| IRANIAN PEOPLE Iranian peoples :

Regions

with significant populations

The Iranian peoples or the Iranic peoples, are a diverse Indo-European ethno-linguistic group.

The Proto-Iranians are believed to have emerged as a separate branch of the Indo-Iranians in Central Asia in the mid-2nd millennium BC. At their peak of expansion in the mid-1st millennium BC, the territory of the Iranian peoples stretched across the entire Eurasian Steppe from the Great Hungarian Plain in the west to the Ordos Plateau in the east, to the Iranian Plateau in the south. The Western Iranian empires of the south came to dominate much of the ancient world from the 6th century BC, leaving an important cultural legacy; and the Eastern Iranians of the steppe played a decisive role in the development of Eurasian nomadism and the Silk Road.

The ancient Iranian peoples who emerged after the 1st millennium BC include the Alans, Bactrians, Dahae, Khwarezmians, Massagetae, Medes, Parthians, Persians, Sagartians, Sakas, Sarmatians, Scythians, Sogdians, and probably Cimmerians, among other Iranian-speaking peoples of Western Asia, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Eastern Steppe.

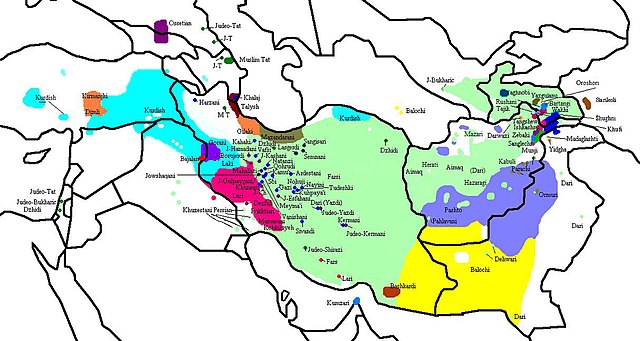

In the 1st millennium AD, their area of settlement, which was mainly concentrated in steppes and deserts of Eurasia, was reduced as a result of Slavic, Germanic, Turkic, and Mongol expansions and many were subjected to Slavicisation and Turkification. Modern Iranian peoples include the Baloch, Gilaks, Kurds, Lurs, Mazanderanis, Ossetians, Pamiris, Pashtuns, Persians, Tajiks, the Talysh, Wakhis, Yaghnobis and Zazas. Their current distribution spreads across the Iranian Plateau, stretching from the Caucasus in the north to the Persian Gulf in the south and from Eastern Turkey in the west to Western Xinjiang in the east—a region that is sometimes called the Iranian Cultural Continent, representing the extent of the Iranian-speakers and the significant influence of the Iranian peoples through the geopolitical reach of Greater Iran.

Name

:

There have been many attempts to qualify the verbal root of ar- in Old Iranian arya-. The following are according to 1957 and later linguists :

•

Emmanuel Laroche (1957): ara- "to fit" ("fitting",

"proper").

The Bistun Inscription of Darius the Great describes itself to have been composed in Arya [language or script] In the Iranian languages, the gentilic is attested as a self-identifier included in ancient inscriptions and the literature of Avesta. The earliest epigraphically attested reference to the word arya- occurs in the Bistun Inscription of the 6th century BC. The inscription of Bistun (or Behistun; Old Persian: Bagastan) describes itself to have been composed in Arya [language or script]. As is also the case for all other Old Iranian language usage, the arya of the inscription does not signify anything but Iranian.

In royal Old Persian inscriptions, the term arya- appears in three different contexts :

•

As the name of the language of the Old Persian version of the inscription

of Darius I in the Bistun Inscription.

The trilingual inscription erected by the command of Shapur I gives a more clear description. The languages used are Parthian, Middle Persian, and Greek. In Greek inscription says "ego ... tou Arianon ethnous despotes eimi", which translates to "I am the king of the kingdom (nation) of the Iranians". In Middle Persian, Shapur says "eranšahr xwaday hem" and in Parthian he says "aryanšahr xwaday ahem".

The Avesta clearly uses airiia- as an ethnic name (Videvdat 1; Yasht 13.143–44, etc.), where it appears in expressions such as airyafi dain´havo ("Iranian lands"), airyo šayanem ("land inhabited by Iranians"), and airyanem vaejo vanhuyafi daityayafi ("Iranian stretch of the good Daitya"). In the late part of the Avesta (Videvdat 1), one of the mentioned homelands was referred to as Airyan'em Vaejah which approximately means "expanse of the Iranians". The homeland varied in its geographic range, the area around Herat (Pliny's view) and even the entire expanse of the Iranian Plateau (Strabo's designation).

The Old Persian and Avestan evidence is confirmed by the Greek sources. Herodotus, in his Histories, remarks about the Iranian Medes that "Medes were called anciently by all people Arians" (7.62). In Armenian sources, the Parthians, Medes and Persians are collectively referred to as Iranians. Eudemus of Rhodes (Dubitationes et Solutiones de Primis Principiis, in Platonis Parmenidem) refers to "the Magi and all those of Iranian (áreion) lineage". Diodorus Siculus (1.94.2) considers Zoroaster (Zathraustes) as one of the Arianoi.

Strabo, in his Geographica (1st century AD), mentions of the Medes, Persians, Bactrians and Sogdians of the Iranian Plateau and Transoxiana of antiquity:

The name of Ariana is further extended to a part of Persia and of Media, as also to the Bactrians and Sogdians on the north; for these speak approximately the same language, with but slight variations.

—

Geographica, 15.8

All this evidence shows that the name Arya was a collective definition, denoting peoples who were aware of belonging to the one ethnic stock, speaking a common language, and having a religious tradition that centered on the cult of Ohrmazd.

The academic usage of the term Iranian is distinct from the state of Iran and its various citizens (who are all Iranian by nationality), in the same way that the term Germanic peoples is distinct from Germans. Some inhabitants of Iran are not necessarily ethnic Iranians by virtue of not being speakers of Iranian languages.

Some scholars such as John Perry prefer the term Iranic as the anthropological name for the linguistic family and ethnic groups of this category (many of which exist outside Iran), while Iranian for anything about the country Iran. He uses the same analogue as in differentiating German from Germanic or differentiating Turkish and Turkic.

History

and settlement :

The Andronovo, BMAC and Yaz cultures have been associated with Indo-Iranians The Proto-Indo-Iranians are commonly identified with the Sintashta culture and the subsequent Andronovo culture within the broader Andronovo horizon, and their homeland with an area of the Eurasian steppe that borders the Ural River on the west, the Tian Shan on the east.

The Indo-Iranians interacted with the Bactria-Magiana Culture, also called "Bactria-Magiana Archaeological Complex". Proto-Indo-Iranian arose due to this influence. The Indo-Iranians also borrowed their distinctive religious beliefs and practices from this culture.

The Indo-Iranian migrations took place in two waves. The first wave consisted of the Indo-Aryan migration into the Levant, founding the Mittani kingdom, and a migration south-eastward of the Vedic people, over the Hindu Kush into northern India. The Indo-Aryans split-off around 1800–1600 BC from the Iranians, where-after they were defeated and split into two groups by the Iranians, who dominated the Central Eurasian steppe zone and "chased [the Indo-Aryans] to the extremities of Central Eurasia." One group were the Indo-Aryans who founded the Mitanni kingdom in northern Syria; (c. 1500–1300 BC) the other group were the Vedic people. Christopher I. Beckwith suggests that the Wusun, an Indo-European Caucasian people of Inner Asia in antiquity, were also of Indo-Aryan origin.

The

second wave is interpreted as the Iranian wave, and took place in

the third stage of the Indo-European migrations from 800 BC onwards.

According to Allentoft (2015), the Sintashta culture probably derived from the Corded Ware culture The Sintashta culture, also known as the Sintashta-Petrovka culture or Sintashta-Arkaim culture, is a Bronze Age archaeological culture of the northern Eurasian steppe on the borders of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, dated to the period 2100–1800 BC. It is probably the archaeological manifestation of the Indo-Iranian language group.

The Sintashta culture emerged from the interaction of two antecedent cultures. Its immediate predecessor in the Ural-Tobol steppe was the Poltavka culture, an offshoot of the cattle-herding Yamnaya horizon that moved east into the region between 2800 and 2600 BC. Several Sintashta towns were built over older Poltavka settlements or close to Poltavka cemeteries, and Poltavka motifs are common on Sintashta pottery. Sintashta material culture also shows the influence of the late Abashevo culture, a collection of Corded Ware settlements in the forest steppe zone north of the Sintashta region that were also predominantly pastoralist. Allentoft et al. (2015) also found close autosomal genetic relationship between peoples of Corded Ware culture and Sintashta culture.

The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta burials, and the culture is considered a strong candidate for the origin of the technology, which spread throughout the Old World and played an important role in ancient warfare. Sintashta settlements are also remarkable for the intensity of copper mining and bronze metallurgy carried out there, which is unusual for a steppe culture.

Because of the difficulty of identifying the remains of Sintashta sites beneath those of later settlements, the culture was only recently distinguished from the Andronovo culture. It is now recognised as a separate entity forming part of the 'Andronovo horizon'.

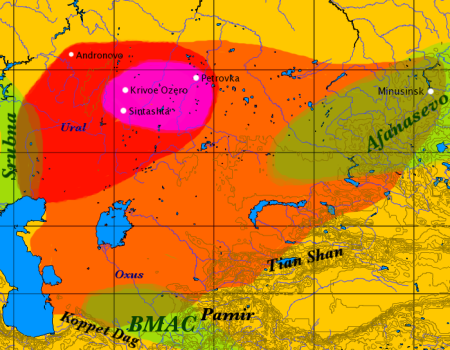

Andronovo culture :

The

Andronovo culture's approximate maximal extent, with the formative

Sintashta-Petrovka culture (red), the location of the earliest spoke-wheeled

chariot finds (purple), and the adjacent and overlapping Afanasevo,

Srubna, and BMAC cultures (green).

• Sintashta-Petrovka-Arkaim (Southern Urals, northern Kazakhstan, 2200–1600 BC)

The geographical extent of the culture is vast and difficult to delineate exactly. On its western fringes, it overlaps with the approximately contemporaneous, but distinct, Srubna culture in the Volga-Ural interfluvial. To the east, it reaches into the Minusinsk depression, with some sites as far west as the southern Ural Mountains, overlapping with the area of the earlier Afanasevo culture. Additional sites are scattered as far south as the Koppet Dag (Turkmenistan), the Pamir (Tajikistan) and the Tian Shan (Kyrgyzstan). The northern boundary vaguely corresponds to the beginning of the Taiga. In the Volga basin, interaction with the Srubna culture was the most intense and prolonged, and Federovo style pottery is found as far west as Volgograd.

Most researchers associate the Andronovo horizon with early Indo-Iranian languages, though it may have overlapped the early Uralic-speaking area at its northern fringe.

Scythians and Persians :

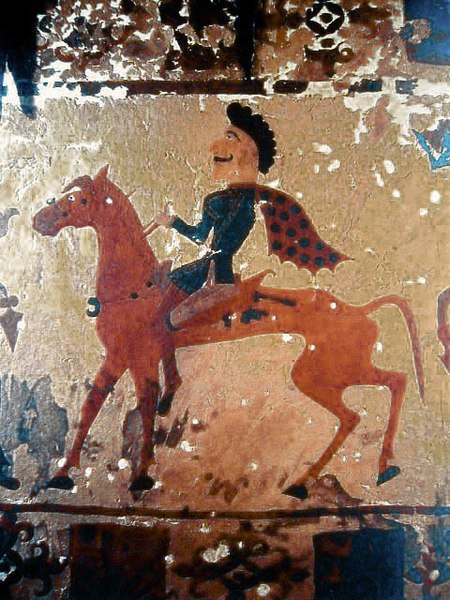

Scythian horseman, Pazyryk, from a carpet, c. 300 BC From the late 2nd millennium BC to early 1st millennium BC the Iranians had expanded from the Eurasian Steppe, and Iranian peoples such as Medes, Persians, Parthians and Bactrians populated the Iranian Plateau.

Scythian tribes, along with Cimmerians, Sarmatians and Alans populated the steppes north of the Black Sea. The Scythian and Sarmatian tribes were spread across Great Hungarian Plain, South-Eastern Ukraine, Russias Siberian, Southern, Volga, Uralic regions and the Balkans, while other Scythian tribes, such as the Saka, spread as far east as Xinjiang, China. Scythians as well formed the Indo-Scythian Empire, and Bactrians formed a Greco-Bactrian Kingdom founded by Diodotus I, the satrap of Bactria. The Kushan Empire, with Bactrian roots/connections, once controlled much of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. The Kushan elite (who the Chinese called the Yuezhi) were an Eastern Iranian language-speaking people.

Western

and Eastern Iranians :

Western Iranian peoples :

Extent of Iranian influence in the 1st century BC. The Parthian Empire (mostly Western Iranian) is shown in red, other areas, dominated by Scythia (Eastern Iranian), in orange

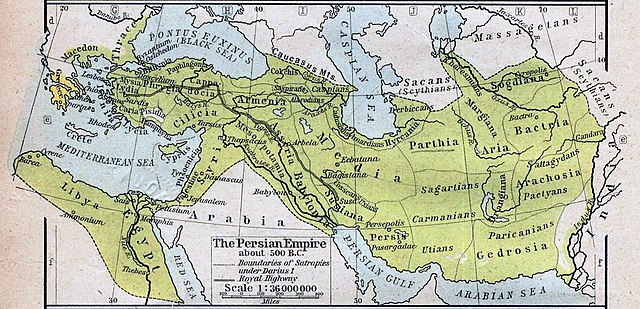

Achaemenid Empire at its greatest extent under the rule of Darius I (522 BC to 486 BC)

Distribution of modern Iranian languages

Persepolis : Persian guards During the 1st centuries of the 1st millennium BC, the ancient Persians established themselves in the western portion of the Iranian Plateau and appear to have interacted considerably with the Elamites and Babylonians, while the Medes also entered in contact with the Assyrians. Remnants of the Median language and Old Persian show their common Proto-Iranian roots, emphasized in Strabo and Herodotus' description of their languages as very similar to the languages spoken by the Bactrians and Sogdians in the east. Following the establishment of the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian language (referred to as "Farsi" in Persian) spread from Pars or Fars Province to various regions of the Empire, with the modern dialects of Iran, Afghanistan (also known as Dari) and Central-Asia (known as Tajiki) descending from Old Persian.

At first, the Western Iranian peoples in the Near East were dominated by the various Assyrian empires. An alliance of the Medes with the Persians, and rebelling Babylonians, Scythians, Chaldeans, and Cimmerians, helped the Medes to capture Nineveh in 612 BC, which resulted in the eventual collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire by 605 BC. The Medes were subsequently able to establish their Median kingdom (with Ecbatana as their royal centre) beyond their original homeland and had eventually a territory stretching roughly from northeastern Iran to the Halys River in Anatolia. After the fall of the Assyrian Empire, between 616 BC and 605 BC, a unified Median state was formed, which, together with Babylonia, Lydia, and Egypt, became one of the four major powers of the ancient Near East.

Later on, in 550 BC, Cyrus the Great, would overthrow the leading Median rule, and conquer Kingdom of Lydia and the Babylonian Empire after which he established the Achaemenid Empire (or the First Persian Empire), while his successors would dramatically extend its borders. At its greatest extent, the Achaemenid Empire would encompass swaths of territory across three continents, namely Europe, Africa and Asia, stretching from the Balkans and Eastern Europe proper in the west, to the Indus Valley in the east. The largest empire of ancient history, with their base in Persis (although the main capital was located in Babylon) the Achaemenids would rule much of the known ancient world for centuries.

This First Persian Empire was equally notable for its successful model of a centralised, bureaucratic administration (through satraps under a king) and a government working to the profit of its subjects, for building infrastructure such as a postal system and road systems and the use of an official language across its territories and a large professional army and civil services (inspiring similar systems in later empires), and for emancipation of slaves including the Jewish exiles in Babylon, and is noted in Western history as the antagonist of the Greek city states during the Greco-Persian Wars. The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was built in the empire as well.

The Greco-Persian Wars resulted in the Persians being forced to withdraw from their European territories, setting the direct further course of history of Greece and the rest of Europe. More than a century later, a prince of Macedon (which itself was a subject to Persia from the late 6th century BC up to the First Persian invasion of Greece) later known by the name of Alexander the Great, overthrew the incumbent Persian king, by which the Achaemenid Empire was ended.

Old Persian is attested in the Behistun Inscription (c. 519 BC), recording a proclamation by Darius the Great. In southwestern Iran, the Achaemenid kings usually wrote their inscriptions in trilingual form (Elamite, Babylonian and Old Persian) while elsewhere other languages were used. The administrative languages were Elamite in the early period, and later Imperial Aramaic, as well as Greek, making it a widely used bureaucratic language. Even though the Achaemenids had extensive contacts with the Greeks and vice versa, and had conquered many of the Greek-speaking area's both in Europe and Asia Minor during different periods of the empire, the native Old Iranian sources provide no indication of Greek linguistic evidence. However, there is plenty of evidence (in addition to the accounts of Herodotus) that Greeks, apart from being deployed and employed in the core regions of the empire, also evidently lived and worked in the heartland of the Achaemenid Empire, namely Iran. For example, Greeks were part of the various ethnicities that constructed Darius' palace in Susa, apart from the Greek inscriptions found nearby there, and one short Persepolis tablet written in Greek.

The early inhabitants of the Achaemenid Empire appear to have adopted the religion of Zoroastrianism. The Baloch who speak a west Iranian language relate an oral tradition regarding their migration from Aleppo, Syria around the year 1000 CE, whereas linguistic evidence links Balochi to Kurmanji, Soranî, Gorani and Zazaki language.

Eastern Iranian peoples :

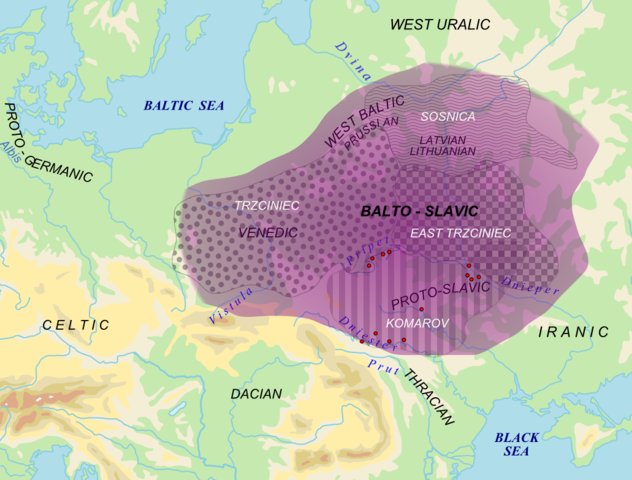

The Eastern Iranian and Balto-Slavic dialect continuums in Eastern Europe, the latter with proposed material cultures correlating to speakers of Balto-Slavic in the Bronze Age (white). Red dots = archaic Slavic hydronyms

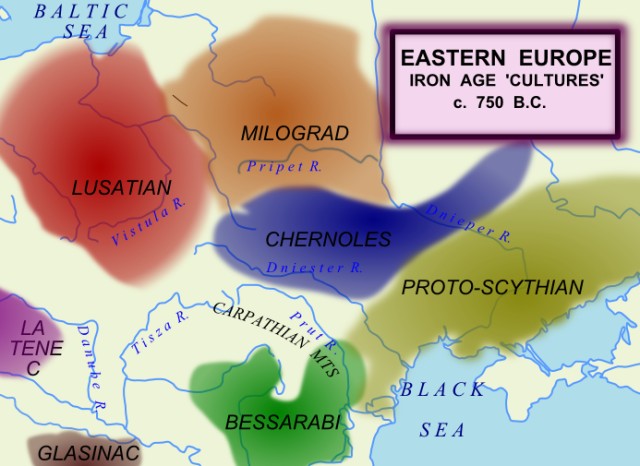

Archaeological cultures c. 750 BC at the start of Eastern-Central Europe's Iron Age; the Proto-Scythian culture borders the Balto-Slavic cultures (Lusatian, Milograd and Chernoles)

Silver

coin of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II (reigned c. 35–12 BC).

Buddhist triratna symbol in the left field on the reverse

It is believed that these Scythians were conquered by their eastern cousins, the Sarmatians, who are mentioned by Strabo as the dominant tribe which controlled the southern Russian steppe in the 1st millennium AD. These Sarmatians were also known to the Romans, who conquered the western tribes in the Balkans and sent Sarmatian conscripts, as part of Roman legions, as far west as Roman Britain. These Iranian-speaking Scythians and Sarmatians dominated large parts of Eastern Europe for a millennium, and were eventually absorbed and assimilated (e.g. Slavicisation) by the Proto-Slavic population of the region.

The Sarmatians differed from the Scythians in their veneration of the god of fire rather than god of nature, and women's prominent role in warfare, which possibly served as the inspiration for the Amazons. At their greatest reported extent, around the 1st century AD, these tribes ranged from the Vistula River to the mouth of the Danube and eastward to the Volga, bordering the shores of the Black and Caspian Seas as well as the Caucasus to the south. Their territory, which was known as Sarmatia to Greco-Roman ethnographers, corresponded to the western part of greater Scythia (mostly modern Ukraine and Southern Russia, also to a smaller extent north eastern Balkans around Moldova). According to authors Arrowsmith, Fellowes and Graves Hansard in their book A Grammar of Ancient Geography published in 1832, Sarmatia had two parts, Sarmatia Europea and Sarmatia Asiatica covering a combined area of 503,000 sq mi or 1,302,764 km2.

Throughout the 1st millennium CE, the large presence of the Sarmatians who once dominated Ukraine, Southern Russia, and swaths of the Carpathians, gradually started to diminish mainly due to assimilation and absorption by the Germanic Goths, especially from the areas near the Roman frontier, but only completely by the Proto-Slavic peoples. The abundant East Iranian-derived toponyms in Eastern Europe proper (e.g. some of the largest rivers; the Dniestr and Dniepr), as well as loanwords adopted predominantly through the Eastern Slavic languages and adopted aspects of Iranian culture amongst the early Slavs, are all a remnant of this. A connection between Proto-Slavonic and Iranian languages is also furthermore proven by the earliest layer of loanwords in the former. For instance, the Proto-Slavonic words for god (*bog?), demon (*div?), house (*xata), axe (*topor?) and dog (*sobaka) are of Scythian origin.

The extensive contact between these Scytho-Sarmatian Iranian tribes in Eastern Europe and the (Early) Slavs included religion. After Slavic and Baltic languages diverged the Early Slavs interacted with Iranian peoples and merged elements of Iranian spirituality into their beliefs. For example, both Early Iranian and Slavic supreme gods were considered givers of wealth, unlike the supreme thunder gods in many other European religions. Also, both Slavs and Iranians had demons –- given names from similar linguistic roots, Daêva (Iranian) and Divu (Slavic) –- and a concept of dualism, of good and evil.The Sarmatians of the east, based in the Pontic–Caspian steppe, became the Alans, who also ventured far and wide, with a branch ending up in Western Europe and then North Africa, as they accompanied the Germanic Vandals and Suebi during their migrations. The modern Ossetians are believed to be the direct descendants of the Alans, as other remnants of the Alans disappeared following Germanic, Hunnic and ultimately Slavic migrations and invasions. Another group of Alans allied with Goths to defeat the Romans and ultimately settled in what is now called Catalonia (Goth-Alania).

Hormizd I, Sassanian coin Some of the Saka-Scythian tribes in Central Asia would later move further southeast and invade the Iranian Plateau, large sections of present-day Afghanistan and finally deep into present day Pakistan. Another Iranian tribe related to the Saka-Scythians were the Parni in Central Asia, and who later become indistinguishable from the Parthians, speakers of a northwest-Iranian language. Many Iranian tribes, including the Khwarazmians, Massagetae and Sogdians, were assimilated and/or displaced in Central Asia by the migrations of Turkic tribes emanating out of Xinjiang and Siberia.

The modern Sarikoli in southern Xinjiang and the Ossetians of the Caucasus (mainly South Ossetia and North Ossetia) are remnants of the various Scythian-derived tribes from the vast far and wide territory they once dwelled in. The modern Ossetians are the descendants of the Alano-Sarmatians, and their claims are supported by their Northeast Iranian language, while culturally the Ossetians resemble their North Caucasian neighbors, the Kabardians and Circassians. Various extinct Iranian peoples existed in the eastern Caucasus, including the Azaris, while some Iranian peoples remain in the region, including the Talysh and the Tats (including the Judeo-Tats, who have relocated to Israel), found in Azerbaijan and as far north as the Russian republic of Dagestan. A remnant of the Sogdians is found in the Yaghnobi-speaking population in parts of the Zeravshan valley in Tajikistan.

Later

developments :

Later, during the 2nd millennium AD, the Iranian peoples would play a prominent role during the age of Islamic expansion and empire. Saladin, a noted adversary of the Crusaders, was an ethnic Kurd, while various empires centered in Iran (including the Safavids) re-established a modern dialect of Persian as the official language spoken throughout much of what is today Iran and the Caucasus. Iranian influence spread to the neighbouring Ottoman Empire, where Persian was often spoken at court (though a heavy Turko-Persian basis there was set already by the predecessors of the Ottomans in Anatolia, namely the Seljuks and the Sultanate of Rum amongst others) as well to the court of the Mughal Empire. All of the major Iranian peoples reasserted their use of Iranian languages following the decline of Arab rule, but would not begin to form modern national identities until the 19th and early 20th centuries (just as many European communities, such as Germany and Italy, began to formulate national identities of their own).

Demographics

:

Due to recent migrations, there are also large communities of speakers of Iranian languages in Europe, the Americas, and Israel.

List of Iranian peoples with the respective groups's core areas of settlements and their estimated sizes :

Culture :

Nowruz, an ancient Iranian annual festival that is still widely celebrated throughout the Iranian Plateau and beyond, in Dushanbe, Tajikistan Iranian culture is today considered to be centered in what is called the Iranian Plateau, and has its origins tracing back to the Andronovo culture of the late Bronze Age, which is associated with other cultures of the Eurasian Steppe. It was, however, later developed distinguishably from its earlier generations in the Steppe, where a large number of Iranian-speaking peoples (i.e., the Scythians) continued to participate, resulting in a differentiation that is displayed in Iranian mythology as the contrast between Iran and Turan.

Like other Indo-Europeans, the early Iranians practiced ritual sacrifice, had a social hierarchy consisting of warriors, clerics, and farmers, and recounted their deeds through poetic hymns and sagas. Various common traits can be discerned among the Iranian peoples. For instance, the social event of Nowruz is an ancient Iranian festival that is still celebrated by nearly all of the Iranian peoples. However, due to their different environmental adaptations through migration, the Iranian peoples embrace some degrees of diversity in dialect, social system, and other aspects of culture.

With numerous artistic, scientific, architectural, and philosophical achievements and numerous kingdoms and empires that bridged much of the civilized world in antiquity, the Iranian peoples were often in close contact with people from various western and eastern parts of the world.

Religion :

The ruins at Kangavar, Iran, presumed to belong to a temple dedicated to the ancient goddess Anahita The early Iranian peoples practiced the ancient Iranian religion, which, like that of other Indo-European peoples, embraced various male and female deities. Fire was regarded as an important and highly sacred element, and also a deity. In ancient Iran, fire was kept with great care in fire temples. Various annual festivals that were mainly related to agriculture and herding were celebrated, the most important of which was the New Year (Nowruz), which is still widely celebrated. Zoroastrianism, a form of the ancient Iranian religion that is still practiced by some communities, was later developed and spread to nearly all of the Iranian peoples living in the Iranian Plateau. Other religions that had their origins in the Iranian world were Mithraism, Manichaeism, and Mazdakism, among others. The various religions of the Iranian peoples are believed by some scholars to have been significant early philosophical influences on Christianity and Judaism.

Cultural assimilation :

A caftan worn by a Sogdian horseman, 8th–10th century Iranian languages were and, to a lesser extent, still are spoken in a wide area comprising regions around the Black Sea, the Caucasus, Central Asia, Russia and the northwest of China. This population was linguistically assimilated by smaller but dominant Turkic-speaking groups, while the sedentary population eventually adopted the Persian language, which began to spread within the region since the time of the Sasanian Empire. The language-shift from Middle Iranian to Turkic and New Persian was predominantly the result of an "elite dominance" process. Moreover, various Turkic-speaking ethnic groups of the Iranian Plateau are often conversant also in an Iranian language and embrace Iranian culture to the extent that the term Turko-Iranian would be applied. A number of Iranian peoples were also intermixed with the Slavs, and many were subjected to Slavicisation.

The following either partially descend from or are sometimes regarded as descendants of the Iranian peoples :

•

Turkic-speakers

• Azerbaijanis : In spite of being native speakers of a Turkic language (Azerbaijani Turkic), they are believed to be primarily descended from the earlier Iranian-speakers of the region. They are possibly related to the ancient Iranian tribe of the Medes, aside from the rise of the subsequent Persian and Turkic elements within their area of settlement, which, prior to the spread of Turkic, was Iranian-speaking. Thus, due to their historical, genetic and cultural ties to the Iranians, the Azerbaijanis are often associated with the Iranian peoples. Genetic studies observed that they are also genetically related to the Iranian peoples. • Turkmens : Genetic studies show that the Turkmens are characterized by the presence of local Iranian mtDNA lineages, similar to the eastern Iranian populations, but modest female Mongoloid mtDNA components were observed in Turkmen populations with the frequencies of about 20%. • Uzbeks : The unique grammatical and phonetical features of the Uzbek language, as well as elements within the modern Uzbek culture, reflect the older Iranian roots of the Uzbek people. According to recent genetic genealogy testing from a University of Oxford study, the genetic admixture of the Uzbeks clusters somewhere between the Iranian peoples and the Mongols. Prior to the Russian conquest of Central Asia, the local ancestors of the Turkic-speaking Uzbeks and the Iranian-speaking Tajiks, both living in Central Asia, were referred to as Sarts, while Uzbek and Turk were the names given to the nomadic and semi-nomadic populations of the area. Still, as of today, modern Uzbeks and Tajiks are known to their Turkic neighbors, the Kazakhs and the Kyrgyz, as Sarts. Some Uzbek scholars also favor the Iranian origin theory. [page needed] • Uyghurs : Contemporary scholars consider modern Uyghurs to be the descendants of, apart from the ancient Uyghurs, the Iranian Saka (Schytian) tribes and other Indo-European peoples who inhabited the Tarim Basin before the arrival of the Turkic tribes. • Slavic-speakers • Swahili-speakers • Shirazis : The Shirazi are a sub-group of the Swahili people living on the Swahili coast of East Africa, especially on the islands of Zanzibar, Pemba, and Comoros. Local traditions about their origin claim they are descended from merchant princes from Shiraz in Iran who settled along the Swahili coast.

Genetics :

A Tajik woman holding her child

Three Kurdish children from Bismil Province, Turkey Regueiro et al (2006) and Grugni et al (2012) have performed large-scale sampling of different ethnic groups within Iran. They found that the most common Haplogroups were :

• J1-M267 : Typical of Semitic-speaking

people, was rarely over 10% in Iranian groups.

•

R1a (subclade not further analyzed) was the predominant haplogroup,

especially amongst Pashtuns, Balochi and Tajiks.

Overall in Iran, native population groups do not form tight clusters either according to language or region. Rather, they occupy intermediate positions among Near Eastern and Caucasus clusters. Some of the Iranian groups lie within the Near Eastern group (often with such as the Turks), but none fell into the Arab or Asian groups. Some Iranian groups in Iran, such as the Gilakis and Mazandaranis, have paternal genetics (Y-DNA) virtually identical to South Caucasus ethnic groups.

Iranians are only distantly related to Europeans as a whole, predominantly with Southern Europeans like Greeks, Albanians, Serbs, Croatians, Italians, Bosniaks, Spaniards, Macedonians, Portuguese, and Bulgarians, rather than northern Europeans like Norwegians, Danes, Swedes, Irish, Scottish, Welsh, English, Finns, Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians. Nevertheless, Iranian-speaking Central Asians do show closer affinity to Europeans than do Turkic-speaking Central Asians.

A study with 1021 samples from eleven ethnic groups by Merjoo and her colleagues shows that most of ethnic groups in Iran including Iranian Arabs, Azeris, Gilaks, Kurds, Mazanderanis, Lurs and Persians can be regarded as one heterogeneous cluster. While Baluchs, Sistanis, Turkmans and Southern Islanders are admixture groups. The comparison between main genetic cluster of Iran with the ancient cases shows continuity for at least 5000 years and just migration of Caucasus populations during Neolithic through Bronze Age times.

Source :

https://en.wikipedia.org |

.jpg)