R. Bhandarkar believe that the name of the era changed to Vikram Samvat during the reign of Chandragupt II, who had adopted the title of "Vikramaditya". Alternative theories also exist, and Rudolf Hoernlé believed that it was Yashodharman who renamed the era Vikram Samvat. The earliest mention of the Shak era as the Shalivahan era occurs in the 13th century, and may have been an attempt to remove the era's foreign association.

10th-

to 12th-century legends :

The first legend mentions Vikramaditya's rivalry with the king of Pratishthan. In this version, that king is named Narasimha (not Shalivahan) and Vikramaditya's capital is Pataliputra (not Ujjain). According to the legend, Vikramaditya was an adversary of Narasimha who invaded Dakshinpath and besieged Pratishthan; he was defeated and forced to retreat. He then entered Pratishthan in disguise and won over a courtesan. Vikramaditya was her lover for some time before secretly returning to Pataliputra. Before his return, he left five golden statues which he had received from Kuber at the courtesan's house. If a limb of one of these miraculous statues was broken off and gifted to someone, the golden limb would grow back. Mourning the loss of her lover, the courtesan turned to charity; known for her gifts of gold, she soon surpassed Narasimha in fame. Vikramaditya later returned to the courtesan's house, where Narasimha met and befriended him. Vikramaditya married the courtesan and brought her to Pataliputra.

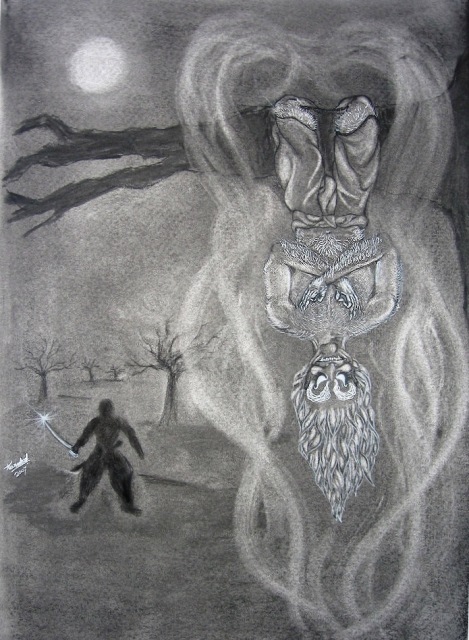

A ghostly being hangs upside-down from a tree limb, with a man with a sword in the background Book 12 (Shashankavati) contains the vetal panchavimshati legends, popularly known as Baital Pachisi. It is a collection of 25 stories in which the king tries to capture and hold a vetal who tells a puzzling tale which ends with a question. In addition to Kathasaritsagar, the collection appears in three other Sanskrit recensions, a number of Indian vernacular versions and several English translations from Sanskrit and Hindi; it is the most popular of the Vikramaditya legends. There are minor variations among the recensions; see List of Vetal Tales. In Kshemendra, Somdev and Shivdas's recensions, the king is named Trivikramasen; in Kathasaritsagar, his capital is located at Pratishthan. At the end of the story, the reader learns that he was formerly Vikramaditya. Later texts, such as the Sanskrit Vetal-Vikramaditya-Katha and the modern vernacular versions, identify the king as Vikramaditya of Ujjain.

Book 18 (Vishamshila) contains another legend told by Naravahandatt to an assembly of hermits in the ashram of a sage, Kashyap. According to the legend, Indra and other dev's told Shiv that the slain asur's were reborn as malechs. Shiv then ordered his attendant, Malyavat, to be born in Ujjain as the prince of the Avanti kingdom and kill the malechs. The deity appeared to the Avanti king Mahendraditya in a dream, telling him that a son would be born to his queen Saumyadarshan. He asked the king to name the child Vikramaditya, and told him that the prince would be known as "Vishamshila" because of his hostility to enemies. Malyavat was born as Vikramaditya; when the prince grew up, Mahendraditya retired to Varanasi. Vikramaditya began a campaign to conquer a number of kingdoms and subdued vetals, rakshashs and other demons. His general, Vikramshakti, conquered the Dakshinpath in the south; Madhyadesh in the central region; Surashtra in the west, and the country east of the Ganges; Vikramshakti also made the northern kingdom of Kashmir a tributary state of Vikramaditya. Virsen, the king of Sinhal, gave his daughter Madanalekha to Vikramaditya in marriage. The emperor also married three other women (Gunavati, Chandravati and Madanasundari) and Kalingsena, the princess of Kaling.

The Brihatkathamanjari contains similar legends, with some variations; Vikramaditya's general Vikramshakti defeated a number of malechs, including Kambojs, Yavans, Huns, Barbaras, Tushars and Persians. In Brihatkathamanjari and Kathasaritsagar, Malyavat is later born as Gunadhya (the author of Brihatkath, on which these books are based).

Rajatarangini

:

Parmar

legends :

Simhasan

Dvatrimsik :

The author and date of the original work are unknown. Since the story mentions Bhoj (who died in 1055), it must have been composed after the 11th century. Five primary recensions of the Sanskrit version, Simhasan-dvatrimsik, are dated to the 13th and 14th centuries. According to Sujan Rai's 1695 Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh, its author was Bhoj's Pradhan Mantri (prime minister) Pandit Braj.

Vetal Panchvimshati and Simhasan Dvatrimsik are structurally opposite. In the Vetal tales, Vikramaditya is the central character of the frame story but is unconnected with the individual tales except for hearing them from the vetal. Although the frame story of the Throne Tales is set long after Vikramaditya's death, those tales describe his life and deeds.

Bhavishya

Puran :

According to the Bhavishya Puran, when the world was degraded by non-Vedic faiths, Shiv sent Vikramaditya to earth and established a throne decorated with 32 designs for him (a reference to Simhasan Dvatrimsik). Shiv's wife, Parvati, created a vetal to protect Vikramaditya and instruct him with riddles (a reference to Baital Pachisi legends). After hearing the vetal's stories, Vikramaditya performed an Ashvamegh Yagya. The wandering of the horse defined the boundary of Vikramaditya's empire: the Indus River in the west, Badristhan (Badrinath) in the north, Kapil in the east and Setubandh (Rameshwaram) in the south. The emperor united the four Agnivanshi clans by marrying princesses from the three non-Parmar clans: Vira from the Chauhan clan, Nija from the Chalukya clan, and Bhogavati from the Parihar clan. All the gods except Chandra celebrated his success (a reference to the Chandravanshis, rivals of Suryavanshi clans such as the Parmaras).

There were 18 kingdoms in Vikramaditya's empire of Bharatvarsh (India). After a flawless reign, he ascended to heaven. At the beginning of the Kal Yug, Vikramaditya came from Kailash and convened an assembly of sages from the Naimisha Forest. Gorakhnath, Bhartrhari, Lomharsan, Saunk and other sages recited the Purans and the Uup-puranas. A hundred years after Vikramaditya's death, the Shaks invaded India again. Shalivahan, Vikramaditya's grandson, subjugated them and other invaders. Five hundred years after Shalivahan's death, Bhoj defeated later invaders.

Jain

legends :

•

Prabhachandra's Prabhavak Charit (1127 CE)

Jain tradition originally had four Simhasan-related stories and four vetal-related puzzle stories. Later Jain authors adopted the 32 Simhasan Dvatrimsik and 25 Vetal Panchvimshati stories.

The Jain author Hemchandra names Vikramaditya as one of four learned kings; the other three are Shalivahan, Bhoj and Munj. Merutung's Vicarasreni places his victory at Ujjain in 57 BCE, and hints that his four successors ruled from 3 to 78 CE.

Shalivahan-Vikramaditya rivalry :

Many legends, particularly Jain legends, associate Vikramaditya with Shalivahan of Pratishthan (another legendary king). In some he is defeated by Shalivahan, who begins the Shalivahan era; in others, he is an ancestor of Shalivahan. A few legends call the king of Pratishthan"Vikramaditya". Political rivalry between the kings is sometimes extended to language, with Vikramaditya supporting Sanskrit and Shalivahan supporting Prakrit.

In the Kalkacharya-Kathanak, Vikramaditya's father Gardabhill abducted the sister of Kalka (a Jain acharya). At Kalka's insistence, the Shakas invaded Ujjain and made Gardabhill their prisoner. Vikramaditya later arrived from Pratishthan, defeated the Shakas, and began the Vikram Samvat era to commemorate his victory. According to Alain Daniélou, the Vikramaditya in this legend refers to a Satavahan king.

Other Jain texts contain variations of a legend about Vikramaditya's defeat at the hands of the king of Pratishthan, known as Shatvahan or Shalivahan. This theme is found in Jin-Prabhasuri's Kalp-Pradip, Rajshekhar's Prabandh-Kosh and Salivahan-Charitra, a Marathi work. According to the legend, Shatvahan was the child of the Nag (serpent) chief Shesha and a Brahmin widow who lived in the home of a potter. His name, Shatvahan, was derived from shatani (give) and vahan (a means of transport) because he sculpted elephants, horses and other means of transport with clay and gave them to other children. Vikramaditya perceived omens that his killer had been born. He sent his vetal to find the child; the vetal traced Shatvahan in Pratishthan, and Vikramaditya led an army there. With Nag magic, Shatvahan converted his clay figures of horses, elephants and soldiers into a real army. He defeated Vikramaditya (who fled to Ujjain), began his own era, and became a Jain. There are several variations of this legend: Vikramaditya is killed by Shatvahan's arrow in battle; he marries Shatvahan's daughter and they have a son (known as Vikramasen or Vikram-charitra), or Shatvahan is the son of Manorama, wife of a bodyguard of the king of Pratishthan.

Tamil

legends :

In another Tamil legend, Vikramaditya offers to perform a variant of the navkhandam rite (cutting the body in nine places) to please the gods. He offers to cut his body in eight places (for the eight Bhairavs), and offers his head to the goddess. In return, he convinces the goddess to end human sacrifice.

Chola Purva Patayam (Ancient Chola Record), a Tamil manuscript of uncertain date, contains a legend about the divine origin of the three Tamil dynasties. In this legend, Shalivahan (also known as Bhoj) is a shraman king. He defeats Vikramaditya, and begins persecuting worshipers of Shiv and Vishnu. Shiv then creates the three Tamil kings to defeat him: Vir Cholan, Ula Cheran, and Vajrang Pandiyan. The kings have a number of adventures, including finding treasures and inscriptions of Hindu kings from the age of Shantanu to Vikramaditya. They ultimately defeat Shalivahan in the year 1443 (of an uncertain calendar era, possibly from the beginning of Kal Yug).

Ayodhya

legend :

According to Hans T. Bakker, present-day Ayodhya was originally the Saket mentioned in Buddhist sources. The Gupta emperor Skandgupt, who compared himself to Ram and was also known as Vikramaditya, moved his capital to Saket and renamed it Ayodhya after the legendary city in the Ramayan. The Vikramaditya mentioned in Parmarth's fourth–fifth century CE biography of Vasubandhu is generally identified with a Gupta king, such as Skandgupt or Purugupt. Although the Gupta kings ruled from Pataliputra, Ayodhya was within their domain. However, scholars such as Ashvini Agrawal reject this account as inaccurate.

Other

legends :

Shivdas's 12th– to 14th-century Salivahan Katha (or Shalivahan-Charitra) similarly describes the rivalry between Vikramaditya and Shalivahan. Anand's Madhavnal Kamkandal Katha is a story of separated lovers who are reunited by Vikramaditya. Vikramdaya is a series of verse tales in which the emperor appears as a wise parrot; a similar series is found in the Jain text, Parsvanthcaritra. The 15th-century—or later—Pañcadandachattra Prabandh (The Story of Umbrellas With Five Sticks) contains "stories of magic and witchcraft, full of wonderful adventures, in which Vikramaditya plays the rôle of a powerful magician". Ganapati's 16th-century Gujarati work, Madhavanal-Kamkandal-Katha, also contains Vikramaditya stories.

Navratnas

:

1.

Amarsimha,

Kalidas is the only figure whose association with Vikramaditya is mentioned in works earlier than Jyotirvidbharan. According to Rajsekhar's Kavyamimansa (10th century), Bhoj's Sringar Prakas and Kshemendra's Auchitya-Vichar-Charcha (both 11th century), Vikramaditya sent Kalidas as his ambassador to the Kuntal country (present-day Uttara Kannad). However, the historicity of these reports is doubtful.

Historicity

:

Malav

king :

Critics of this theory say that Gatha Saptashati shows clear signs of Gupta-era interpolation. According to A. K. Warder, Brihatkathamanjari and Kathasaritsagar are "enormously inflated and deformed" recensions of the original Brihatkatha. The early Jain works do not mention Vikramaditya and the navratnas have no historical basis as the nine scholars do not appear to have been contemporary figures. Legends surrounding Vikramaditya are contradictory, border on the fantastic and are inconsistent with historical facts; no epigraphic, numismatic or literary evidence suggests the existence of a king with the name (or title) of Vikramaditya around the first century BCE. Although the Purans contain genealogies of significant Indian kings, they do not mention a Vikramaditya ruling from Ujjain or Pataliputra before the Gupta era. There is little possibility of an historically-unattested, powerful emperor ruling from Ujjain around the first century BCE among the Shungas (187–78 BCE), the Kanvas (75–30), the Shatvahans (230 BCE–220 CE), the Shakas (c. 200 BCE – c. 400 CE) and the Indo-Greeks (180 BCE–10 CE).

Gupta

kings :

Chandragupt II :

Gold coin with Chandragupta II on a horse Some scholars, including D. R. Bhandarkar, V. V. Mirashi and D. C. Sircar, believe that Vikramaditya is probably based on the Gupta king Chandragupt II. Based on coins and the Supi pillar inscription, it is believed that Chandragupt II adopted the title Vikramaditya. The Khambat and Sangli plates of the Rashtrakut king Govind IV use the epithet "Sahsank", which has also been applied to Vikramaditya, for Chandragupt II. According to Alf Hiltebeitel, Chandragupt's victory against the Shakas was transposed to a fictional character who is credited with establishing the Vikram Samvat era.

In most of the legends Vikramaditya had his capital at Ujjain, although some mention him as king of Pataliputra (the Gupta capital). According to D. C. Sircar, Chandragupt II may have defeated the Shaka invaders of Ujjain and made his son, Govindgupt, a viceroy there. Ujjain may have become a second Gupta capital, and legends about him (as Vikramaditya) may have developed. The Guttas of Guttavalal, a minor dynasty based in present-day Karnataka, claimed descent from the Gupta Empire. Their Chauddanpur inscription alludes to Vikramaditya ruling from Ujjain, and several Gutt kings were named Vikramaditya. According to Vasundhara Filliozat, the Gutts confused Vikramaditya with Chandragupt II; however, D. C. Sircar sees this as further proof that Vikramaditya was based on Chandragupt II.

Skandgupt

:

Other

rulers :

Max Müller believed that the Vikramaditya legends were based on the sixth-century Aulikar king Yashodharman. The Aulikars used the Malav era (later known as Vikram Samvat) in their inscriptions. According to Rudolf Hoernlé, the name of the Malav era was changed to Vikramaditya by Yashodharman. Hoernlé also believed that Yashodharman conquered Kashmir and is the Harsh Vikramaditya mentioned in Kalhan's Rajatarangini. Although Yashodharman defeated the Huns (who were led by Mihirkul), the Huns were not the Shakas; Yashodharman's capital was at Daspur (modern Mandsaur), not Ujjain. There is no other evidence that he inspired the Vikramaditya legends.

Legacy

:

The Indian Navy aircraft carrier INS Vikramaditya was christened in honour of Vikramaditya. On 22 December 2016, a commemorative postage stamp honouring Samrat Vikramaditya was released by India Post. Historical-fiction author Shatrujeet Nath retells the emperor's story in his Vikramaditya Veergath series. Currently a series Vikram Betaal Ki Rahasya Gatha is running on &TV where popular actor Aham Sharma is playing the role of Vikramaditya.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org |